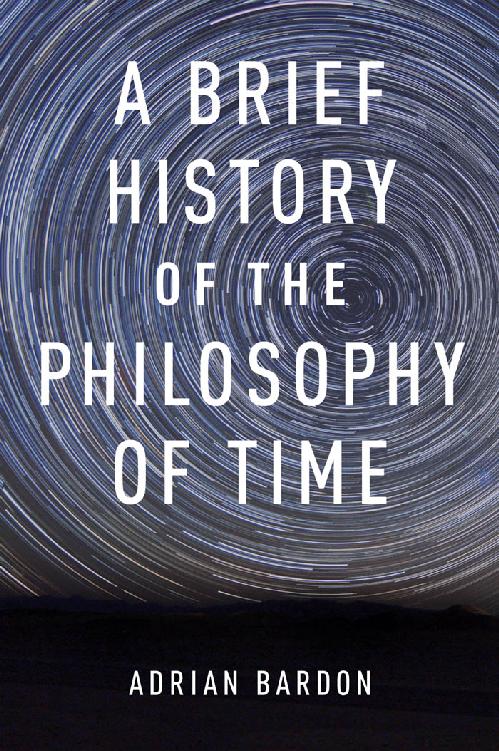

A BR IEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPH Y OF TI ME 00_Bardon_fm.indd i 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM This page intentionally left blank A BR IEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPH Y OF TI ME Adrian Bardon 00_Bardon_fm.indd iii 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitt ed by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

A BR IEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPH Y OF TI ME 00_Bardon_fm.indd i 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM This page intentionally left blank A BR IEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPH Y OF TI ME Adrian Bardon 00_Bardon_fm.indd iii 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitt ed by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bardon, Adrian. A brief history of the philosophy of time/Adrian Bardon. pages cm ISBN 9780199976454 (alk. paper)ISBN 9780199301089 (pbk. paper) ISBN 9780199977734 (updf)ISBN 9780199977741 (epub) Time. I. Title. Title.

BD638.B335 2013 115dc23 2012045782 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 00_Bardon_fm.indd iv 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM For Janna, Zev, and Max 00_Bardon_fm.indd v 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS vii 00_Bardon_fm.indd vii 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM This page intentionally left blank I am very grateful for the extensive comments given on draft s of this work by Heather Dyke, Craig Callender, L. Nathan Oaklander, Barry Dainton, Yuri Balashov, and Eric Schliesser; I am also grateful for the comments by six anonymous reviewers selected by Oxford University Press, and Greg Cook generously clarifi ed a number of issues. I used this book as a text in several recent editions of my Philosophy of Space and Time course; I am grateful for the responses I received from my students. Marcia Underwood kindly rendered the illustrations in digi tal form; her creativity and design talents improved them in many ways. My wife, Janna Levin, read the manuscript more than once, looking for errors and providing helpful comments. ix 00_Bardon_fm.indd ix 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM This page intentionally left blank A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPHY OF TIME 00_Bardon_fm.indd xi 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM This page intentionally left blank What makes time so elusive? Time couldnt be a more familiar and fundamental part of our existenceand yet, as soon as we really start thinking about it, we fi nd that there is no subject more mysteri ous and ineff able.

Ineff able is a particularly good way to put it: It means beyond words. It is diffi cult to get started in thinking about time, because it is diffi cult even to put our thoughts about time into words. Th e basic problem has been under intense consideration throughout recorded history. Th ere are two essential facts about time that most will agree on. First, we think of events as arrayed in a sort of order, where what is happening depends on where we are in that order. (Roughly speak ing, we use calendars to track this fi rst aspect of time and clocks for the second.) But these two characteristics seem to be in tension: If events are arrayed in an order, then how can we also say that they come to be and pass away? Is the passage of time real, or is it merely a subjective aspect of our experience? What is it for an event to be in 01_Bardon_intro.indd 1 4/15/2013 2:11:54 PM A B R I E F H I S TO RY O F T H E P H I L O S O P H Y O F T I M E time in the fi rst place? Upon refl ection, it is very diffi cult to explain just what a temporal description of the world really amounts to. (Roughly speak ing, we use calendars to track this fi rst aspect of time and clocks for the second.) But these two characteristics seem to be in tension: If events are arrayed in an order, then how can we also say that they come to be and pass away? Is the passage of time real, or is it merely a subjective aspect of our experience? What is it for an event to be in 01_Bardon_intro.indd 1 4/15/2013 2:11:54 PM A B R I E F H I S TO RY O F T H E P H I L O S O P H Y O F T I M E time in the fi rst place? Upon refl ection, it is very diffi cult to explain just what a temporal description of the world really amounts to.

Th is fundamental conundrum gives rise to a number of signifi cant subsidiary questions. What is the nature of our experience of time? What gives time its direction? Is travel in time possible? Is the future unwritt en, and do our choices matt er? Did time begin, and, if so, how? Th is book concerns the philosophy of time. One might well wonder how a philosophical approach to time is diff erent from a sci entifi c, psychological, sociological, literary, or other approach to the subject. Answering this question requires that we briefl y examine what philosophy is. To be honest, philosophers generally dread being asked to explain what philosophy is. Part of the problem is that philosophy is more of an activitythe activity of philosophical thinking than a subject matt er, so it is easier to demonstrate than to defi ne.

Unlike physics, mathematics, literary studies, religious studies, or just about any other fi eld of investigation, philosophy does not have its own, unique subject matt er: A given philosophical investigation might, for example, concern itself with the subject matt er of sci ence, or math, or art, or religion. Philosophy is really distinguished by the kinds of questions it asks. Philosophers ask foundational questionsquestions about, say, science: What is a scientifi c explanation? What is causation? What is the proper domain for empirical study? Philosophers ask questions about art: What is beauty? What counts as a work of art? Th ere is an unwarranted prejudice that philosophers like to dither around and ponder unanswerable questions. Nothing could be further from the truth, at least as far as contemporary academic philosophy is concerned. Th inking about philosophical questions is not viewed by philosophers as some sort of meditation, with no 01_Bardon_intro.indd 2 4/15/2013 2:11:54 PM I N T R O D U C T I O N real endpoint. Philosophers deal in tough, abstract questions, but they shun unanswerable ones like the plague.

Indeed, distinguish ing between questions that are hard to answer and questions that are meaningless or otherwise poorly formed is a big part of the philosophical enterprise. Th e inherent diffi culty of philosophical questions can make progress very slow, and this may be confused with a lack of progress. To get a bett er grasp of what time is all about, philosophers have two main jobs to do: fi gure out exactly what questions to ask, and then fi gure out how to answer them. Th e fi rst of these jobs is oft en the tougher one, and is commonly the main task in serious philosophical work. In understanding the question What is time? we start by try ing to zero in on our target. Figuring out what you are asking when asking about time is less than straightforward.

Next page

A BR IEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPH Y OF TI ME 00_Bardon_fm.indd i 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM This page intentionally left blank A BR IEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPH Y OF TI ME Adrian Bardon 00_Bardon_fm.indd iii 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitt ed by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

A BR IEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPH Y OF TI ME 00_Bardon_fm.indd i 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM This page intentionally left blank A BR IEF HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPH Y OF TI ME Adrian Bardon 00_Bardon_fm.indd iii 4/15/2013 2:10:25 PM Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitt ed by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.