Contents

Guide

Page List

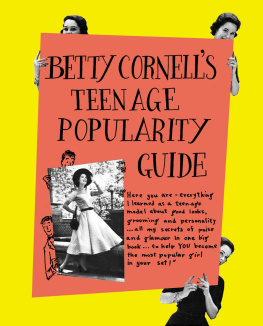

ENCHANTMENTS

Joseph Cornell

and

American Modernism

Marci Kwon

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

For David, my imagination

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

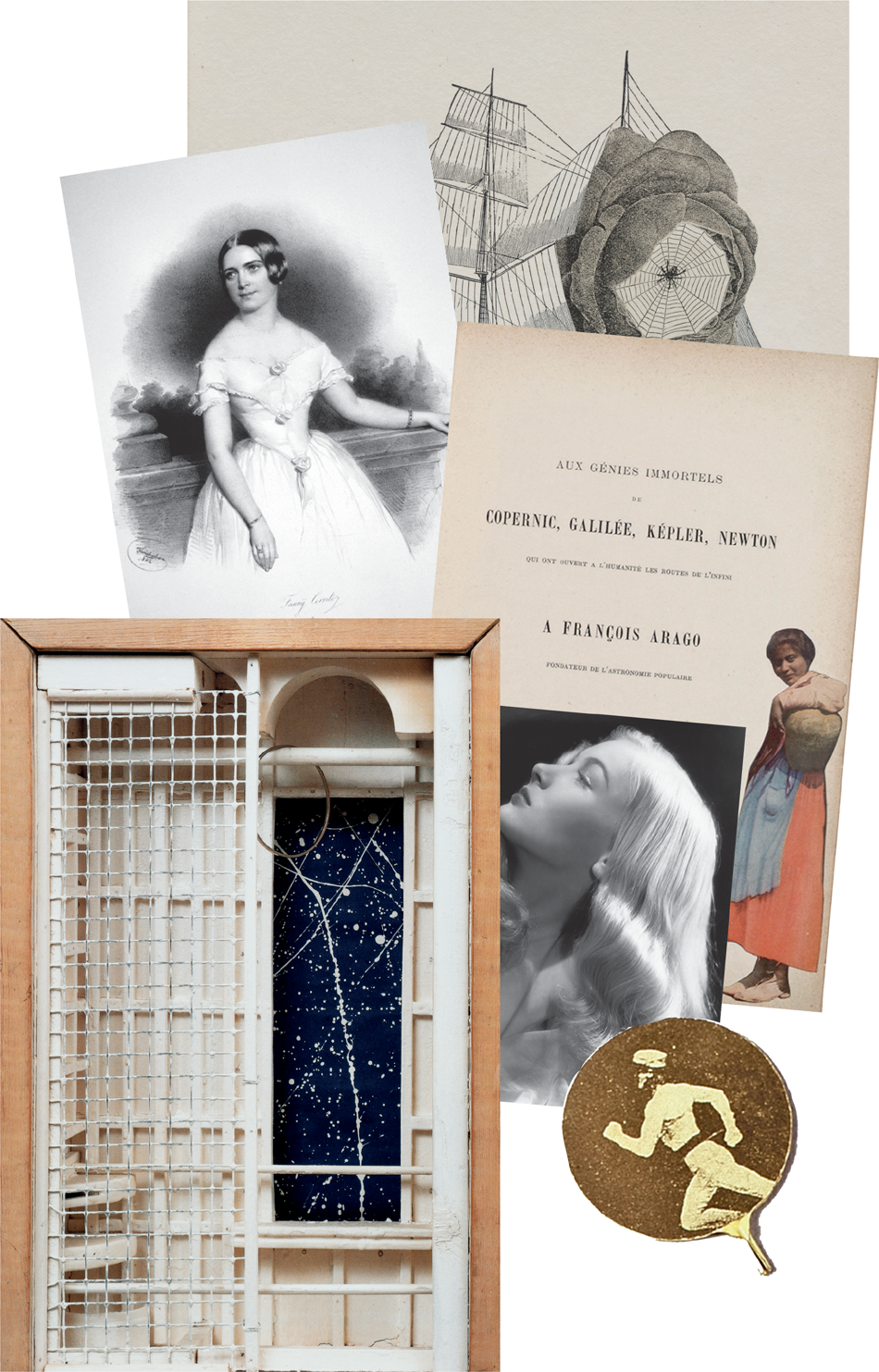

COVER : Joseph Cornell, A Swan Lake for Tamara Toumanova: Homage to the Romantic Ballet, 1946. Glass, paint, wood, photostats, mirrors, paperboard, feathers, velvet, and rhinestones, 9 13 4 inches. Menil Collection, Houston, TX, gift of Alexander Iolas.

