A WORD ON SEMANTICS

A general shortcoming of the social sciences (as opposed to the physical and biological sciences) is a lack of widely agreed-upon nomenclature. The meaning of one term to an individual archaeologist or social theorist may not be shared by others. To forestall any misconceptions, I open with a brief list and definition of problematic terms in the field of Central Asian archaeology.

CENTRAL ASIA Politically defined geographic region encompassing the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

CENTRAL EURASIA An inconsistently used geographic term encompassing Central Asia as well as adjacent regions to the north and the east, notably western Mongolia, the Tuva region of Russia, and Xinjiang, Qinghai, and Tibet in China.

EXCHANGE The transfer of goods, ideas, genes, or cultural traits between different people, whether traded, sold, coerced, bartered, stolen, or gifted.

INNER ASIA A geographic term often employed by historians and occasionally by other scholars. The term loosely parallels Central Eurasia .

NEW WORLD The Americas or the Western Hemisphere of the globethe parts of the world generally unknown to people in Europe or Asia before the expeditions of Christopher Columbus.

OLD WORLD A term usually referring to Europe, Asia, and Northern Africa.

SILK ROAD In the traditional sense, an ancient network of exchange routes connecting China to the Mediterranean; historians often claim that these originated with the Han Dynasty of China in the second century BC. In this volume, I use the term more broadly to encompass exchange through Central Asia from the third millennium BC until the modern era.

SPICE ROUTES An arbitrary term designating exchange routes parallel to but south of the Silk Road, by which a wide variety of plants were brought from across South Asia to Europe. Although exchange peaked later along the Spice Routes than along the Silk Road routes, it was essentially the same social process.

A NOTE ON DATES

While terms such as Bronze Age and Iron Age are often used to denote phases in European or West Asian history, they are not used consistently in different regions or even among scholars. Hence, I generally do not use them in this book; instead, I specify millennia or exact dates.

I have also opted not to use terms denoting Central Asian archaeological culture groups, such as Srubnaya and Andronovo, in the text; however, I use terms denoting historically documented dynasties and periods in classical antiquity.

PERSIAN EMPIRES

Median (728549 BC)

Achaemenid (550330 BC)

Parthian (247 BCAD 224)

Sasanian (AD 224651)

Samanid (AD 819999)

CALIPHATES

Rashidun (AD 63261)

Umayyad (AD 661750)

Abbasid (AD 7501258)

Ottoman (AD 15171924)

CHINESE DYNASTIES

Xia (ca. 20001600 BC)

Shang (ca. 16001046 BC)

Zhou (1046256 BC)

Warring States period (475221 BC)

Qin (221206 BC)

Han (206 BCAD 220)

Three Kingdoms period (AD 22080)

Jin (AD 265420)

Southern and Northern Dynasties (AD 420589)

Sui (AD 581618)

Tang (AD 618907)

Five Dynasties period (AD 90760)

Song (AD 9601279)

Yuan (AD 12711368)

PERIODS IN CLASSICAL ANTIQUITY

Classical Greece (410323 BC)

Hellenistic period (323146 BC)

Roman Republic (50927 BC)

Roman Empire (27 BCAD 476)

