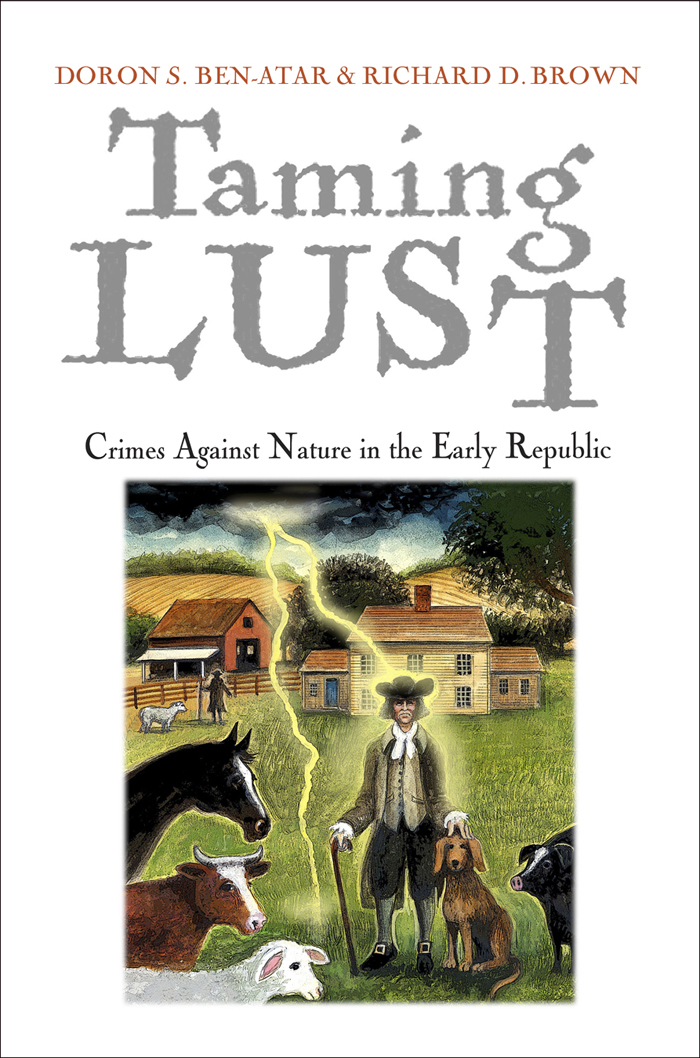

Taming Lust

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series editors:

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown,

Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial,

revolutionary, and early national history and culture,

Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes

and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character,

and with a special emphasis on the period from about

1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with

the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series

is available from the publisher.

TAMING

LUST

Crimes Against Nature in the Early Republic

DORON S. BEN-ATAR AND RICHARD D. BROWN

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2014 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used

for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this

book may be reproduced in any form by any means without

written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ben-Atar, Doron S.

Taming lust: crimes against nature in the early Republic /

Doron S. Ben-Atar and Richard D. Brown.1st ed.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4581-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. BestialityUnited StatesCase studies. 2. Bestiality

United StatesHistory18th century. 3. Criminal justice,

Administration ofUnited StatesHistory18th century.

4. United StatesCivilization18th century. I. Brown, Richard D.

II. Title. III. Series: Early American studies.

HQ71.5.B47B46 2014

306.0973dc23 2013033187

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Crimes Against Nature

This book treats a most unusual offenseone that evokes laughter for some and disgust in others. Our account of John Farrell and Gideon Washburn, two elderly New England men tried separately for bestiality in the 1790s, runs counter to the instinctual sense of what it means to be human, while also reminding us of the animalistic demons we hold in check. Researching and writing about bestiality, even reading this book, is an act of transgressionan affront, perhaps, to the good taste that seeks to keep the unseemly part of human existence hidden.