DETAILS : endpapers,

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kwon, Marci, author.

Title: Enchantments : Joseph Cornell and American modernism / Marci Kwon.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020022667 (print) | LCCN 2020022668 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691181400 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780691215020 (ebook) Version 1.0

Subjects: LCSH: Cornell, JosephCriticism and interpretation. | Modernism (Art)United States.

Classification: LCC N6537.C66 K89 2021 (print) | LCC N6537.C66 (ebook) | DDC 709.2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020022667

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020022668

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Design by Jenny Chan / Jack Design

CONTENTS

IX

XV

PREFACE The Great and the Small

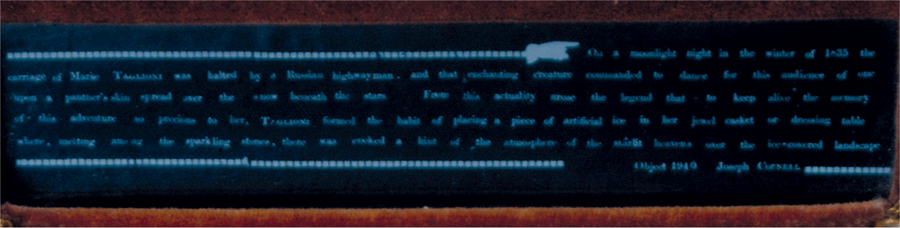

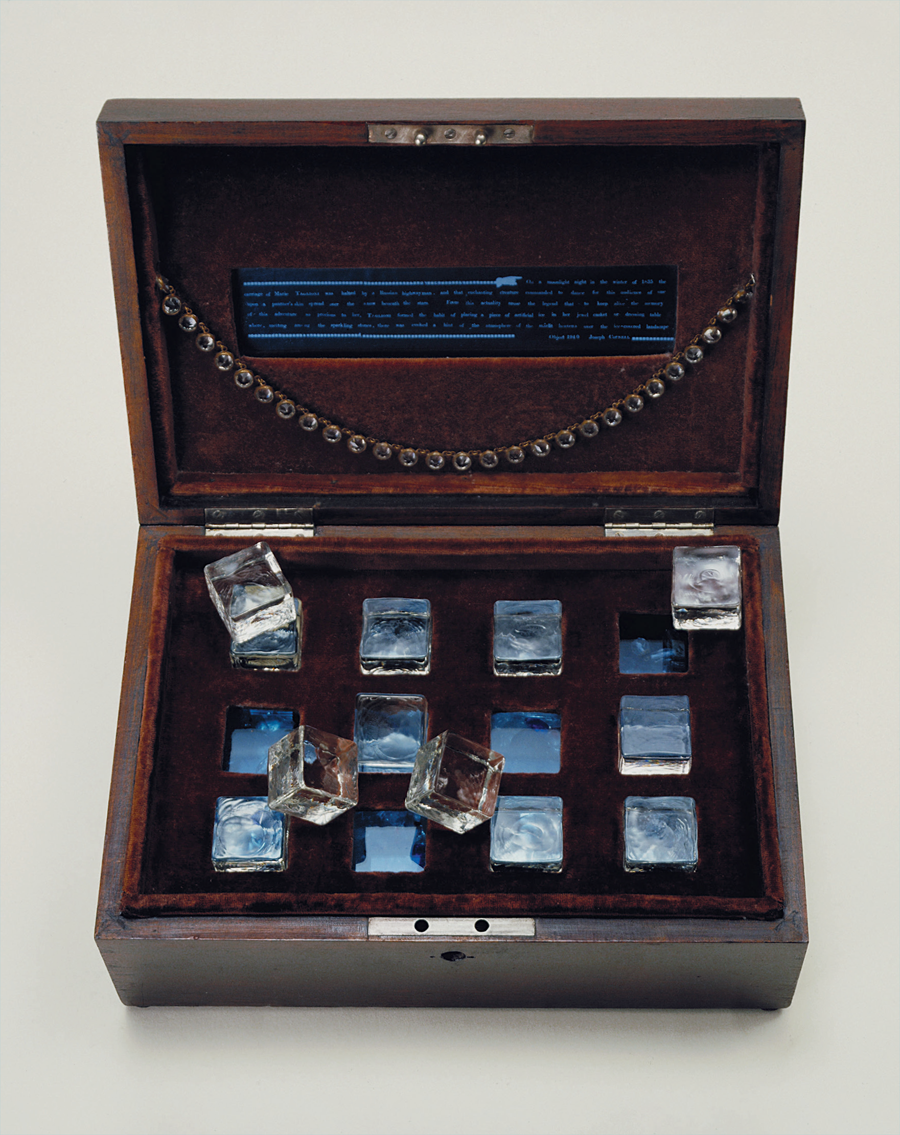

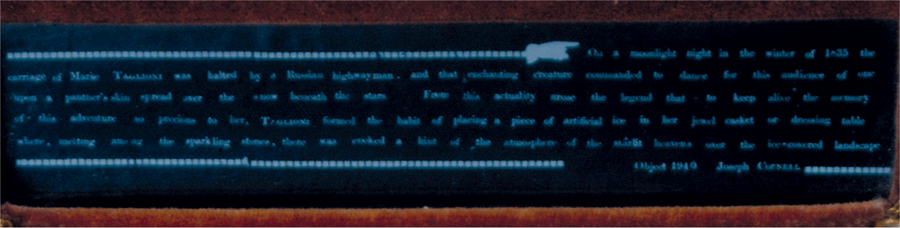

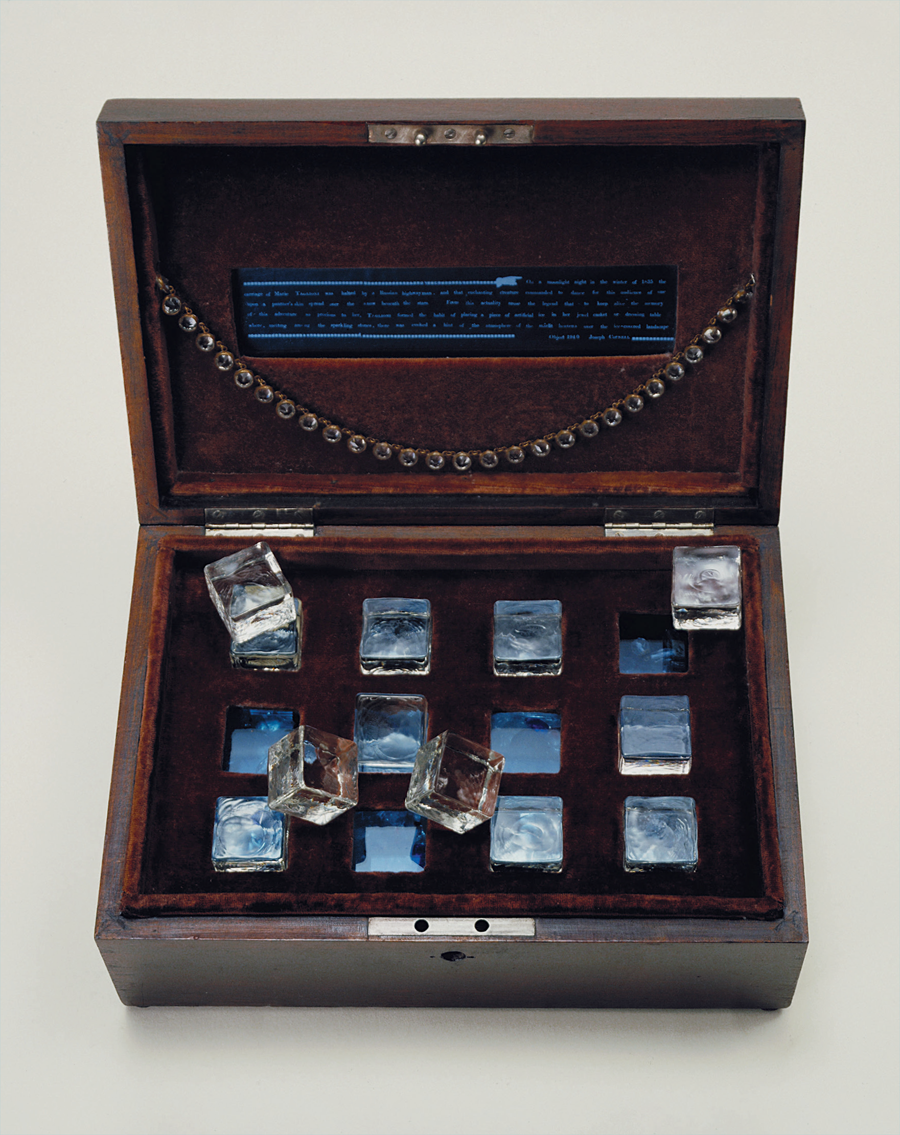

FIG. P.1 Joseph Cornell, Taglionis Jewel Casket, 1940. Velvet-lined wooden box containing glass necklace, jewelry fragments, glass chips, and glass cubes resting in slots on glass, 4 11 8 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

How very beautiful these gems are! said Dorothea, under a new current of feeling, as sudden as the gleam. It is strange how deeply colours seem to penetrate one, like scent. I suppose this is the reason why gems are used as spiritual emblems in the Revelation of St John. They look like fragments of heaven. George Eliot, Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life

