The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Barbara

In the main passenger terminal, chaos predominated.

Arthur Hailey

Prologue

Any technology gradually creates a totally new human environment.

Marshall McLuhan

It was my cousins last day in the United StatesAugust 26, 1964and he wanted to see the worlds fair before flying back to London. My father drove us in his Buick to Flushing Meadow. The sky over Long Island was tempered blue and streaked with contrails. We bought tickets for General Motorss Futurama exhibit and rode around a miniature landscape that showed what life would be like in the future. My cousin and I were disappointed. There was something hokey about the whole fair, and the so-called future seemed shabby.

We then drove south a few miles on the Van Wyck Expressway and reached the periphery of Idlewild, which is what my father still called the airport, although it had been renamed John F. Kennedy International the year before. We glided along freshly paved overpasses and beneath the signs bearing candy-colored numbers. The terminals were strung out like pavilions around the looping roadway, and it felt as if we were back at the fair. There was the flashy stained-glass entry to American Airlines, the flying-saucer roof of Pan Am, and the endless glass facade of the arrivals building. Then we parked in front of the TWA terminal and walked inside.

I had seen photographs of the birdlike structure, but none had done it justice. The interior was a continuously flowing surface of cast concrete. There were no sharp corners, no right angles, no dull flat ceilings. The building was topsy-turvyin some places the walls swooped down to become floor, while other parts curved above our heads like ocean waves that were about to break yet were somehow frozen in place. Between the vaults were gaping ellipses of glass through which you might see a tail fin or a passing cloud. I was only twelve and knew nothing about architecture, but the pavilions at the worlds fair seemed stodgy in comparison. This wasnt pretending to be the future; this was the future. Those were real Boeing 707s sitting on the tarmac.

The air was charged with anticipation. Pilots stepped through pools of milky light. Beautiful stewardesses trailed behind them wearing trim red outfits and perfectly straight stocking seams. The ambient lighting, the flirtatious smiles, the lipstick-red carpet and uniforms, the cushioned benches and steel railings curving around the mezzanineall conspired on the senses. Even the clock that hung from the ceiling had a suggestive globular shape. We sat in an oversize conversation pit, beneath a panoramic screen of glass, and watched the service vehicles scoot between the planes. This is unbelievably cool, said my cousin in a hushed, almost reverential tone.

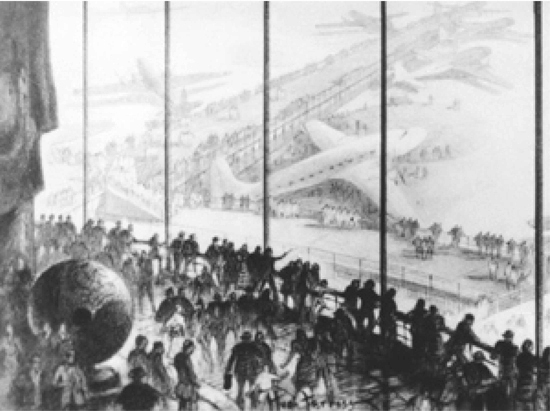

When his flight was announced, he walked up the long umbilical departure tube, turned once to wave, like an astronaut, and then disappeared into the satellite at the far end of the tube. There was an otherworldly, Twilight Zone quality to this momentas if my cousin were flying not to London but to Mars. Perhaps it was the recessed lighting or the curved walls that made for the slow-motion, spacy feeling. Perhaps it was the subtle rise of floor that made the boarding tube seem hyperextended, much longer than it actually was. All I knew was that I didnt want to leave just then. I wanted to savor the moment.

Still, my father and I headed back onto the Belt Parkway and drove east into the slanting afternoon light. I was unsettled for the rest of the drive: my cousins departure had been dreamlike and elusive but, at the same time, very realthe essential modern momentwhen technology seemed perfectly in tune with human aspiration, before hijackings and air rage, before jumbo jets, before deregulation, dysfunctional baggage carousels, and electromagnetic scanners.

Departure tube at the TWA terminal, Idlewild/Kennedy Airport, circa 1962.

Over the next few years I flew frequently but never on TWA until I took a student year abroad. My flight had been booked on another airline, but it was canceled because of a bomb threat at JFK. It was Black September, 1970. There were bombs going off everywhere. The only available flight to Paris was on TWA, and I was able to transfer my ticket, pleased to get the chance to return to that inspiring terminal and walk up its mysterious boarding tube.

I pushed my way through a mob of angry German touriststheir flight had been canceled as welland noticed how some of the openings had been boarded over with ugly sheets of plywood. The glacial panes of glass were grimy. The too-bright lighting cast garish shadows on the concrete walls that now looked cracked and drythe texture of old chewing gum. The bright red carpeting was now faded and curling at the edges. The stewardesses looked haggard.

My plane was almost empty except for a group of plucky dames from Dallas who were heading to Paris on a shopping spree and werent going to let any terrorists ruin their fun. Drinks were free, and when the plane touched down at Charles de Gaulle, everyone stood and cheered. My next few flights across the Atlantic were on cheap charter planes, and I learned to lower my expectations. Air travel had become an ordeal to be endured, not enjoyed. But I always wondered what had happened in that brief interval between the perfect airport moment of 1964 and the disappointments of later years.

As air travelers, we remove ourselves from the experience by thinking about something else, but we are never altogether comfortable with the airport process. Instead of being thrilledas I was at twelvewe are more often than not horrified or bored by the reality. We check our bags and pass through security. We stand on the moving sidewalk and learn the status of our flight from a computer screen. We are both repelled and attracted at the same time. Some react with air rage, incensed by the impersonal nature of the setting. Others feel oddly light-headed, disembodied, or experience, as Joan Didion once wrote, a certain weightlessness. Most of us just want to reach our destination as quickly and safely as possible.

A sign at an airport construction site today reads: EXCUSE OUR APPEARANCES. WE ARE TEARING DOWN YESTERDAY TO MAKE ROOM FOR TOMORROW . But the idealized tomorrow never comes. The airport is at once a place, a system, a cultural artifact that brings us face-to-face with the advantages as well as the frustrations of modernity. The sprawling, hybrid nature of the subject challenges easy assumptions. Its history has been a recurrent cycle of anticipation and disappointment, success and failure, innovation and obsolescence. This book traces that history through mutations of technology, design, and marketingshowing how the airport was gradually shaped into a new kind of human environment, while, in turn, shaping the rest of the modern world.