Contents

Guide

An enthusiastic chronicle of the years between 1840 and 1919 This is a boisterous, unglamorous period largely lost to collective memory, and Sante takes much pleasure in identifying its remains. His joy in his subject is obvious, as is the thoroughness of his research. Sante [is] a bookworm and an outsider, and proud of it.

Sally S. Eckhoff, Village Voice Literary Supplement

A systematic, well-researched historical account of drinking, drugging, whoring, murder, corruption, vice and miscellaneous mayhem in late-19th- and early-20th-century New York City Well-crafted and tightly written.

Michael Winerip, The Boston Globe

Fascinating We should all be grateful to Luc Sante [for producing] this entertaining and sobering history of New Yorks dark side [It] delights the reader with constant felicities Replete not only with wit but with feeling.

Jim Holt, The Philadelphia Inquirer

A tour-de-force [Sante] has a novelists eye for detail and an aesthetes taste for anecdote Low Life is unquestionably a book that can be read for instruction about New York as well as for pleasure.

David Rieff, Times Literary Supplement

Makes the stories of Edgar Allan Poe seem less the products of dark imaginings than efficient reportage [Sante] strews his pages with fabulous bits of offbeat erudition. Colorful, elegant, and witty [,] Low Life, with its perfectly chosen anecdotes and austere, epigrammatic prose, is a superb work of social history. It deserves something stronger than conventional praise and a longer life than any of its protagonists enjoyed.

Patricia Storace, Cond Nast Traveler

L OW L IFE

Lures and Snares of Old New York

[ FARRAR STRAUS GIROUX ]

NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead.

William Blake

Proverbs of Hell

Three people who contributed in fundamental ways to the birth of this book are no longer alive to receive my thanks; it is with sadness and gratitude that I salute the memory of Jonathan Lieberson, Luis Sanjurjo, and Chris Cox. This project would never have gotten under way without the early enthusiasm and skills of John Herman and Mark Polizotti; my debt to them is enormous. My research was made possible with the patient and knowledgeable assistance of the staffs of the Mercantile Library and the Local History room at the New York Public Library, as well as of Meredith Collins at Brown Brothers, Gretchen Viehmann and Terry Ariano at the Museum of the City of New York, Patricia Paladines at the New-York Historical Society, Terry Geesken and Mary Corliss at the Museum of Modern Art Film Stills Archive, Eleanor J. Mish at the American Museum of the Moving Image, and the staff of the research library at the Municipal Archives. For allowing me to spin off some of my preoccupations into article form during the gestation period of this work I am obliged to Duncan Stalker (in his capacities at Manhattan, Inc., The Cond Nast Traveler, and the ill-fated New York Sunday Post) and to Wendy Lesser at The Threepenny Review. For miscellaneous advice, suggestions, comfort, sympathy, and encouragement I give thanks to Elizabeth and Richard Devereaux, David Higginbotham and Elizabeth Sacre, Jim Jarmusch and Sara Driver, Paul Pavel, Simon Pettet, Darryl Pinckney, Irv Schenkler, David Shapiro, and Chuck Wachtel. For being an exemplary and kind landlady during a difficult time I hail Martha Fedorko. For their extraordinary industry, perseverance, fortitude, and, above all, belief, I am grateful to my agent, Joy Harris, and my editors, Jonathan Galassi and Rick Moody. I owe an inexpressible debt to April Bernard, who felt every bump along the road and suffered them and me with humor, gallantry, sagacity, and charity. And I wish to thank my parents, Lucien and Denise Sante. This first book is for them.

