The Concise Book of Muscles

Third Edition

Chris Jarmey and John Sharkey

Chichester, England

North Atlantic Books Berkeley, California Copyright 2003, 2008 by Chris Jarmey, and this third edition in 2015, copyright by Chris Jarmey and John Sharkey. All rights reserved. No portion of this book, except for brief review, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the written permission of the publisher. For information, contact Lotus Publishing or North Atlantic Books. First published in 2003, the second edition published in 2008, and this third edition published in 2015 by

Lotus Publishing Apple Tree Cottage, Inlands Road, Nutbourne, Chichester, PO18 8RJ and

North Atlantic Books Berkeley, California

Anatomical Drawings Amanda Williams

Exercise Drawings Matt Lambert

Cover Design Jasmine Hromjak

The Concise Book of Muscles, Third Edition is sponsored and published by the Society for the Study of Native Arts and Sciences (dba North Atlantic Books), an educational nonprofit based in Berkeley, California, that collaborates with partners to develop cross-cultural perspectives, nurture holistic views of art, science, the humanities, and healing, and seed personal and global transformation by publishing work on the relationship of body, spirit, and nature. North Atlantic Books publications are available through most bookstores.

For further information, visit our website at www.northatlanticbooks.com or call 800-733-3000. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 905367 62 7 (Lotus Publishing) ISBN 978 1 62317 020 2 (North Atlantic Books) The Library of Congress has cataloged the first edition as follows: Jarmey, Chris. The concise book of muscles/Chris Jarmey. p. ; cm. Includes . Includes .

ISBN 1-55643-466-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Muscles--Handbooks, manuals, etc. [DNLM: 1. 2. 2.

Muscles--innervation--Handbooks. 3. Anatomy, Regional--Atlases. 4. Anatomy, Regional--Handbooks. 5.

Muscles--anatomy & histology- Atlases. 6. Muscles--anatomy & histology--Handbooks. WE 17 J37c 2003] I. Title. QP321.J43 2003 612.74--dc21 2002155580

Contents

I was very honored to be tasked with preparing the third edition of

The Concise Book of Muscles, building on the excellent work that Chris Jarmey produced in the previous two editions.

Much has changed since the second edition, but I have endeavored to keep to the concise and easy-reference format that has made this text such a popular resource. Of course, time moves on and little stays the samethis is true of all things, including anatomy. Time gives birth to new facts, models, and hypotheses worthy of consideration and finally acceptance. New research has emerged on the topic of fascia and living motion, with the expression of new theories on myofascial force transmission and the continuity of our living architecture. While not throwing the baby out with the bathwater, my intention is that this latest edition should be seen as a product of a new understanding of the role of muscles and fascia (or, more correctly, connective tissue) in both force transmission and human movement (or living movement). To fully understand and appreciate the new and persuasive model of biotensegrity based on muscle synergies and four-bar closed kinematics, we must first be familiar with the fallacy of the old model of origin and insertiontwo-bar pin joints and external forcesthat underpins modern biomechanics.

In order to understand the present and the future, we must understand the past. Today, the study of anatomy is based on a tradition that is hundreds of years old; anatomy was a reflection of the vision and beliefs of those early anatomists. Many names given to muscles bore little or no relation to their functions, but reflected more what the anatomist saw: muscles were therefore named maximus or minimus, longus or brevis, anterior or posterior, etc. Even the word muscle originates from Latin musculus, meaning little mouse. As a clinical anatomist I cherish the history of anatomy and particularly the history which led to the anatomical naming of tissues, organs, muscles, and systems. We now appreciate that no one muscle is responsible for one specific movement, and that the brain does not think in terms of muscles but rather in terms of successfully completing a movement.