I remember the first time I encountered Joseph Cornell. It was 2004, a few months into my sophomore year of college, and the Museum of Modern Art had just reopened in a gleaming building on Fifty-Third Street. Ascending the ziggurat of escalators to the fifth floor, I wandered past paintings by Czanne, Picasso, and Matisse before arriving at the gallery dedicated to Surrealism. Cornells Taglionis Jewel Casket from 1940 was installed in the corner of a large plexiglass vitrine (). While traveling on a Russian highway one snowy night in 1835, Taglionis carriage was stopped by a bandit. Unfurling a panthers skin on the icy ground, she proceeded to dance so beautifully that the robber allowed her to leave unmolested, her jewels still in her possession. The story concludes: From this actuality arose the legend that to keep alive the memory of this adventure so precious to her, TAGLIONI formed the habit of placing a piece of artificial ice in her jewel casket or dressing table where, melting among the sparkling stones, there was evoked a hint of the atmosphere of the starlit heavens over the ice-covered landscape.

At this moment, Cornells work seemed to capture everything I loved about art: its ability to call forth places and times other than my own, its unabashed investment in the magic of the aesthetic encounter. Unlike the painters and sculptors who preceded him in MoMAs galleries, Cornell eschewed the hallowed mediums of paint, marble, and bronze in favor of altogether more modest materials. Before my eyes, chunks of glass were transformed into gleaming repositories of history and memory, precious as the diamonds they mimic.