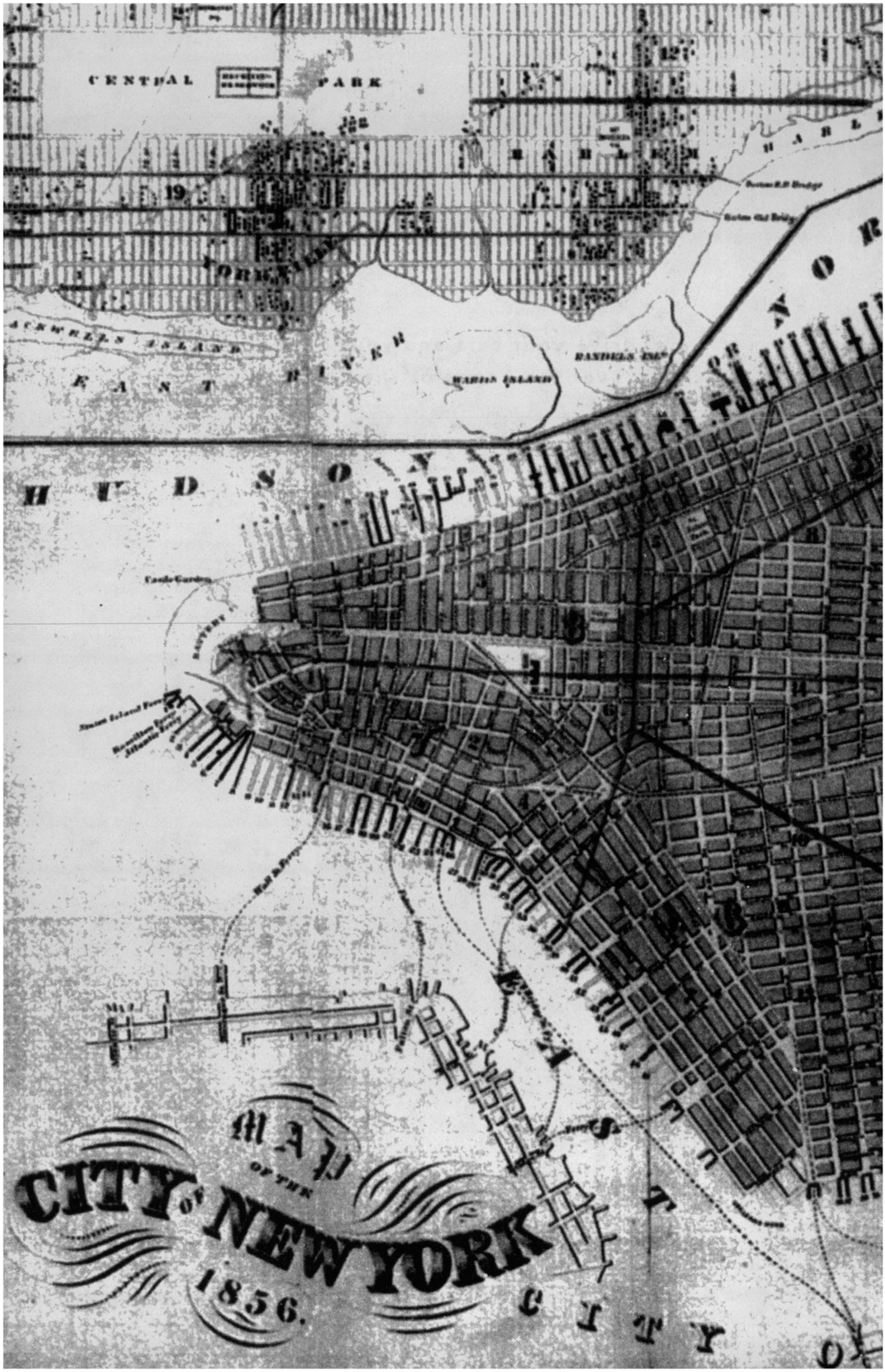

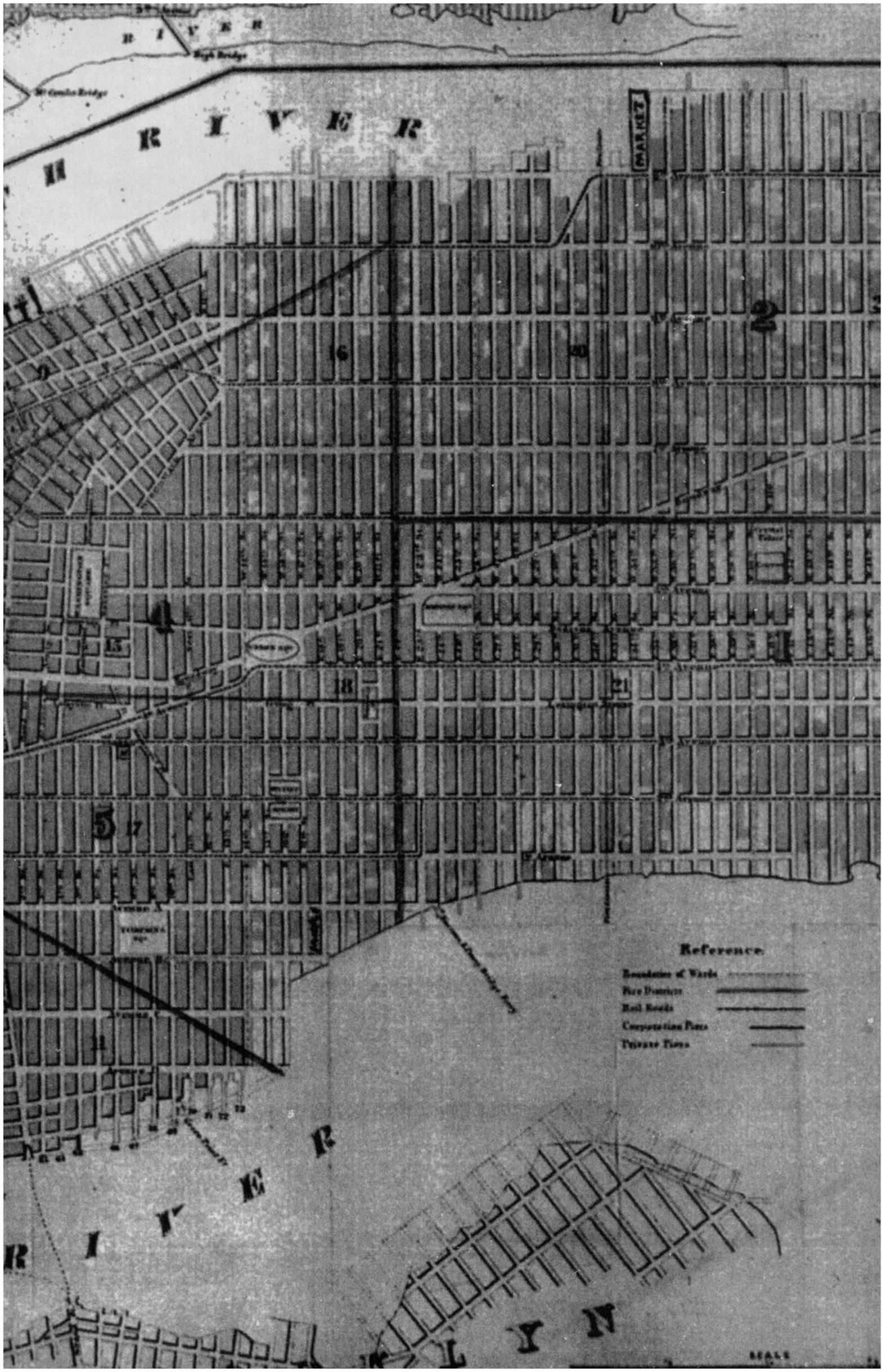

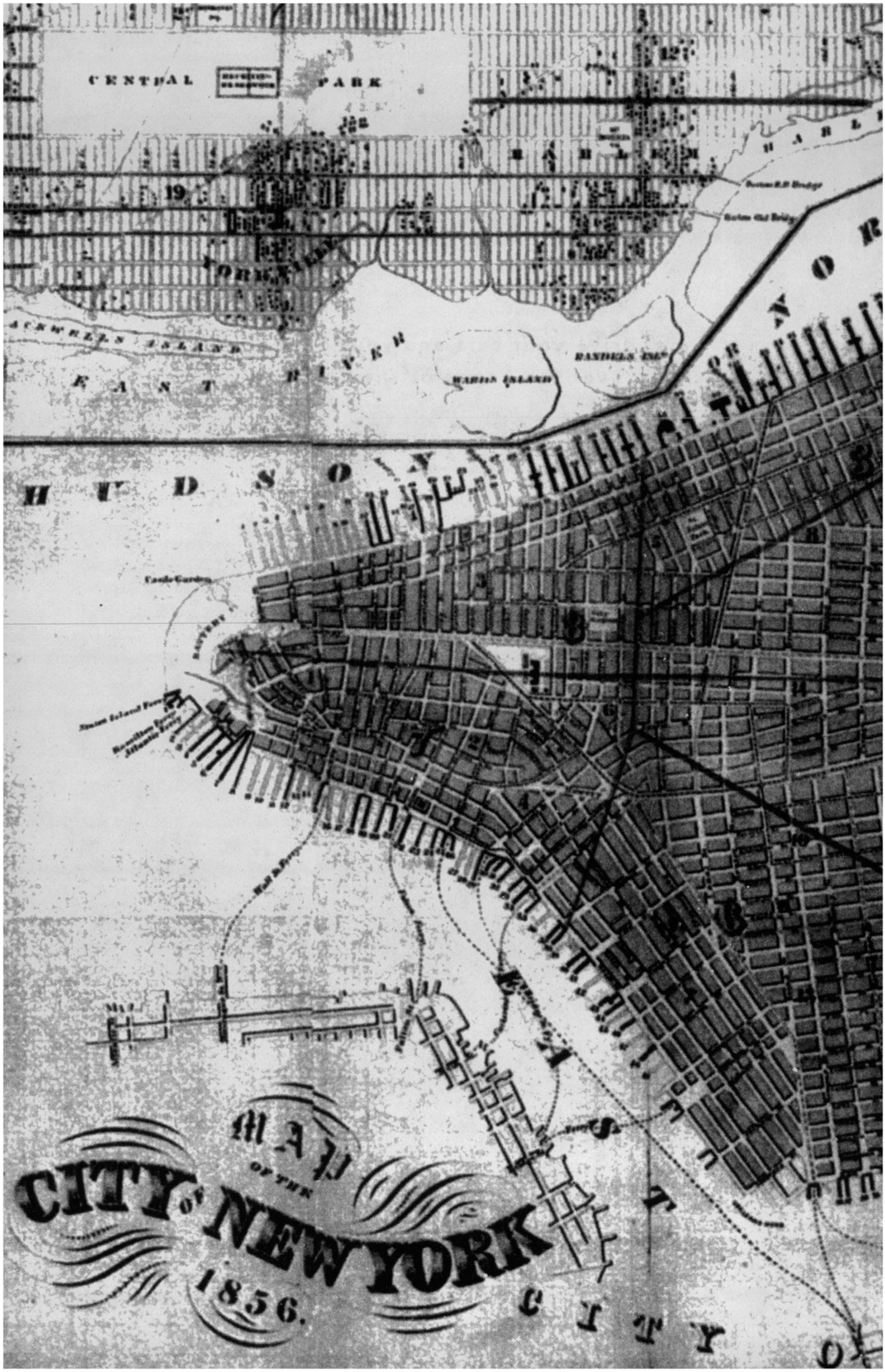

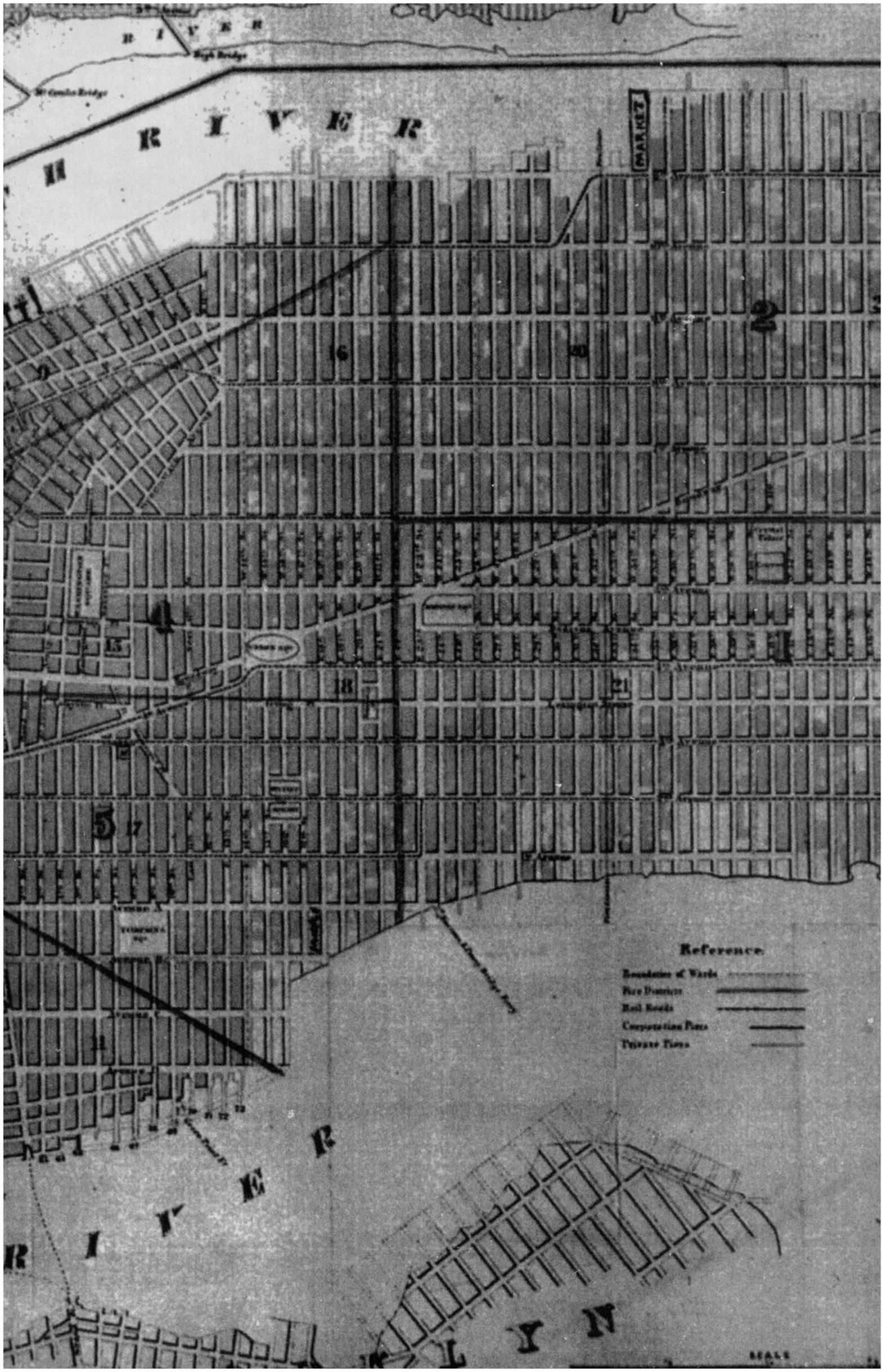

THIS IS A BOOK ABOUT NEW YORK. IT MAY BE BRIEFLY DESCRIBED AS CONCERNING THE VICES AND LURES THAT THE CITY PROFFERED TO THE LOWER CLASSES IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, AND THE STREETS AND ALLEYS that were their theater. Its time span covers the roughly eighty years of the citys adolescence and early adulthood: from about 1840, when New York began to be transformed by railroads, tenements, and other accoutrements of the modern city, until 1919, which was not only the year of the Volstead Act and the Red Scare but a portal into a new technological era that would alter the city yet again. Geographically, the story is confined to Manhattan, and mostly dwells on the realms of attraction