REVOLUTIONS

Michael Lwy

editor

REVOLUTIONS

translated by

Todd Chretien

Original edition: Rvolutions (Paris, Hazan, 2000)

Original updated edition: Revolues (So Paulo, Boitempo, 2009)

(c) Michael Lwy, 2000, 2009

Published with the permission of Boitempo, Brazil

2020 Michael Lwy

Published in 2020 by

Haymarket Books

P.O. Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-64259-212-2

Distributed to the trade in the US through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution (www.cbsd.com) and internationally through Ingram Publisher Services International (www.ingramcontent.com).

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and Wallace Action Fund.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases by organizations and institutions. Please call 773-583-7884 or email for more information.

Cover photograph, Woman with Flag, 1928, by Tina Modotti.

Cover design by Eric Kerl.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

Contents

Michael Lwy

Gilbert Achcar

Gilbert Achcar

Rebecca Houzel & Enzo Traverso

Michael Lwy

Enzo Traverso

Bernard Oudin

Pierre Rousset

Gilbert Achcar

Janette Habel

Michael Lwy

Michael Lwy

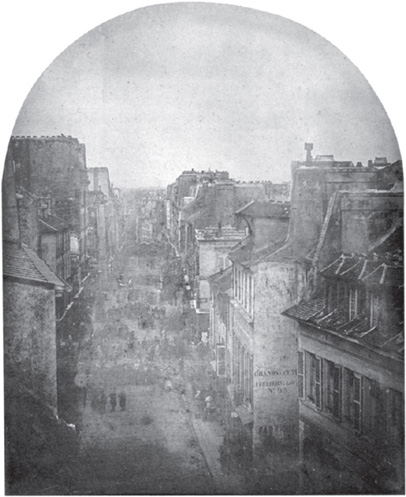

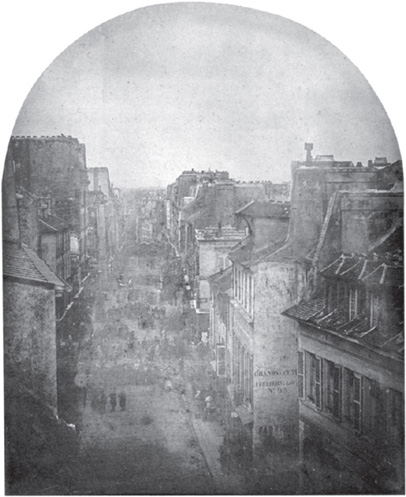

Remnants of barricades on rue Royale, 1848.

The Revolution Photographed

Michael Lwy

T wo barricades block a narrow street. The combatants are invisible, awaiting an imminent attack. The barrier that is closer up in this photograph, built out of paving stones and carriage wheels, appears dissected by a spear that might be a flagpole (could it be red?). The street is empty. We can almost hear an expectant silence.

This barricade cannot help but bring to mind rue Saint-Maur in June 1848 described by Victor Hugo in Les Misrables:

The wall was built of cobblestones. It was plumb-straight, precise, perpendicular, leveled square, reinforced with twine, lined with lead wire.... The street was deserted as far as the eye could see. All windows and doors were closed.... No one to be seen, nothing to be heard. Not a cry, not a sound, not a breath. A tomb.

Barricades before the attack, rue Saint-Maur, June 25, 1848.

A photograph of the same barricade the following day shows the scene after a battle. The street teems with people, soldiers, shock troops, bystanders. They pass between the barricades, now riddled with holes, but largely intact. The insurgents are absent. Are they dead, taken prisoner, or have they fled? What is certain is that they have lost.

These two daguerreotypes, taken from a window on June 25 and 26, 1848, by a certain Thibautabout whom we know very littleare among the first pieces of photographic evidence of a revolution.

Barricades after the attack, rue Saint-Maur, June 26, 1848.

We have a third entry dated from this same epoch taken by Hippolyte Bayard of a demolished barricade on la rue Royale. It is a melancholic image. All that remains of the insurgents utopian dream are piles of scattered stones. The street seems deserted, but the presence of some carts and wheelbarrows suggests that someone is preparing to repave it. The battle is over. Order reigns in Paris.

There is a sharp contrast between these first images of revolutionary barricadesmagnificent, yet immobile, enigmatic, and distantand those in Barcelona almost a century later. Sandbags are substituted for cobblestones. This time, the photographer isnt on a balcony, but closer up, or even among the insurgents. And, most importantly, we see the faces of the combatants, their smiles, their untrained hands holding rifles, and their raised fists. Yet, despite these changes, the barricade is always present, synonymous with popular uprisings, with revolutionary initiative. It is no accident that the hymn of the CNT (National Confederation of Workers), the great anarchist union, begins with the call: To the barricades! To the barricades!

Another change of scene: we are in May of 2008. The paving stones are once again dug up from the street, and these rebels, who are almost all young people, are building a barricade in cheerful solidarity. But this time, unlike in Barcelona in 1936 or in nineteenth-century Paris, there are no rifles. They will not kill the enemy; instead they taunt and mock him, and once in a while a protester grazes a police officer with a stone. There is a lot of noise and smoke, but their defense of the barricade does not lead to the rebels executions, or to them being gunned down by the forces of order. Rather, the fight ends with the youths dispersal and their regrouping in another part of the city.

Lets return for a moment to the barricades of June 1848, the beginning of the photographic history of revolutions. These constitute a historic guide, what Marx called the start of the civil war in its most terrible aspect, the war of labor against capital. And they introduce a significant new meaning to the word revolution: it no longer implies simply a change in the form of the state, but an attempt to subvert the whole bourgeois order.

What was the politico-military efficacy of a barricade? For Auguste Blanquiof all nineteenth-century revolutionaries he undoubtedly considered this question most closelybarricades were indispensable for an uprisings triumph, as long as the lessons from the defeat of June 1848 were taken into account. As he explained in great detail in Instructions for an

These technical and tactical considerations did not prevent barricades from rising up at the heart of subsequent revolutionary crises. In Western Europeand sometimes in Latin America and Russia, but not in Asiathey became almost synonymous with the notion of revolution itself. From the beginning of the nineteenth century until 1968 and beyond, barricades persisted as the material symbol of the act of insurrection. As the embodiment of subversion, the barricade appears in the city center armed with flags and rifles in an asymmetrical confrontation with the canons and machine guns of the forces of order.

A magical moment, unforgettable light, interrupting the course of ordinary events, the revolution can better be grasped by an image than a concept. It survives and spreads through images and particularly, since the end of the nineteenth century, through photographic images.

Of course, photography cant be a substitute for historiography, but photos can capture what no text can communicate: certain faces, certain gestures, situations, movements. A photograph allows us to see, concretely, what constitutes the unifying spirit and singularity of a particular revolution. Some critics disparage the cognitive value of photographs of historical

This point of view, I believe, is debatable. It is true that photographs cannot substitute for narrative history, but this does not prevent them from being irreplaceable instruments for conveying historical knowledge. They make visible particular aspects of reality that frequently escape historians. A photo of Krupps factory may add nothing, but one showing Krupp himself posing with Hitler alongside other industrialists and bankers is a fascinating demonstration of the complicity between German capitalists and Nazism.

Next page