Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

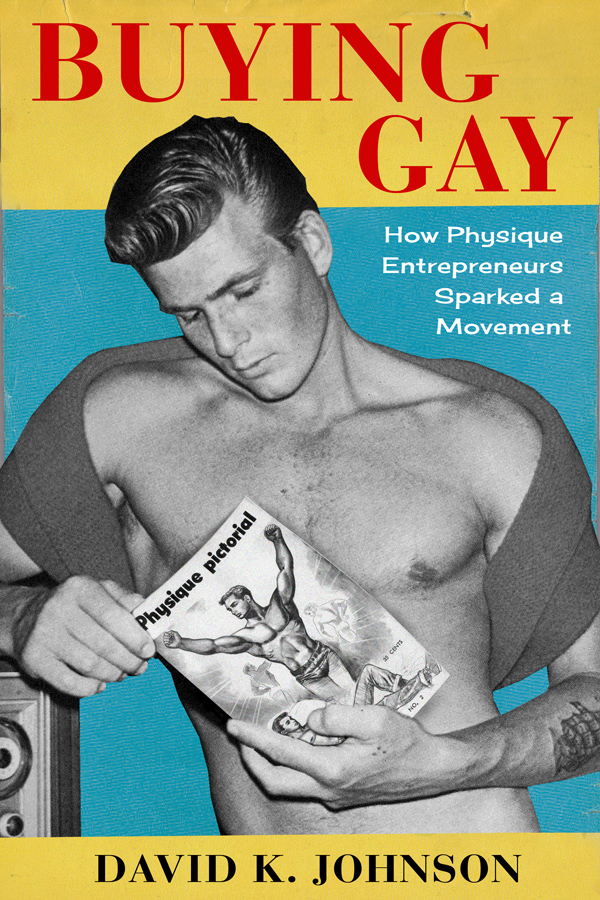

BUYING GAY

COLUMBIA STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF U.S. CAPITALISM

COLUMBIA STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF U.S. CAPITALISM

Series Editors: Devin Fergus, Louis Hyman, Bethany Moreton, and Julia Ott

Capitalism has served as an engine of growth, a source of inequality, and a catalyst for conflict in American history. While remaking our material world, capitalisms myriad forms have alteredand been shaped byour most fundamental experiences of race, gender, sexuality, nation, and citizenship. This series takes the full measure of the complexity and significance of capitalism, placing it squarely back at the center of the American experience. By drawing insight and inspiration from a range of disciplines and alloying novel methods of social and cultural analysis with the traditions of labor and business history, our authors take history from the bottom up all the way to the top.

Capital of Capital: Money, Banking, and Power in New York City, 17842012 , by Steven H. Jaffe and Jessica Lautin

From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs , by Joshua Clark Davis

Creditworthy: A History of Consumer Surveillance and Financial Identity in America , by Josh Lauer

American Capitalism: New Histories , by Sven Beckert and Christine Desan, editors

BUYING GAY

How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement

DAVID K. JOHNSON

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54817-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Johnson, David K., author.

Title: Buying gay : how physique entrepreneurs sparked a movement / David K. Johnson.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2019] | Series: Columbia studies in the history of U.S. capitalism | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018033079 (print) | LCCN 2018037924 (ebook) |ISBN 9780231189101 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Gay menUnited StatesHistory. | Gay eroticaUnited StatesHistory. | BodybuildingPeriodicalsUnited StatesHistory. | Gay consumersUnited StatesHistory. | Gay business enterprisesUnited StatesHistory. | Gay rightsUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC HQ76.3.U5 (ebook) | LCC HQ76.3.U5 J583 2019 (print) | DDC 306.76/620973--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018033079

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

CONTENTS

I first discovered physique magazines in the attic of a gay rights activist from the 1960s. While perusing yellowing government documents and organizational meeting minutes on fading onion-skin paper, my eyes were drawn to copies of magazines called Drum , Physique Pictorial , and MANual full of images of nearly naked men.