and concealment, the bazaars and the underworld: the Bowery, Satans Circus, Hells Hundred Acres, Hells Kitchen, the slums, the waterfront. In spite of its being thus limited in temporal and topographical scope, this is also, I believe, a book about New York City today.

The firmament that is New York is greater than the sum of its constituent parts. It is a city and it is also a creature, a mentality, a disease, a threat, an electromagnet, a cheap stage set, an accident corridor. It is an implausible character, a monstrous vortex of contradictions, an attraction-repulsion mechanism so extreme no one could have made it up. New York, which has been called the capital of the twentieth century, as Paris was that of the nineteenth, would seem on the face of it to be founded on progress, on change, on the bulldozing of what has faded to make way for the next thing, the thing after that, the future. The lure of the new is built right into its name; it is the part of the name that actually registers, since the York, a commemoration of a colonial lineage, carries no resonance and exists only as a vestige. New York is incarnated by Manhattan (the other boroughs, noble, useful, and significant though they may be, are merely adjuncts), and Manhattan is a finite space that cannot be expanded but only continually resurfaced and reconfigured. Manhattan is a wonderland of real estate speculation, a hot center whose temperature cannot but increase as population increases and desirability remains several paces ahead of capacity. The myth of Manhattan, therefore, is cast in the future tense. It does not hark back to a heroic past, lacks its Romulus and Remus (except in the image of that transaction between Peter Minuit and the Canarsies, which is simply the first clever deal, the primordial ground-floor entry). New York has no truck with the past. It expels its dead.

The dead, however, are a notoriously perverse and unmanageable lot. They tend not to remain safely buried, and in fact resist all efforts at obliterating their traces. Cultures that glorify and memorialize their dead have simply found a clever way to satisfy and therefore quiet them. When the dead are endlessly represented in monuments, images, memorials, and ceremonies, their vigor passes into these objects and events; it is safely defused, made anodyne. New York, which is founded on forward motion and is thus loath to acknowledge its dead, merely causes them to walk, endlessly unsatisfied and unburied, to invade the precincts of supposed progress, to lay chill hands on the heedless present, which does not know how to identify the forces that tug at its rationality.