TERRA

NOVA

To my son, Everett

This was the object of the Declaration of Independence. Not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take.

Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Henry Lee (May 8, 1825)

Contents

List of Illustrations

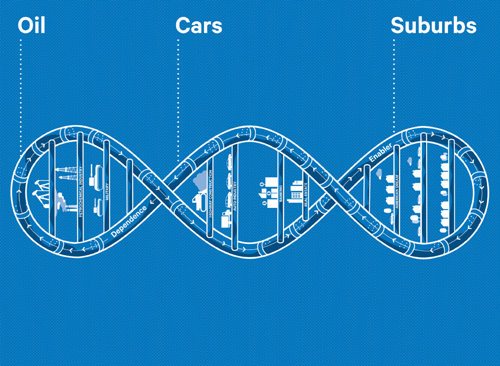

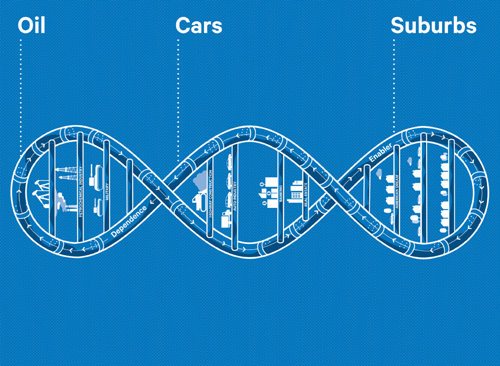

Figure No. 1 The connections among oil, cars, and suburbs fueled the twentieth-century American economy but now reinforce a lifestyle dependent on long commutes, gas-fed automobiles, and the energy in oil.

How the Sirens Sing

All these things have thus come to an end.

Homer, The Odyssey

First of all, youll run into the Sirens.

They seduce all men who come across them.

Whoever unwittingly goes past them

and hears the Sirens call never gets back.

His wife and infant children in his home

will never stand beside him full of joy.

No. Instead, the Sirens clear-toned song

will captivate his heart.

Homer, The Odyssey, Book 12

On his long journey home after the Trojan War, the hero Odysseus came to an island where the goddess Circe advised him to avoid the Sirens, beautiful winged monsters whose irresistible song lured mariners to their death. Forewarned but undaunted, Odysseus sailed into peril anyway. His plan: He would listen but not give in. The wily hero packed his mens ears with beeswax and commanded them to tie him to the ships mast. There he stood as they sailed into treacherous waters; the Sirens called to him, and he heard their song. As Circe had predicted, he longed to go to them, to cast away everything he held dear. He shouted at his men, ordered, then begged them to set him free, but the mast was strong, the rope held fast, and his men couldnt hear his pleas. And so Odysseus did not perish, but emerged on the other side of the Siren song wiser, saner, and prepared to complete his journey home.

Like Odysseuss less fortunate peers, Americans have been hearkening to a Siren call. Monsters have been singing to us for decades, and we have found their music persuasive, beautiful, and often irresistible, even though we know that it beckons us to our own destruction. Despite our best intentions, oil, cars, and suburbs have become the modern American Sirens.

You know the dangers well; they are in the news practically every night, and have been a generation or more. Oil brings us hatred from the people who have the wells; wars in the Middle East to protect the supply; economic shocks and cycles of unemployment, inflation, and foreclosure; poisoned air and waters; and a climate altered by carbon released from its millennial slumber underground. Cars isolate us in metal boxes, discourage us from exercise, expose us to accidents and sudden death, and squander our time on congested freeways, while each year requiring more roads to fragment the landscape, entomb farm fields, cleave neighborhoods, and drain our collective coffers in servitude to lifeless prairies of asphalt. Suburbs, originally conceived as garden cities, are criticized for their monotony, segregation, sprawl, outrageous property taxes, obsequious service to retailers, and aesthetic, social, and cultural barrenness, but in my book the problem with suburbs as currently constituted is that they require automobiles, and automobiles require oil: Suburbs force us to drive.

Oil, cars, and suburbs sing to us constantly and harmoniously. Their song bridges history and landscape to appeal to our identity as a free nation; we hear it on the television and we say to ourselves: We wouldnt be Americans without these things. So the trap is laid. A seduction composed of our own desires, the song is composed of the choices and actions of our parents and grandparents and sustained by our own choices and actions. These thingsoil, cars, suburbsare not monsters on their own, but only monsters as we have made them, and because of what they make us do.

They were never meant to be such a difficulty; they were intended to provide joy, freedom, and wealth. For most of the twentieth century, connecting these three buoyed the American Dream of a better material life for every generation. So successful was the combination that many Americans began to think oil-cars-suburbs was the American Dream, confusing means with ends. Yet it seems that these same means have now run their course: For the first time since the founding of the nation, the quality of life in America is in decline; the price, perhaps, of too much of a good thing.

Signs of an eras end are all around us, yet blithely we continue as Americans have done since the time of William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt. The advantages of oil as an energy source are obvious and attractiveespecially when its cheap and abundant. Autos have been a mark of personal liberty for at least a century. A variety of interests represent the detached, single-family home on a cul-de-sac as the epitome of lifes ambitions. Oil, cars, and suburbs sing to us all the time.

Not Listening

I have to say I have been caught humming the song, too. Im a kid from the suburbs, like a hundred million others; gas stations, mini-malls, and sprawling ranch homes defined the landscape of my youth in northern California. Some of my earliest memories are of squabbling with my brother in the back of the family Ford on the way to the store or the swim club or the innumerable other errands for which driving was the only practical alternative. My family had a modest suburban house near a creek, constructed where an orchard had been. It was two miles from our house to the closest store, a long walk with groceries but just a quick jaunt in the carwhether it was Dads Rambler, Moms Ford, Dads Mercury, Moms Volvo, Dads Acura, Moms Subaru, or Dads Lexus. I marked my youth by the cars my parents drove.

When I was in high school, my grandparents in rural Colorado offered to help me buy a car. Every young man needed a car, they said. That was especially true where they lived, where it was twenty miles in twenty minutes to the closest town. But I was more interested in my Uncle Larrys dusty and forlorn fifty-fourvolume set of the Great Books of the Western World in the den. My grandparents thought I was crazy to spend Friday nights reading John Locke and Adam Smith; my brother and sister suspected it was a ploy to avoid carting them around town.

Later when I went to college at the University of California, Davis, I bought my own car, a beat-up, used blue 1977 Volvo station wagon. My friends and I affectionately named her Brnnhilde, leader of the Valkyrie. She took me home on weekends and let me escape to the Sierra Nevada mountains in a few hours; but around town, I discovered I rather liked to ride my bike. Davis was one of the few places in the country where the weather, terrain, and traffic engineering had conspired to make a bicyclists paradise. Weeks would pass when the only transportation I needed, I provided by my own pedal power. It was a local freedom, but a sweet one nonetheless.

Next page