While they were more attractive than the dull, typewritten correspondence in the adjacent files, I felt guilty for being distracted from what I thought to be my real goaldocumenting the important struggle between the federal government and gay men and lesbians in 1950s and 1960s America. After all, I was researching a book on the federal governments Cold War purge of suspected homosexuals as threats to national securityhow we were allegedly part of a communist conspiracy to take over American societyand how gay activists had organized to protest such discriminatory policies. These physique magazines, I told myself, were fluff, to be enjoyed after the work was done. It was the 1990s, and I accepted the historical professions and societys definition of what is of historic importance and what is pornography, of what is political and what is commercial entertainment. But I have come back now to give them a second look and see how they might change our understanding of that history. And I am not alone in that search.

Soon after my discovery, physique photography was enjoying a veritable renaissance outside the academy as art galleries and museums hosted retrospective exhibitions I saw a puzzling disconnect between popular appreciation for these physique pioneers and academic dismissal, if not outright distain. I began to wonder why historians of the LGBT community had minimized their significance.

As early as 1982 Dennis Altman alerted us to the central role that commercial enterprises have played in the development of gay community. One of the ironies of American capitalism, he wrote, is that it has been a major force in creating and maintaining a sense of identity among homosexuals. Writing about the same time, John DEmilio also stressed how the development of urban wage labor capitalism opened a space for men and women attracted to members of their own sex to find one another and forge community. Neither historians who stressed the role of bars nor those who focused on political organizing gave the realm of consumer culture more than a cursory glance.

One explanation for this oversight is the difficulty in finding sources. While the papers of homophile organizations have been carefully preserved and cataloged, the ephemera of commercial enterprises has tended to disappear. Only recently have academic and community-based libraries begun to collect these materials.

As a result, most scholars and activists who have investigated a gay market position it as a post-Stonewall development. Imagining capitalism and activism as antithetical, they see a process of selling out, a narrative in which a leftist political movement has declined into a market niche, a corporatized arm of the neoliberal establishment.

