I. Introduction

It is rare to get through this life without feeling generally with a degree of secret agony, perhaps at the end of a relationship, or as we lie in bed frustrated next to our partner, unable to go to sleep that we are somehow a bit odd about sex. It is an area in which most of us have a painful impression, in our heart of hearts, that we are quite unusual. Despite being one of the most private of activities, sex is nonetheless surrounded by a range of powerful socially sanctioned ideas that codify how normal people are meant to feel about and deal with the matter.

In truth, however, few of us are remotely normal sexually. We are almost all haunted by guilt and neuroses, by phobias and disruptive desires, by indifference and disgust. None of us approaches sex as we are meant to, with the cheerful, sporting, non-obsessive, constant, well-adjusted outlook that we torture ourselves by believing that other people are endowed with. We are universally deviant but only in relation to some highly distorted ideals of normality.

Given how common it is to be strange, it is regrettable how seldom the realities of sexual life make it into the public realm. Most of what we are sexually remains impossible to communicate with anyone whom we would want to think well of us. Men and women in love will instinctively hold back from sharing more than a fraction of their desires out of a fear, usually accurate, of generating intolerable disgust in their partners. We may find it easier to die without having had certain conversations.

The priority of a philosophical book about sex seems evident: not to teach us how to have more intense or more frequent sex, but rather to suggest how, through a shared language, we might begin to feel a little less painfully strange about the sex we are either longing to have or struggling to avoid.

Whatever discomfort we do feel around sex is commonly aggravated by the idea that we belong to a liberated age and ought by now, as a result, to be finding sex a straightforward and untroubling matter.

The standard narrative of our release from our shackles goes something like this: for thousands of years across the globe, due to a devilish combination of religious bigotry and pedantic social custom, people were afflicted by a gratuitous sense of confusion and guilt around sex. They thought their hands would fall off if they masturbated. They believed they might be burned in a vat of oil because they had ogled someones ankle. They had no clue about erections or clitorises. They were ridiculous.

Then, sometime between the First World War and the launch of Sputnik 1, things changed for the better. Finally, people started wearing bikinis, admitted to masturbating, grew able to mention cunnilingus in social contexts, started to watch porn films and became deeply comfortable with a topic that had, almost unaccountably, been the source of needless neurotic frustration for most of human history. Being able to enter into sexual relations with confidence and joy became as common an expectation for the modern era as feeling trepidation and guilt had been for previous ages. Sex came to be perceived as a useful, refreshing and physically reviving pastime, a little like tennis something that everyone should have as often as possible in order to relieve the stresses of modern life.

This narrative of enlightenment and progress, however flattering it may be to our powers of reason and our pagan sensibilities, conveniently skirts an unbudging fact: sex is not something that we can ever expect to feel easily liberated from. It was not by mere coincidence that sex so disturbed us for thousands of years: repressive religious dictates and social taboos grew out of aspects of our nature that cannot now just be wished away. We were bothered by sex because it is a fundamentally disruptive, overwhelming and demented force, strongly at odds with the majority of our ambitions and all but incapable of being discreetly integrated within civilized society.

Despite our best efforts to clean it of its peculiarities, sex will never be either simple or nice in the ways we might like it to be. It is not fundamentally democratic or kind; it is bound up with cruelty, transgression and the desire for subjugation and humiliation. It refuses to sit neatly on top of love, as it should. Tame it though we may try, sex has a recurring tendency to wreak havoc across our lives: it leads us to destroy our relationships, threatens our productivity and compels us to stay up too late in nightclubs talking to people whom we dont like but whose exposed midriffs we nevertheless strongly wish to touch. Sex remains in absurd, and perhaps irreconcilable, conflict with some of our highest commitments and values. Unsurprisingly, we have no option but to repress its demands most of the time. We should accept that sex is inherently rather weird instead of blaming ourselves for not responding in more normal ways to its confusing impulses.

This is not to say that we cannot take steps to grow wiser about sex. We should simply realize that we will never entirely surmount the difficulties it throws our way. Our best hope should be for a respectful accommodation with an anarchic and reckless power.

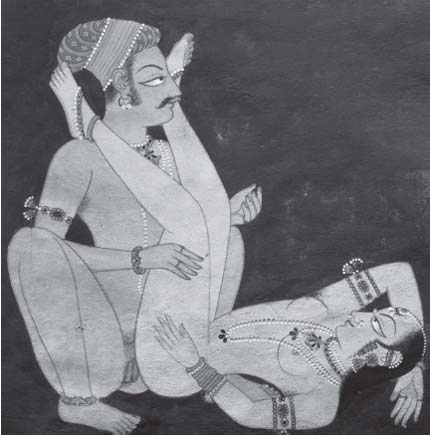

Sex manuals, ranging from the Kama Sutra to The Joy of Sex, have been united in locating the problems of sexuality in the physical sphere. Sex will go better they variously assure us when we master the lotus position, learn to use ice cubes creatively or apply proven techniques for attaining synchronized orgasm.

If we occasionally bristle at such manuals, it may be because beneath their encouraging prose and helpful diagrams they seem intolerably humiliating. They want us to take seriously the notion that sex is troublesome to us chiefly because we havent tried postillionage or got the hang of the Karezza method. Yet these are adventures at the luxurious end of the spectrum of human sexuality and mock the sorts of challenges we are more normally faced with.

For the majority of us, the real cause for concern is not how to make sex even more enjoyable with a lover who is already keen to spend several hours on a divan with us trying out new positions, amid the smell of jasmine and the song of hummingbirds. Rather, we worry about how problematic sex has become with our long-term partner due to mutual resentments over childcare and finances; or about our addiction to internet pornography; or about the fact that we seem to crave sex only with people we dont love; or about whether, by having had an affair with someone at work, we have irretrievably broken our spouses heart and trust.

The most urgent problems we face with sex seldom have anything to do with technique. Kama Sutra, India, late eighteenth century.

In the face of these problems and many more, we might question our expectations of how often we can rightly look forward to sex going well for us and, contrary to the spirit of the age, might conclude that a handful of occasions in a lifetime may be a fair and natural limit to our ambitions. Great sex, like happiness more generally, may be the precious and sublime exception.

During our most fortunate encounters, it is rare for us to appreciate how privileged we are. It is only as we get older, and look back repeatedly and nostalgically to a few erotic episodes, that we start to realize with what stinginess nature extends her gifts to us and therefore what an extraordinary and rare achievement of biology, psychology and timing satisfying sex really is.

Next page