this book is dedicated to my parents, Julio and Maria Mercado, whose love and respect for film continues to inspire me.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to all the individuals who helped in the preparation of this book through their kind support, contributions, and expertise.

I am sincerely grateful to the team at Focal Press: Robert Clements, Anne McGee, Dennis Schaefer, Chris Simpson, and especially Elinor Actipis, who provided me with invaluable guidance and suggestions from start to finish (including a great title), took the time to nurture a first time author, and had an unwavering commitment to preserving the original concept behind this book.

I also want to thank my colleagues in the Film & Media Studies Department at Hunter College of the City University of New York, whose passion and dedication to studying and teaching the art and craft of film has always been a source of encouragement and inspiration, among them: Richard Barsam, Michael Gitlin, Andrew Lund, Ivone Margulies, Joe McElhaney, Robert Stanley, Renato Tonelli, Shanti Thakur, and Joel Zuker. I also want to acknowledge the support of Hunter College President Jennifer J. Raab, Provost Vita C. Rabinowitz, Dean Shirley Clay Scott, and Film & Media Studies Department Chair James Roman, who foster an atmosphere that encourages faculty scholarship and excellence in teaching.

I am also grateful to Jerry Carlson, David Davidson, Herman Lew, and Lana Lin at the City College of the City University of New York, who were generous with their knowledge and mentorship, and to Elvis Maynard for his research assistance.

My reviewers provided me with wonderful suggestions and undoubtedly made this a better book than it would have been: David A. Anselmi at the University of California Berkeley Extension, David Crossman at Ravensbourne College of Design and Communication, David Tainer at DePaul University, and especially Katherine Hurbis-Cherrier at New York University, who always had le mot juste whenever I needed it.

Special thanks go to my sweet wife Yuki Takeshima, who was endlessly patient, supportive, and understanding through many late nights of writing, and unconditionally sacrificed a lot of her time so that I could stare at a monitor day after day.

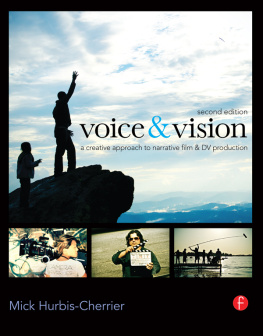

But I am most grateful of all to my teacher, colleague, mentor, and friend, Mick Hurbis-Cherrier, whose tireless and illuminating comments, assistance, ideas, and guidance were instrumental in the development of the manuscript. His teachings and passion for cinema resonate through every page of the book you now hold in your hands.

Up in the Air. Jason Reitman, 2009.

Introduction

A group of friends and I went to see Jason Reitman's Up in the Air (2009) soon after it was released. Returning from the theatre, we discussed the movie; some of my friends liked it, some found it a bit slow, and others thought it was a masterpiece. At one point, the discussion focused on the cinematography, and one of my friends recalled how brilliant the shot shown on the opposite page was. Regardless of our opinions on the film, we all agreed with him about how beautiful and meaningful that shot had been. Interestingly, we could recall everything about this shot clearly: its composition, when it had happened in the film, and most importantly why it was such a great shot. While there were many other interesting shots and moments in the film, there was something particularly special about this shot that really resonated with all of us, regardless of how we felt about the film as a whole. What was it? Was it the composition of the shot? The acting? Or was there something else that made this shot so memorable?

To understand why this shot works so well, we need to know a bit about the context in which it appears. Natalie (Anna Kendrick), is a corporate up and comer who devises a way to fire employees remotely using webcams, saving her company (a professional corporate termination service) a lot of money spent flying their specialists to companies who need their services. Ryan (George Clooney), a senior firing specialist who is dubious of a system that precludes all real human contact, questions its soundness. Their boss promptly puts Ryan in charge of Natalie's education, and the two are sent out as a team, so Natalie can experience firsthand firing someone face to face. After a heart-wrenching montage of employees reacting to the news of their firing, the film cuts to a shot of Natalie sitting alone in a room full of empty office chairs as she waits for Ryan. When he arrives to pick her up he asks her if she is OK, but she shrugs off the question, and they leave together. Now that we know the backstory of the shot, we can better understand what makes it work so well. In terms of its composition, the shot does not appear to be particularly complex. It looks like a simple wide shot of Natalie surrounded by empty office chairs. If we look closer, however, and break down the shot into its visual elements, the rules of composition used to arrange them in the frame, and its technical aspects, a more complex picture emerges, literally.