Given current environmental concerns, it is not surprising to find literary critics and theorists surveying the Romantic poets with ecological hindsight. In this timely study, Onno Oerlemans extends these current ecocritical views by synthesizing a range of viewpoints from the Romantic period. He explores not only the ideas of poets and artists, but also those of philosophers, scientists, and explorers.

Oerlemans grounds his discussion in the works of specific Romantic authors, especially Wordsworth and Shelley, but also draws liberally on such fields as literary criticism, the philosophy of science, travel literature, environmentalist policy, art history, biology, geology, and genetics. He creates a fertile mix of historical analysis, cultural commentary, and close reading. Through this, we discover that the Romantics understood how they perceived the physical world, and how they distorted and abused it. Oerlemanss wide-ranging study adds much to our understanding of Romantic-period thinkers and thejr relationship to the natural world.

ONNO OERLEMANS is an associate professor at Hamilton College.

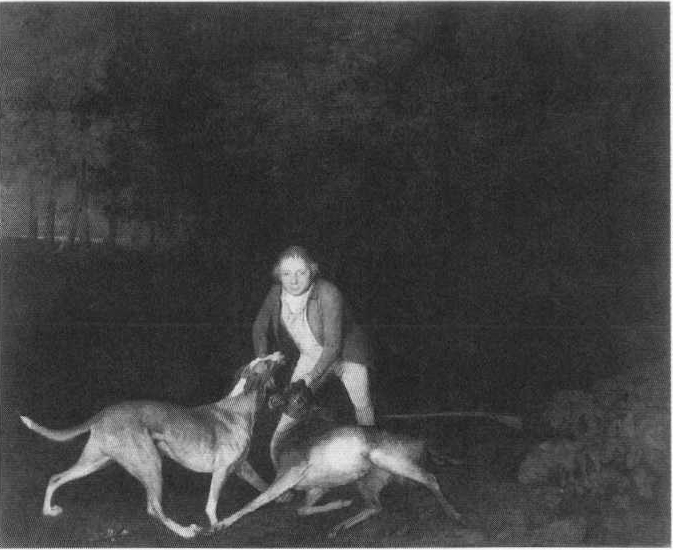

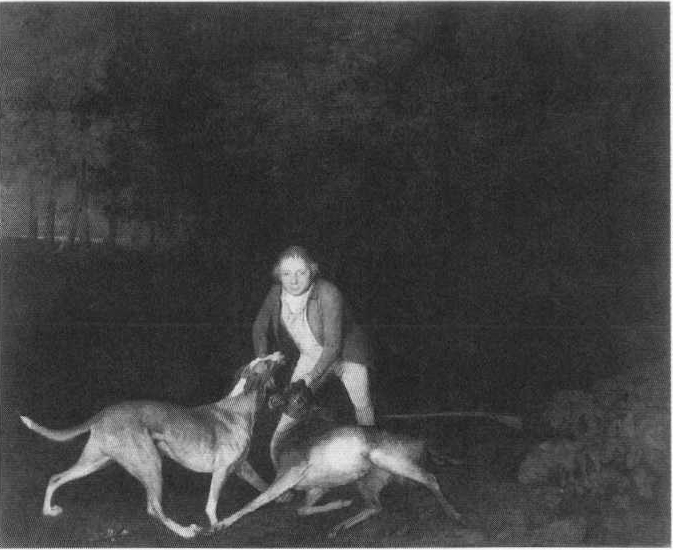

George Stubbs, 1724-1806. Freeman, the Earl of Clarendons gamekeeper, with a dying doe and hound. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

http://www.utppublishing.com

University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002

Toronto Buffalo London

Printed in Canada

Reprinted in papeback 2004

ISBN 0-8020-4863-3 (cloth)

ISBN 0-8020-8697-7 (paper)

Printed on acid-free paper

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Oerlemans, Onno, 1961

Romanticism and the materiality of nature

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8020-4863-3 (bound). - ISBN 0-8020-8697-7 (pbk.)

1. English literature - 19th century - History and criticism.

2. Nature in literature. 3. Romanticism - Great Britain. I. Title.

PR447.033 2002 820.93609034 C2001-902279-4

Cover illustration: Rocky Crag in the Harz Mountains, c. 1837/40; watercolour. Formerly collection of Friedrich August 11, Dresden.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council.

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP).

Introduction

Romanticism, Environmentalism, and the Material Sublime

I

The End of the World: Wordsworth, Nature, Elegy

II

The Meanest Thing That Feels: Anthropomorphizing Animals in Romanticism

III

Shelleys Ideal Body: Vegetarianism, Revolution, and Nature

IV

Romanticism and the Metaphysics of Classification

V

Moving through the Environment: Travel and Romanticism

Many people have helped me in the writing of this book. Paul Fry encouraged me to think about the possibilities of ecologically oriented criticism long before it was fashionable, and helped me to see that one could write critically about ones passions. James McKusick, Lawrence Buell, and Alan Bewell have been especially encouraging, and their books have been central in mapping the ground that I re-examine here. Jonathan Bates Romantic Ecology confirmed my sense I was doing something that mattered.

I am deeply thankful to Damhnait McHugh and Ina Ferris for reading portions of the manuscript, giving me valuable feedback, and forcing me to extend my research and knowledge. Steve Lukits provided much-needed trips to Round Lake, as well as bedrock perspectives on Wordsworth. Conversations with Mary Arseneau, April London, and Don Childs have kept me focused. The English Department at the University of Ottawa was a truly marvellous place to develop as a scholar and teacher. This book could not have been written without its collective support.

I also owe a significant debt to the editors. Suzanne Rancourt and Barbara Porter at the University of Toronto Press have helped see the manuscript to print. Judy Williams has done an impeccable job of helping me revise the text.

The University of Ottawa and Hamilton College provided funding for travel to do research at the British Library. A subvention for the publication of the book came from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada.

My final and greatest debt is to Sally Cockburn, for it is her form of passionate reasoning on matters moral and intellectual that has been my steady guide in writing the book. I dedicate it to her, with love.

Literary criticism of the past decade has begun to define clearly what many students of the romantic period have long assumed: that romanticism is an important origin for environmentalist thought. That many romantic-period writers expressed profound interest in the natural world has always been obvious. Their distinctive passion was marked by the rage for the picturesque tour, a pronounced interest in landscape painting, the celebration and detailed descriptions of natural settings, a seeming rejection-of the city and the culture it represented, as well as a notable interest in the physical sciences. We easily recognize too the influence of the setting of Rousseaus account of the love of Saint-Preux and Julie, Wordsworths descriptions of the Lake District, and Gilpins tours. The work of Jonathan Bate, Lawrence Buell, Alan Bewell, and Karl Kroeber has made explicit connections between romanticism and contemporary versions of the environmental imagination, in each case at least partially as an attempt to rescue romanticism from charges of political and moral apostasy made by new historicist critics in the 1980s. Jerome McGanns definition of romantic ideology as the apparent power of consciousness to recreate itself in apparent resistance to culture seemed to negate, or at least to make seriously suspicious, the romantic interest in nature. In reaction to the chorus of criticism McGann helped to initiate, Buell, for instance, argues that the willingness to admit that thick description of the external world can at least sometimes be a strong interest for writers and for readers, even when it also serves ulterior purposes, is particularly crucial in the case of the environmental text To give a sufficiently generous account of literatures environmental sensitivity, we need to find a way of conceiving the literal level that will neither peremptorily subordinate it nor gloss over its astigmatisms (90). It is this strong interest in the external world by writers of the romantic period that I examine, and attempt in part to define, throughout this book.

Next page