Praxedis G. Guerrero

I. Literary and Combat Articles

II. Thoughts

III. Revolutionary Chronicles

IV. Magns Reminisces

Praxedis G. Guerrero Has Died 142

Praxedis G. Guerrero 145

Introduction

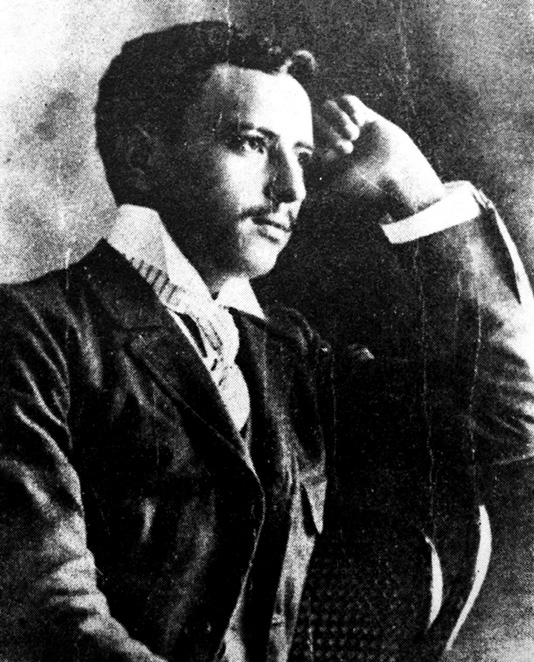

The militant Mexican anarchist and revolutionary martyr Praxedis G. Guerrero arguably merits his comrade Ricardo Flores Magns laudatory characterization of him as a sublime figure in the revolutionary history of the world. During his short but highly illuminating life, Guerrero participated as a central figure in the transnational revolutionary network established by the Organizational Council of the Mexican Liberal Party (PLM), which was dedicated firstly to deposing the tyrant Porfirio Daz and thereafter to promoting anarchist revolution throughout Mexico according to the slogan Tierra y Libertad (Land and Freedom).

As Magn writes in his reminisces about Guerrero following his death early in the Revolution, there was little immediate indication from the childhood of Praxedis, whose father was a local indigenous chief and whose mother was the daughter of a Spanish count, that he would be anything other than bourgeois. His familys hacienda in Los Altos de Ibarra, Guanajuato, comprised thousands of acres that were worked by hundreds of farmhands. Yet Praxedis was privileged to have developed an exceptional sensitivity and an exceptional brain that led him to adopt the revolutionary proletarian cause upon his maturation. After resigning his military post, he returned to Guanajuato to attend to his ill father and manage the familys hacienda, and it was from his fathers bookshelf that Praxedis first encountered the writings of Victor Hugo, Maxim Gorky, Lev Tolstoy, Mikhail Bakunin, and Peter Kropotkin.

In 1904, consummating the dream Tolstoy had envisioned but could never effect, Guerrero definitively abandoned his aristocratic upbringing. With his comrades Francisco Manrique and Manuel Vzquez, he left Mexico for the U.S., where he sold his labor as a miner in Colorado, a lumberjack in Texas, a longshoreman in San Francisco, and a copper and coal miner in Arizona. He founded the newspaper Alba Roja (Red Dawn) with Francisco and Manuel while in San Francisco, and it was likely in this way that he brought himself to the attention to the newly established Organizational Council of the Mexican Liberal Party, founded in St. Louis in 1905 by the exiled radicals Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magn, Juan and Manuel Sarabia, Librado Rivera, Antonio I. Villarreal, and Rosalo Bustamante. In Douglas, Arizona, Praxedis met and befriended Manuel Sarabia and requested successfully to affiliate himself with the PLM. Days after the suppression of the June 1906 Cananea strike in the desert of Sonora, which had been launched by thousands of Mexican miners demanding an eight-hour work day and higher wages, Praxedis founded the organization Free Workers with his comrades toward the end of propagating the Liberal ideal among the miners of the region. He also established a local PLM group in Morenci counting some fifty members, as a counterpart to the Liberal Club of Douglas. The failure of the Councils plans for an insurrection against the dictatorship in the border towns of Ciudad Jurez, Nogales, and Jimneza plot that was organized to coincide with Independence Day, 16 September 1906and the subsequent arrest of Ricardo, Antonio, and Librado in Los Angeles for having violated existing neutrality laws between the U.S. and Mexico launched Guerrero into the position of principal responsibility for the cause. Indeed, as Albro argues, Praxedis effectively led the PLMs struggle during the three highly significant years of 1907 to 1910, corresponding to the time that the Councils better-known organizers were imprisoned, and ending with his death in the Revolution.

Praxedis was named a Special Delegate of the PLMs Organizational Council in June 1907, and the next month he distributed a public call for justice in the case of Manuel Sarabia, his comrade and roommate in Douglas, Arizona, who had been kidnapped, deported, and imprisoned in Hermosillo, Sonora, at the hands of Dazs henchmen. This crime sparked an international outcry that resulted in Sarabias release following a show trial that acquitted the militants captors. Then, following the arrest of another exiled Liberal, Lzaro Gutirrez de Lara, Guerrero moved to Los Angeles to collaborate with Sarabia and Enrique Flores Magn in editing and publishing the newspaper Revolucin, which began its run in June 1907 . Sarabia was soon arrested on the very same charges as Magn, Villarreal, and Rivera, but was subsequently rescued by Elizabeth Trowbridge, a socialist activist and heiress from Boston, who paid his bail, married him, and escaped with to England. Although Praxedis cut off communication with Manuel over this decision to elope, Sarabia nonetheless would circulate Guerreros writings throughout much of the European continent.

Seeking to relaunch the Revolution against Daz, Praxedis left Los Angeles with Francisco Manrique for El Paso, where they organized a widespread insurrection in Mexico, set for 2425 June 1908. Guerrero commanded some sixty armed Liberal groups divided across five geographical zones comprising Mexico that were prepared to revolt. Nonetheless, as in the case of the uprising organized two years prior, this new revolutionary plan was largely foiled by the two States transnational spy network: hundreds of conspirators were arrested and sent to the San Juan de Ula prison in Veracruz, where many perished. Still, Liberal forces managed to engage in three battles against federal troops during this time: in Las Vacas, Coahuila, a village which the Liberals likely would have taken, had they not run out of ammunition during the firefight; Viesca, Coahuila, where the insurgents liberated the local jail, expropriated State funds, and proclaimed the PLMs program, but were driven out by Dazs forces; and Palomas, Chihuahua, an attack that Praxedis personally led, but which led to the death of his comrade Francisco. Guerrero commemorates these three revolutionary episodes in heroic chronicles translated in this volume. The pathos permeating the Palomas chronicle celebrates Franciscos martyrdom, serving both to foreshadow Guerreros own end and to laud the revolutionary commitment of his childhood friend, who, like Praxedis, had been born into wealth but who had repudiated such privilege to dedicate himself wholeheartedly to the struggle.