DISCLAIMER

Throughout this book, company and product names are included with project ideas. These are for example only and do not imply endorsement.

All uncredited photos were taken by the author. All photos other than author photos or those credited to staff at the Watershed Agricultural Council are in the public domain and not subject to copyright.

While the activities described in this book are generally chosen as safe, there is inherent risk in any outdoor activity. Consult your doctor before engaging in any outdoor exercise program, and be sure you have the necessary skills before engaging in any potentially hazardous outdoor activity.

This book contains numerous links to websites that provide additional resources such as videos, applications, and fact sheets. Although these links worked at the time of writing, websites change often, and you may encounter dead links.

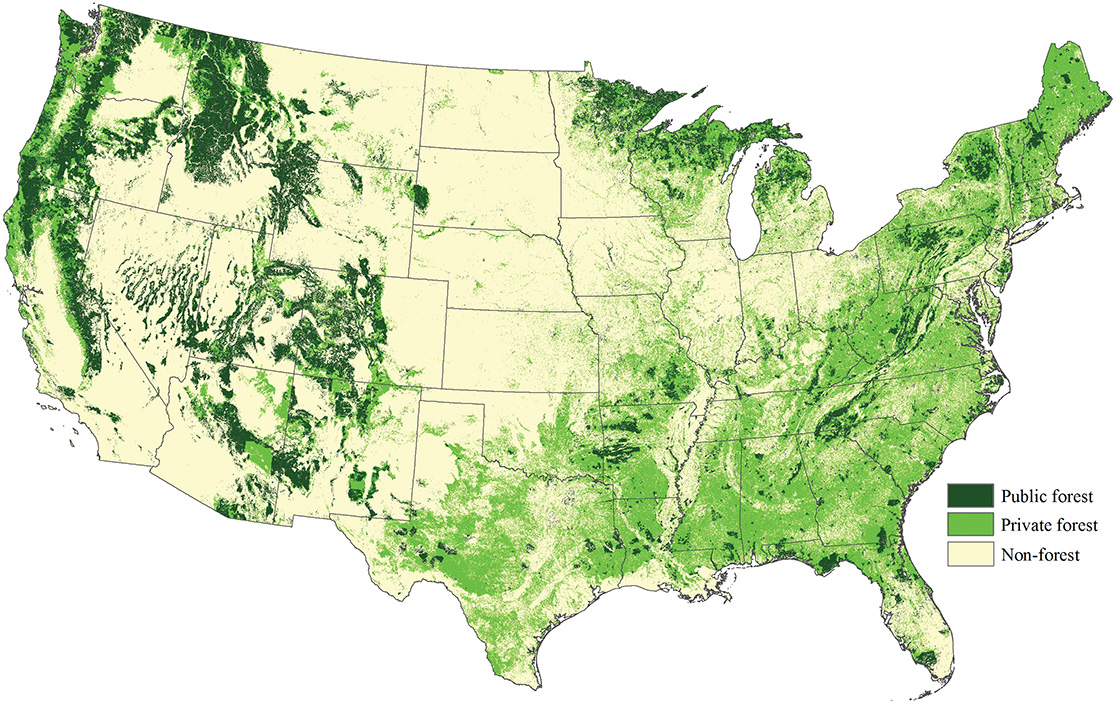

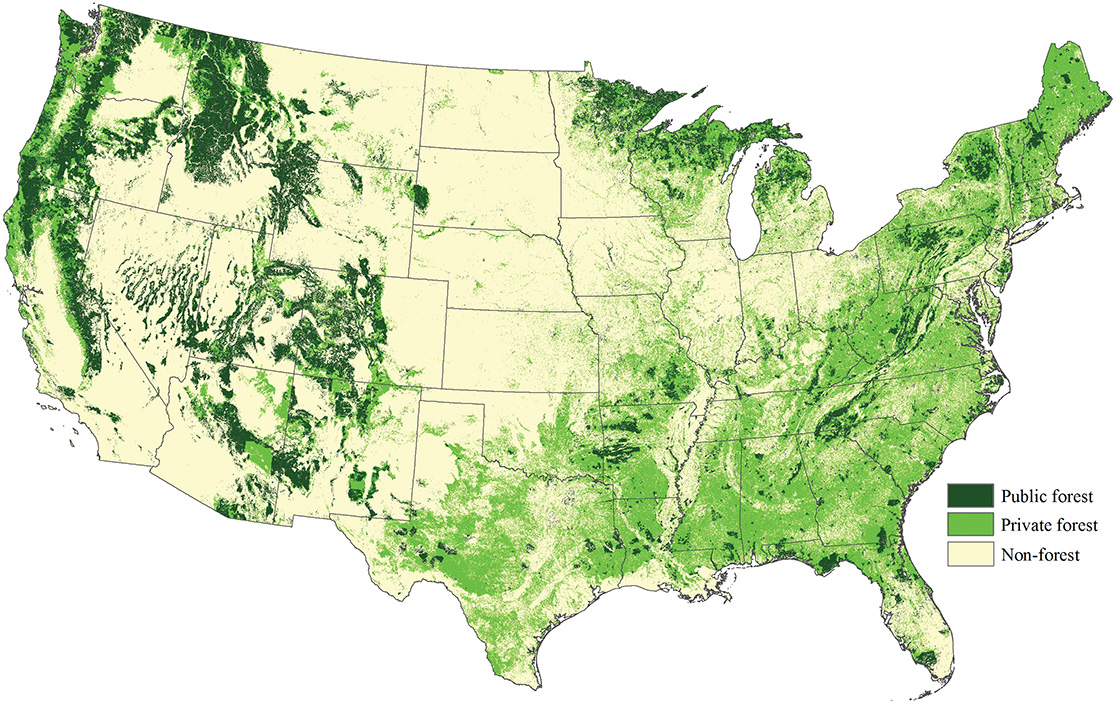

Because most US woodland is privately owned, landowners like you are essential for sustaining the many values of woods, including wildlife habitat, rural scenery, and water quality. Photo credit: public domain

Private Landowners Rule!

If you go off into a far, far forest and get very quiet, youll come to understand that youre connected with everything.

Alan Watts

Late in the summer of 2007, my coworker and fellow forester Tom Foulkrod stood before a group of high-ranking diplomats from several southeast Asian nations. They had flown halfway around the world in suits, dress shoes, and heels to learn about how we care for the forests where Tom and I work, in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York.

Im not sure what the diplomats expected when their bus arrived at the site of Toms woods walk, the Frost Valley Model Forest. Im certain they did not expect Tom. He was twenty years younger than the youngest among them. Instead of a suit, he wore Carhartts, a t-shirt, and hiking boots. To top it off, he sported a red beard that would make any Viking proud.

Tom could not have come from a more different life than those of the group he was now to lead, but he didnt let those differences bother him. He set off on the hike with his typical gusto, pointing out challenges New Yorks woodlands faced and ways we were trying to overcome them. He talked about how we protect trails from washing away during storms. He talked about invasive species, some of which the group knew from their home countries. He talked about deer pressure on the young trees and shrubs.

None of it was sticking. The groupall English-speakingfollowed along with uninterested expressions. It was a pretty boring conversation to start, Tom told me later. I was talking at them, not with them.

He still doesnt know what made him mention his 12 acres of fields, woods, and swamp in nearby Stamford. Maybe it was desperation as he grasped for anything that would help these bigwigs feel like they hadnt wasted their time coming here.

At once the groups whole manner changed. Hands flew up. Tom was surprised, but he gestured to one of the diplomats.

Whats the deer pressure on your land? the man asked.

Tom answered, and more hands rose. So you manage 12 acres?

No, I own 12, Tom corrected. We saved up and own it outright.

Another hand. What did you pay for your property?

And another: Do you have to keep paying for your property?