Let us embrace and cherish the rich history, language, and definitions of anatomy, while appreciating the need for new explanations, new models, and a new understanding of anatomy based on sound scientific principles and continuity. John Sharkey MSc, Clinical Anatomist (British Association of Clinical Anatomists)

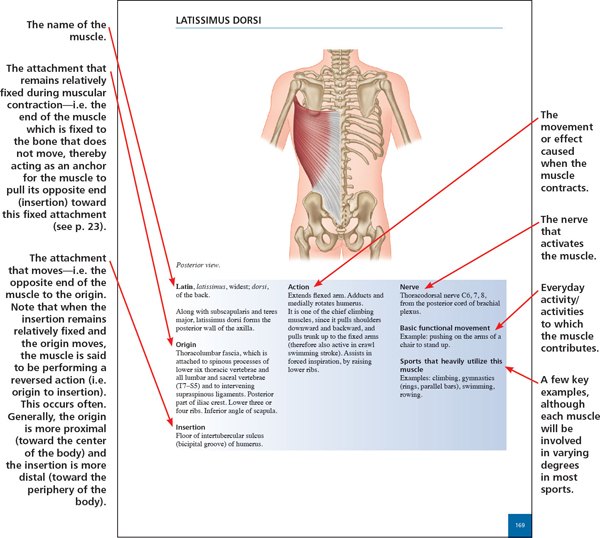

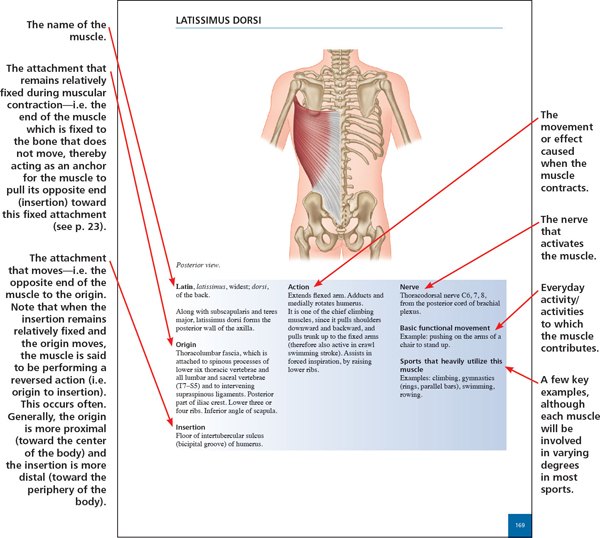

This book is designed in quick-reference format to offer useful information about the main skeletal muscles that are central to sport, dance, exercise science, and bodywork therapy. Each muscle section is color-coded for ease of reference. Enough detail is included regarding each muscles origin, insertion, action, and nerve innervation (including the nerves common course or path) to meet the requirements of the student and practitioner of bodywork, movement therapies, and movement arts. The book aims to present that information accurately and in a particularly clear and user-friendly format, especially as anatomy can seem heavily laden with technical terminology. Technical terms are therefore explained in parenthesis throughout the text.

The information about each muscle is presented in a uniform style throughout. An example is given below, with the meanings of headings explained in bold (some muscles will have abbreviated versions of this).

Layers

Throughout this text, the term

layer is used to describe the anatomy of fascial (connective) tissue or the positioning of one structure relative to another. The use of this term is for convenience, and the sense should not be taken literallythere are no physical layers in the human body. Layers are created when a dissection is performed and tissues are separated by scalpel or blunt dissection.

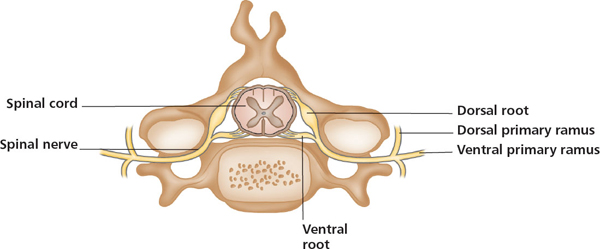

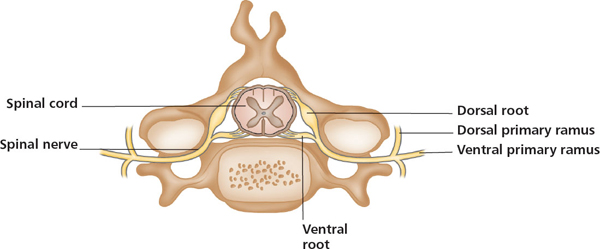

The nervous system comprises: The central nervous system (CNS)i.e. the brain and spinal cord. the brain and spinal cord.