Yet I could not help but notice that Cornells work seemed at odds with its companions in the Surrealism gallery, to say nothing of the preceding parade of ambitious paintings and sculptures. The brutality of Andr Massons bloody fishes, battling amongst haphazard passages of sand and gesso; the startling juxtaposition of taxidermy parrot and mannequin leg in Joan Mirs Object (1936): these works seemed more concerned with shattering illusions than creating them.

I was not the first to observe Cornells incongruity with canonical narratives of Modern art. Deborah Solomons popular biography presents Cornell as a hermitic figure who, despite his engagement with New York City culture, remained ensconced in his mothers basement, lost in dreams. While sympathetic to the aims of these interpreters, I could not help but notice that these accounts remained structured by the dualistic oppositionsbetween belief and disbelief, ideal and realthat Cornell seemed determined to overcome. Taglionis Jewel Casket is after all an expression of the artists belief in the incantatory power of the aesthetic encounter. Cornell was also a lifelong practitioner of Christian Science, a religion devoted to mending what its followers perceive as the false divide between the material and the divine. Why, I wondered, was the price of Cornells modernity the abnegation of his most deeply held principles? How did belief become antithetical to intelligence and seriousness?

FIG. P.2 Installation view of the exhibition Painting and Sculpture: Inaugural Installation, November 20, 2004December 31, 2005, with Joseph Cornells Taglionis Jewel Casket at bottom left. Museum of Modern Art, New York.