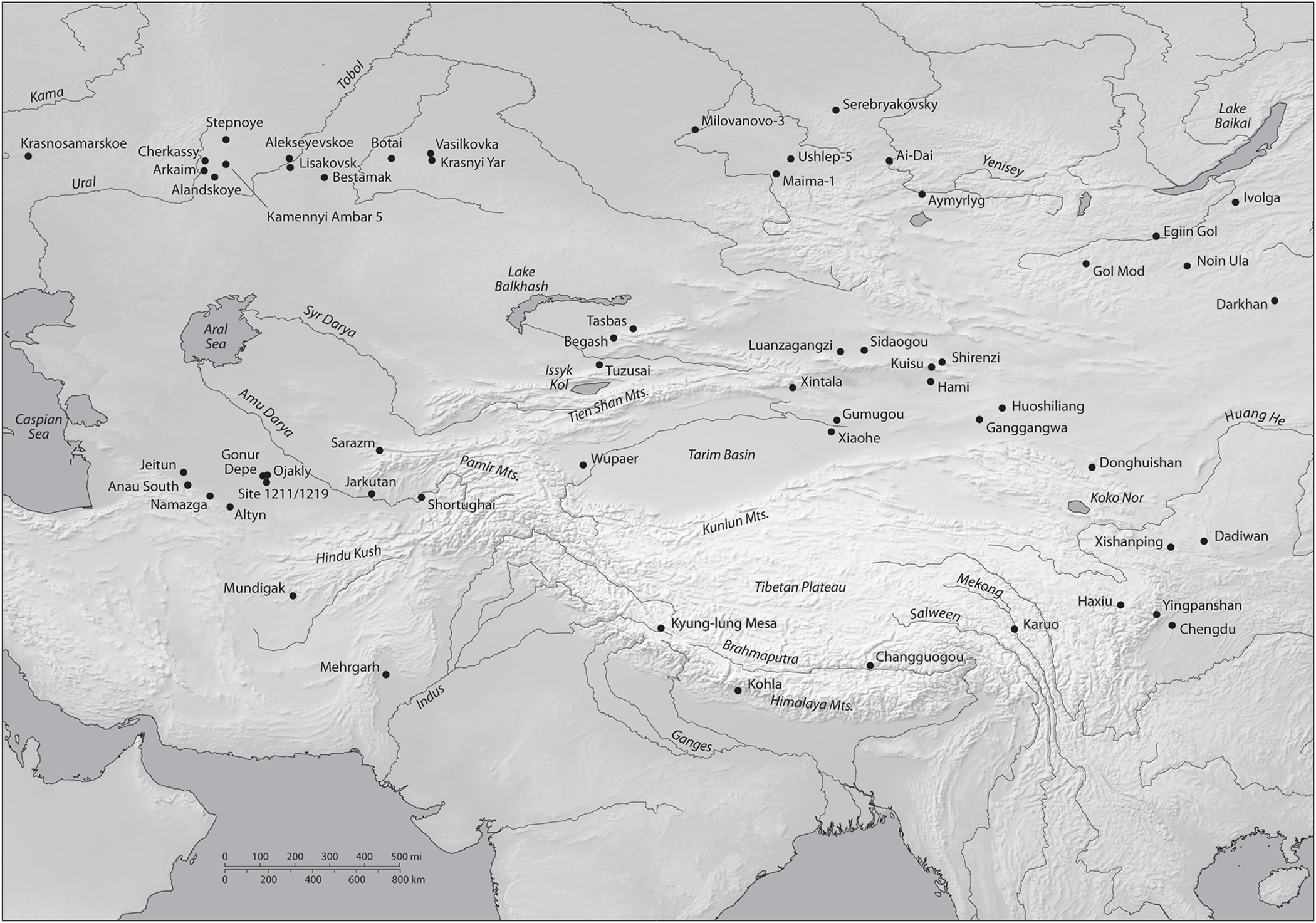

Map 1. Map of Central Eurasia, showing key archaeological sites and geographic features. These sites have provided the archaeobotanical evidence I have used to trace the spread of agricultural crops across Inner Asia.

PART I

How the Silk Road Influenced the Food You Eat

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

We have all heard the rhetoric about sustainable food systems and the slogans Feed the World and Nine billion by 2050. Likewise, we have heard about the loss of cultures around the world through the domination of one globalized culture that shapes every aspect of our daily lives, including how and what we eat. As the human population approaches nine billion, we are seeing unprecedented rates of deforestation in South America for the sole purpose of planting fields of soybean ( Glycine max ), an East Asian domesticate. Genetic diversity is being lost among crops around the globe as cloned and genetically identical hybrids are planted in fields from Russia to Mexico, and fruits and vegetables that were unheard-of in the northern temperate zone a generation ago are available all year round in markets and grocery stores. But how did humanity get to this point? How have we reached this fever pitch of global communication, commerce, and resource distribution? How did humans gain the ability to reshape the ecosystems around them and even the climate of the earth itself? The answers to these questions lie buried in the archaeological record.