As fast as Tom could answer one question, two more hands went up. The formerly reserved diplomats now waved their hands like schoolchildren.

I kept figuring the next question would be the last, Tom told me, but the questions just kept coming.

When the time came for the group to leave for the next site on their tour, Tom led them back to their bus. They asked him questions the whole way there. They invited him to the next stop, a farm an hour up the road, and Tom was so happy that he accepted. The group kept right on asking him questions about his 12 acres the rest of the day.

That night Tom went out on his back deck and looked over his land. A grin blossomed on his face. Hed owned this property for two years, but hed never thought of it as anything unusual. For him it was a nice few acres to see deer, birds, and the occasional coyote. After that day, though, Tom saw his property in a new light, as something rare and special.

And it is. The fact that an everyday, middle-class guy like Tom can own woodland is unusual around the world. Our planet has about 9.6 billion acres of forested land. Of that, governments own more than 85 percent.

In countries like those from the delegation that visited Tom, the percentage is even higher. China owns all its nations forests. So do Russia and Indonesia. Brazil and Canada both own 90 percent.

America is different. Were unique among countries with large forests in that most of those woods are in private, not public hands. Private citizens own 56 percent of US forests.

Who owns these private forests? Big corporations? Wealthy land barons? The 1 percent of the 1 percent?

Nope. Families like yours, mine, and Toms hold the largest share. In total, more than 10 million family owners control 260 million acres of US forests.

Just as Tom didnt think his 12 acres were anything impressive, it might be hard to think of your wooded land as a forest or something important to the broader landscape. But make no mistake. Even if you only own a few acres of trees, you own a forest, or at least part of one. Together with your neighbors and the other millions of woodland owners like you across this nation, you and your land provide the rest of us with enormous value.

The United States is unique among countries with large amounts of forestland in that most of its forest is privately owned, especially in eastern states.

Wherever youre reading this, take a moment and look around. Youll see the contributions of private woodland owners. The wood floor, furniture, and framing of the building youre in probably all came from private woods. 92 percent of US lumber production comes from trees on private land.

How about that glass of water or cup of coffee? 88 percent of all rain and snow in the United From there it flows into streams, rivers, groundwater, and ultimately through your faucet.

Large mammals like the endangered Florida panther have wide ranges, making them especially dependent on private lands. These animals need vast areas of open space uninterrupted by development to survive, so they cross both public and private lands often throughout their lives. Photo credit: John Hollingsworth, US Fish and Wildlife Service

The birds chirping outside your window, as well as a host of other wildlife, need private land too. Colorado State University biologists estimate that private land provides habitat for 85 percent of United States wildlife.

Next page