Prepare to be startled. Some of the analysis places cherished elements of Western culture in uneasy proximity to a despised practice. We point to elements in high art and religion where bestiality is part of both context and subtext. And our historical analysis necessitates consideration of bestiality as a subcategory of sodomya highly offensive association that might fuel homophobic prejudicebut one that is grounded in the statutory record. As far as the law in the early modern period was concerned, bestiality was a subcategory of sodomy. Even the enlightened philosopher Montesquieu spoke of bestiality and sodomy as one and the samecrimes against nature. Currently we associate sodomy with human anal penetration and male homosexuality. However, before the middle of the nineteenth century sodomy was a rather broad categorya catchall word that represented all nonreproductive sex as well as general moral degeneracy. A sodomite was a man who committed sexual acts prohibited in the Bible. Sodomy stood for the broader threat of sexual degeneracy. Finally, sodomy was the opposite of manlinessand all the gendered social and cultural associations that went with it.

Bestiality occupies an anomalous place in the range of sexual violations. It features elements similar to the two most abhorrent sexual crimes, rape

Bestiality has existed in every known human society.

Modern psychiatry has classified the phenomenon as zoophilia, a subcategory of paraphiliasexual desires or acts toward nonconsenting non-human subjects that involve suffering by one or both participants.

Bestiality comprehends a multitude of phenomena whose foundation in the physical world may never be quite clear. Its origin lies in the prohibition of sexual contact between man and beast, even though the boundaries between the lovingly humane and the sexually perverse are subjective

All through the autumn of 1796, eighty-five-year-old John Farrell, recently convicted by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court of engaging in a venereal affair with a certain female Brute Animal called a Bitch, wondered what his fate would be as he waited in the dank county jail at Northampton, Massachusetts. After Christmas, Farrell learned the worst. Governor Samuel Adams and the Governors Council had not only denied his latest petition for clemency but on December 26, 1796, the governor signed Farrells death warrant. The governor had given the order to the Hampshire County sheriff that in just a matter of weeks, on February 23, 1797, between the hours of Twelve and Three in the Afternoon, as punishment for the crime of Sodomy Farrell must be taken to the usual place of Execution, there to suffer the pains and penalties of Death. Prayer, it seemed, was Farrells only recourse. He could pray that the governor would, miraculously, change his mind; or, more realistically, he could pray that God would save his soul.

Almost exactly three years later, in the autumn of 1799, eighty-three-year-old Gideon Washburn, convicted of the same crime, was languishing in the Litchfield County, Connecticut, jailsome seventy miles southwest of where Farrell had been incarcerated. In a case that was wholly separate from Farrells, a Superior Court jury had decided on September 2, 1799, that the old man hath lain with beasts or brute Creatures by carnal copulation. In front of a crowded courtroom that probably included his wife and son, Judge Jesse Root declared he himself was smitten with horror and

John Farrell and Gideon Washburn were not sentenced to hang for bestiality in the seventeenth century, when Puritans prosecuted and executed witches, religious dissenters, and sexual offenders, but more than a century laterafter the American and French Revolutionsin the era known as the age of reason. By that time neither Massachusetts nor Connecticut had executed anyone for bestiality for at least 120 years. Yet suddenly, without warning, in the late 1790s and in villages in the same region, high courts determined that two old men would hang for the crime. Though the statutes were clear, there was no apparent social logic to these prosecutions. For even if the two elderly men did commit sexual acts with animals, bestiality did not seem to be a grave concern to people at the time. Indeed, despite Judge Roots expression of horror and amazement, few men who dwelled in late eighteenth-century New England could have reached middle age wholly ignorant of the reality that, forbidden or not, some boys and men did actually violate that barrier. Such knowledge might have come to them in barnyard and tavern gossip and jocular stories; or they might have known such misbehavior at first or second hand. But as Roots words convey, the fact that they were conscious of this particular human failing does not mean they accepted it or did not find such stories scandalous. We doubt that any householder would have questioned the language of Farrells and Washburns criminal indictments, which spoke of violations of the order of Nature; nor would they disagree with the judge who condemned the bestial act as a dishonor done to human nature. On the other hand, boys shared secrets and neighbors gossiped about what took place in barns and pastures; but only on rare occasions did authorities bring charges against offenders. Prosecuting ancient men for this offense was unknown.