The peripheral nervous system (PNS), including the autonomic nervous systemi.e. all neural structures outside the brain and spinal cord. The PNS consists of 12. In this book the relevant peripheral nerve supply is listed with each muscle, for those who need to know. However, information about the spinal segment from which the nerve fibers emanate often differs between the various sources. This is because it is extremely challenging for clinical anatomists to trace the route of an individual nerve fiber through the intertwining maze of other nerve fibers as it passes through its plexus (plexus = a network of nerves: from Latin plectere = to braid).

Therefore, such information has been derived mainly from empirical clinical observation, rather than through dissection of the body. In order to give the most accurate information possible, the method devised by Florence Peterson Kendall and Elizabeth Kendall McCreary has been duplicated in this book. Kendall and McCreary (1983) integrated information from six well-known anatomy reference texts: those written by Cunningham, deJong, Bumke and Foerster, Gray, Haymaker and Woodhall, and Spalteholz. Adopting the same procedure, and then cross-matching the results with those of Kendall and McCreary, the following system of emphasizing the most important nerve roots for each muscle has been used in this book.

Chichester, England

Chichester, England  North Atlantic Books Berkeley, California Copyright 2003, 2008 by Chris Jarmey, and this third edition in 2015, copyright by Chris Jarmey and John Sharkey. All rights reserved. No portion of this book, except for brief review, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the written permission of the publisher. For information, contact Lotus Publishing or North Atlantic Books. First published in 2003, the second edition published in 2008, and this third edition published in 2015 by Lotus Publishing Apple Tree Cottage, Inlands Road, Nutbourne, Chichester, PO18 8RJ and North Atlantic Books Berkeley, California Anatomical Drawings Amanda Williams Exercise Drawings Matt Lambert Cover Design Jasmine Hromjak The Concise Book of Muscles, Third Edition is sponsored and published by the Society for the Study of Native Arts and Sciences (dba North Atlantic Books), an educational nonprofit based in Berkeley, California, that collaborates with partners to develop cross-cultural perspectives, nurture holistic views of art, science, the humanities, and healing, and seed personal and global transformation by publishing work on the relationship of body, spirit, and nature. North Atlantic Books publications are available through most bookstores.

North Atlantic Books Berkeley, California Copyright 2003, 2008 by Chris Jarmey, and this third edition in 2015, copyright by Chris Jarmey and John Sharkey. All rights reserved. No portion of this book, except for brief review, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the written permission of the publisher. For information, contact Lotus Publishing or North Atlantic Books. First published in 2003, the second edition published in 2008, and this third edition published in 2015 by Lotus Publishing Apple Tree Cottage, Inlands Road, Nutbourne, Chichester, PO18 8RJ and North Atlantic Books Berkeley, California Anatomical Drawings Amanda Williams Exercise Drawings Matt Lambert Cover Design Jasmine Hromjak The Concise Book of Muscles, Third Edition is sponsored and published by the Society for the Study of Native Arts and Sciences (dba North Atlantic Books), an educational nonprofit based in Berkeley, California, that collaborates with partners to develop cross-cultural perspectives, nurture holistic views of art, science, the humanities, and healing, and seed personal and global transformation by publishing work on the relationship of body, spirit, and nature. North Atlantic Books publications are available through most bookstores.  The nervous system comprises: The central nervous system (CNS)i.e. the brain and spinal cord. the brain and spinal cord.

The nervous system comprises: The central nervous system (CNS)i.e. the brain and spinal cord. the brain and spinal cord.