Table of Contents

This book is dedicated with humble appreciation to Dr. Ken Kyungho Min, founder of the University of California at Berkeleys Martial Arts Program (UCMAP). It was Dr. Mins encouragement to explore all aspects of martial arts that made this book possible.

PART 1: OVERVIEW

INTRODUCTION

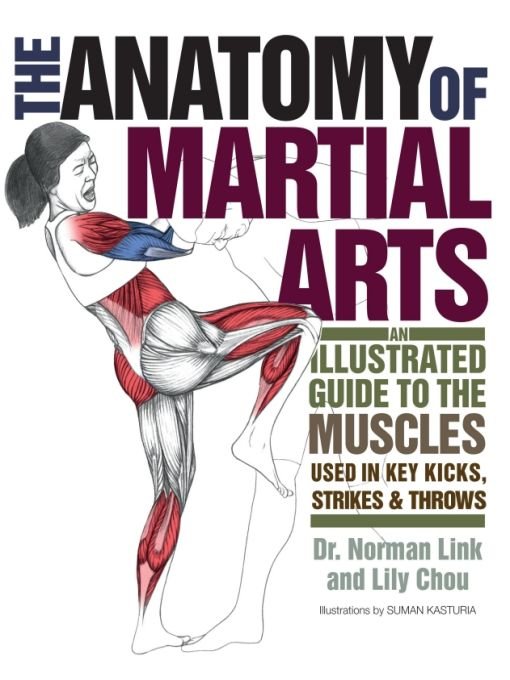

Welcome to The Anatomy of Martial Arts: An Illustrated Guide to the Muscles Used in Key Kicks, Strikes and Throws. Between the two authors, we have about 60 years of formal martial arts training and yet are just starting to scratch the surface of learning. This is not an attempt at being humble; its a simple fact. As you train in whatever martial arts you choose, your body changes. With luck, it is sculpted to flow with the techniques that the art demands, and with time there should be a steady improvement. However, when looking at martial arts training over a longer period of time, our bodies inevitably age and our physical abilities slowly decline. The bottom line is that we spend more and more of our time trying to adapt the techniques we know to an ever-changing set of bones and muscles.

For this book weve been limited to showing 50 techniques from as wide an array of martial arts as we could. Thus, we chose a number of hand strikes (including breaks), kicks, throws, weapon and grappling techniques, and rolls and falls. While a beginning martial arts student may find this book interesting, it will be most useful to intermediate and advanced practitioners of the martial arts.

Unlike most other martial arts books, this book assumes that the reader is already familiar with the techniques that are featured. We dont teach any techniques; rather, we highlight and discuss the main muscle groups required for the technique to be performed and suggest ways to both strengthen and stretch those muscles to improve the techniques quality. Because even basic moves such as a front kick can be taught a variety of ways depending on the art in which theyre used, we hope that by emphasizing the bodys fundamental structures, particularly the musculature and kinetic chains, the foundation of each technique might be reopened to discussion.

Even if you decide that the muscles highlighted are incorrect or incomplete, then at least weve accomplished our primary goal of getting you to think about each techniques foundation. We hope that by reviewing your movements as to which muscles are being used, you can augment your training to improve the power and motion that actually drive the techniques.

ANATOMY AND MARTIAL ARTS

Every move we make, be it sitting, standing, running, or kicking, involves an elaborate choreography of the 250 skeletal (or voluntary) muscles as they move our 206 bones. These bones are arranged as follows:

29 in the head and neck

2 clavicles, or collarbones (the most commonly broken bone in the body)

2 scapulae, or shoulder blades

26 in the spine, or vertebral column

24 ribs

1 sternum

2 in the pelvis

60 in the arms (3 each) and hands (27 each)

60 in the legs (4 each) and feet (26 each)

In brief, each muscle group has a specific set of functions and is often paired with an opposing muscle or muscle group. The biceps, for example, are responsible for bending the arm at the elbow, while the triceps are responsible for straightening it. Contracting the biceps causes the arm to bend; at the same time, the triceps must relax. Any disruption in this play of opposites can affect the movement (for example, tight biceps will prevent full arm extension). The last page of this book features a color-coded illustration of the muscles and their actions. Youll also find charts in the appendix that list the key muscles and their functions.

The Anatomy of Martial Arts largely ignores the 29 bones in the head, except insofar as to recognize that the head must be protected (as with a chin tuck during a back fall). The movements of the remaining 177 bones and the muscles that move them are what make the practice of martial arts so very interesting and difficult to learn. The martial arts, when properly performed, arent just a set of actions but a veritable symphony of movements. This makes identifying the muscles involved in any given technique a challenge. Even a technique as seemingly simple as a reverse punch requires the martial artist to perform a specific sequence of actions in a specific order and with specific timing.

Its beyond the scope of this book to describe all the muscles involved in each stage of a technique; rather, this book highlights the key muscles and the kinetic groups they work in. We hope that this will help you reconsider how you perceive the various techniques and how you might improve them.

LINES OF POWER FOR MOVEMENT: KINETIC CHAINS

Power is required not only for hand strikes and kicks but also for throws, jumps, falls, and twisting out of an attackers reach. A number of people have used the term kinetic chain in reference to a power stroke of the body, or when muscles work together to produce a given line of power. While several kinetic chains have been defined and used in other works, this book features six major ones. (There are, of course, many others that can be defined, but for the sake of simplicity well stick with six.) With the remarkable complexity of even simple martial arts techniques, its rare when there are not at least two of these kinetic chains working together to produce a flow of power in a desired direction.

The six kinetic chains described below are each responsible for a different key power drive of the body. Each description includes the relative effective range, speed, and strength, as well as a couple of examples of techniques that are based on that kinetic chain.

Posterior Kinetic Chain: This forward drive of the hips (sometimes referred to as a pelvic thrust) is a medium-range, slow, strong movement thats usually used to align the drive of the legs with either the weight of the torso or an upper-body drive. This kinetic chain is perhaps the hardest one to understand and is often a central component in ki exercises and other fundamental power-generation techniques. It gets its name from the fact that the muscles involved are on the posterior side of the body and range from the hamstrings in the legs all the way up to the latissimus dorsi in the upper back. It is essential in a standard reverse punch or a groundwork bridge. Leg Extension Kinetic Chain: This long-range, fairly quick, strong drive involves the extension of the leg at the hip, knee, and ankle joints. Its usually associated with a kick or a lifting action of the body.

Hip Turn Kinetic Chain: This drive is short-range, slow, and very strong. The turn of the hip is intimately connected with leg movements and body twists, such as the sweeping hip throw.

Lateral Kinetic Chain: This medium-range, slow, mid-strength drive involves twisting the body to one side, such as with a side kick, some throws, and many ground techniques.

Shoulder Turn Kinetic Chain: This drive is short-range, medium speed, and strong. The turn of the shoulder is intimately connected with arm movements and, to a lesser extent, body twists. Hand strikes are common examples.