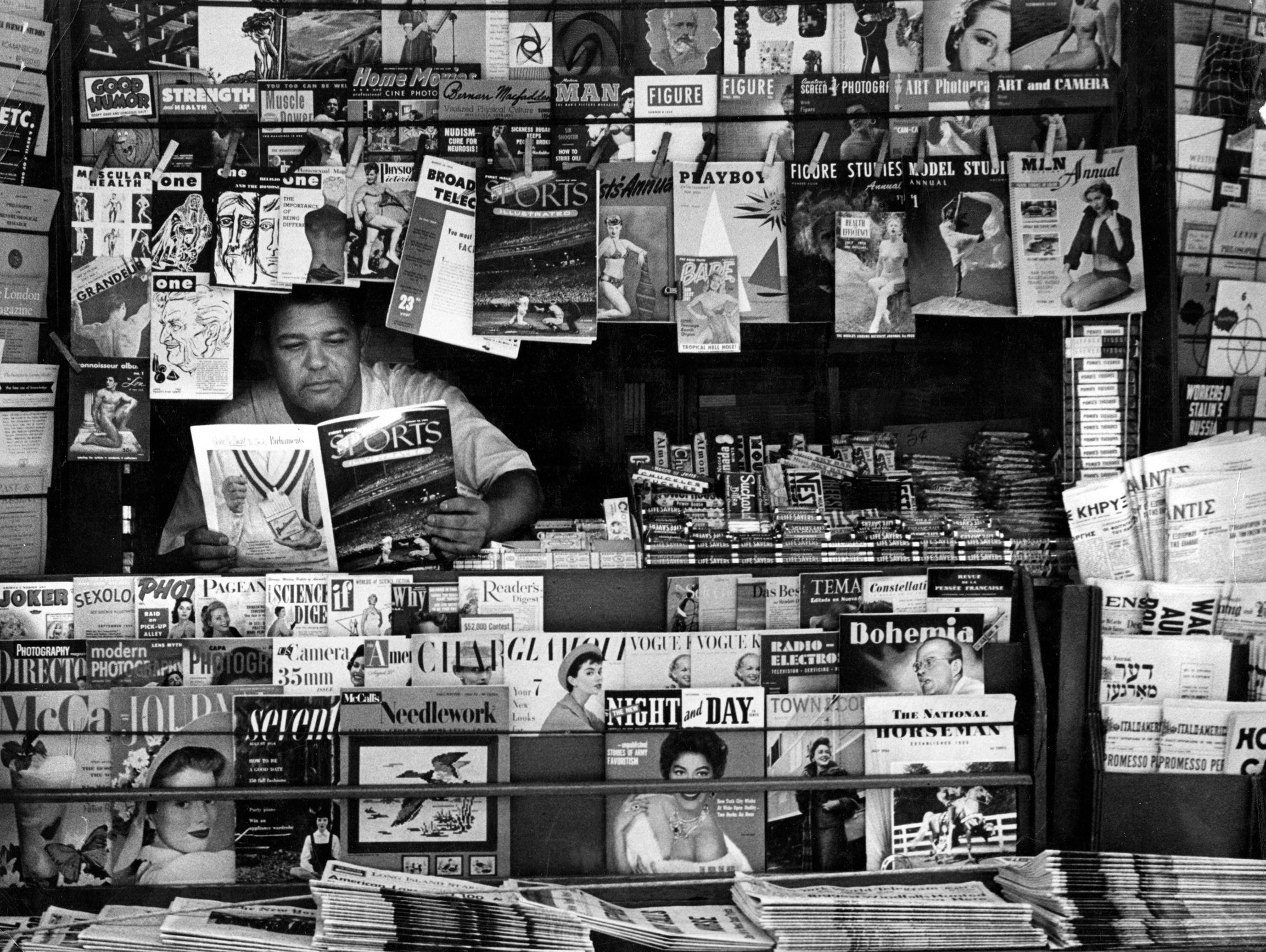

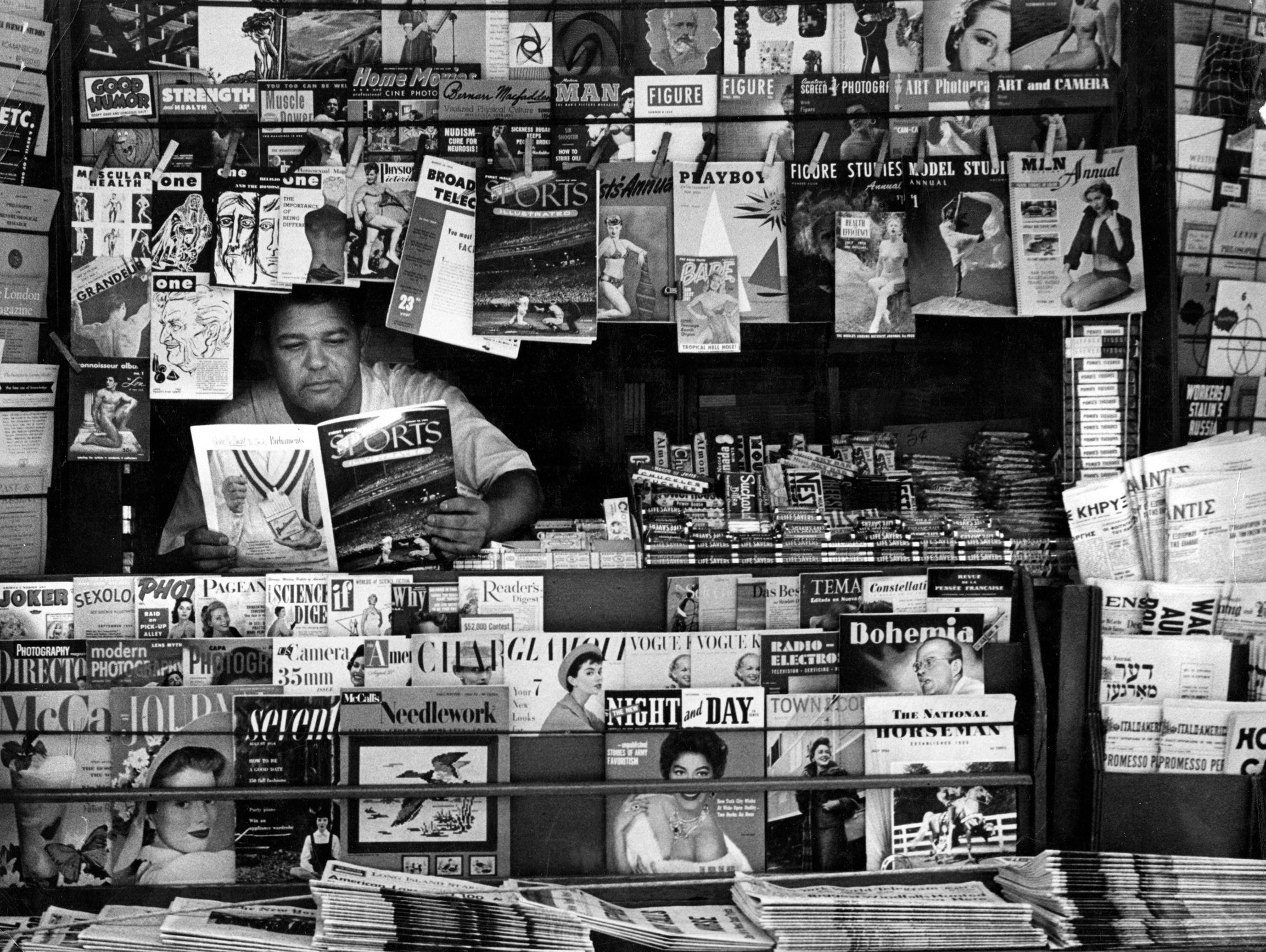

But what I found as I traveled around the country researching was that the notion of a gay market was already enjoying wide currency nearly a decade before Stonewall. It was most clearly visible on the nations newsstands. A social scientist who examined the largest newsstand in Dayton, Ohio, in 1964 found twenty-five magazines targeting a gay audienceso many that the salesperson had established a special section for what he called his homosexual magazines. He mixed the magazines of the homophile political organizations, ONE and Mattachine Review , with the far larger cache of physiques.

Editors of tabloid and mainstream magazines realized the extent of this market whenever they published an article on homosexuality and saw their sales soar.

The most visible site of a gay market in the 1950s was the nations newsstands. This Times Square news seller established a homosexual section in the upper left corner just above his head to display both physique and homophile publications. He is reading the first issue of Sports Illustrated , December 1957.

Courtesy of Getty Images.

Its a movement, not a market

Further research in memoirs, letters, and novels demonstrates that the taking, exchanging, displaying, and viewing of physique photography and drawings have been central to gay male cultural life. Collecting and displaying these items formed a key element of gay mens sense of identity and served as ways to mark oneself as gay and signal this to others. Victor Banis wrote in 1963 about a gay bar where the photos pinned to the wall, pictures of nearly nude young men, mostly bodybuilders, identified the bar for what it was, a gay hangout. Gay men placing classified advertisements in mainstream periodicals would note their interest in physiques to signal their sexual interest in other men. Most fictional representations of the gay world in the pre-Stonewall era made frequent reference to physique photos or paintings. Fritz Peterss novel Finistere (1951), the coming-out story of Michael, a teenage boy at a French boarding school, offers a glimpse inside the apartment of a gay man whom Michael encountered on the streets of Paris. What set the space apart and marked it as gay was the artwork above the couch: All photographs, and all of men. Some of them had obviously been cut out of physical culture magazines, others were snapshots, mostly of men in bathing suits, in one or two cases entirely nude.