EARTH AND WORLD

KELLY OLIVER

EARTH AND WORLD

Philosophy After the Apollo Missions

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2015 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53906-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Oliver, Kelly, 1958

Earth and world : philosophy after the Apollo missions / Kelly Oliver

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-17086-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-17087-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53906-7 (e-book)

1. Philosophy21st century. 2. Earth (Planet)Miscellanea. 3. Philosophy, Modern. I. Title.

B805 O46 2015

190dc23

2014035071

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER DESIGN: Martin Hinze

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Chuck and Teri

thanks for our many adventures, enjoying the wonders of earth

From the viewpoint of the processes in the universe and in nature, and their statistically overwhelming probabilities, the coming into being of the earth out of cosmic processes, the formation of organic life out of inorganic processes, the evolution of man, finally, out of processes of organic life are all infinite improbabilities, they are miracles.

Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future

CONTENTS

T hanks to Jennifer Fay for ongoing discussions of Earth and World and for her work on the inhospitable world in film. Thanks to Cynthia Willett for reading the entire manuscript and giving me helpful feedback and for her inspiring work on Interspecies Ethics. Thanks to the graduate students in my seminar on Earth and World at Vanderbilt. And thanks to my research assistants over the years that I have been working on this project, Juliana Lewis, Melinda Hall, and Geoffrey Adelsberg. As always, I appreciate the support and companionship of my beloved Beni, Juracn, and Yukiy, who take the edge off the solitary pursuit of writing.

Mens conception of themselves and of each other has always depended on their notion of the earth.

ARCHIBALD MACLEISH, RIDERS ON EARTH TOGETHER, BROTHERS IN ETERNAL COLD

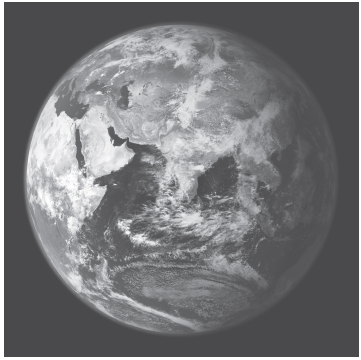

FIGURE 1.1. Blue Marble. Image by Reto Stckli, rendered by Robert Simmon. Based on data from the MODIS Science Team

T he spectacular images from the 1968 and 1972 Apollo missions to the moon, Earthrise and Blue Marble, are the most disseminated photographs in history.

Whereas Earthrise shows the earth rising over the moon, with elliptical fragments of each (the moon is in the foreground, a stark contrast from the blue and white earth in the background), the later image, Blue Marble, is the first photograph of the whole earth, round with intense blues and swirling white clouds so textured and rich that it conjures the three-dimensional sphere.

FIGURE 1.2. Earthrise. Image Credit: NASA

In the frozen depths of the cold war, and over a decade after the Soviets launched the first satellite to orbit Earth, Sputnik, these images were framed by rhetoric about the unity of mankind floating together on a lonely planet. At the same time as vowing to win the space race with the Soviet Union, the United States wrapped the Apollo missions in transnational discourse of representing all of mankind. Indeed, these now iconic images ignited an array of seemingly contradictory reactions. Seeing Earth from space generated new discussions of the fragile planet, lonely and unique, in need of protection. These tendencies gave birth to the environmental movement. At the same time, the Apollo missions spawned movements to unite the planet through technology. Heralded as mans greatest triumph, the moon missions lead to a flurry of speculation on not just the technological mastery of the world, or of the planet, but also of the universe. While seeing Earth from space caused some to wax poetic about Earth as our only home, it led others to imagine life off-world on other planets. While aimed at the moon, these missions brought the Earth into focus as never before.

The photographs of Earth from space sparked movements aimed at conquering our home planet just as we had now conquered space. Indeed, critics of these early ventures into space asked why we were concentrating so many resources on the moon when we had plenty of problems here on Earth, not the least of which was the threat of nuclear war (Time 1969). The Apollo missions were a direct outgrowth of this threat in terms not only of the significance of the race to space but also rocket technologies, which originated with military developments in World War II. The atom bombs dropped in Japan in 1945 heralded the nuclear age with the threat of total annihilation. And the development of rockets by both the United States and Germany as part of military strategies in WWII gave rise to rockets launched into space by the USSR and USA in decades that followed. Indeed, the U.S. recruited German scientists to work with NASA.

Within a decade, we had gone from world war and the threat of genocide of an entire people, to the possibility of nuclear war and the threat of annihilation of the entire human race. And, within another decade or two (with Sputnik and then the Lunar Orbiter and Apollo missions and photographs of Earth from space), the world gave way to the planetary and the global. Following Heidegger, we might call this the globalization of the world picture. The Earth had become a picture even before the photo was taken. Within a few short decades, the rocket science used by the military in WWII had given rise to the globalism that we have inherited today. From global telecommunications such as cell phones and Internet to global environmental movements, the Apollo missions moved us from thinking about a world at war to thinking about the unification of the entire globe. If, after seeing Earthrise, as Archibald MacLeish claims, Mens conception of themselves and of each other has always depended on their notion of the earth, then, in order to understand ourselves and our interactions with other earthlings we need to ponder the meaning of earth and globe and the place of human and nonhuman worlds in relation to them.

FROM GLOBALIZATION TO EARTH ETHICS

In this book, we explore some philosophical reflections on