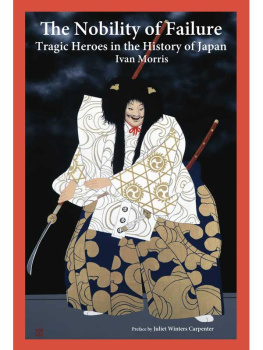

IVAN MORRIS

The World of the Shining Prince

Ivan Morris studied Japanese language and culture at Harvard University while serving in the Intelligence Section of the U.S. Navy Reserves. After receiving his Ph.D. from the University of London in 1951, he worked for the Far East Section of the BBC as well as for the Japan and Pacific departments of the British Foreign Office. He lived in Tokyo for several years, writing, lecturing, and teaching. In 1960 he joined what would later be renamed the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at Columbia University, where he served as department chair. He was elected a Fellow of St. Anthonys College at Oxford in 1966. Morris published numerous books on Japanese history, literature, and politics and produced distinguished translations of classical and contemporary Japanese works. He died in 1976.

OTHER BOOKS BY IVAN MORRIS

Readers Guide to Japan (1960)

Nationalism and the Right Wing in Japan (1960)

Japan 19311945 Militarism, Fascism, Japanism? (1963)

Dictionary of Selected Forms in Classical Japanese Literature (1966)

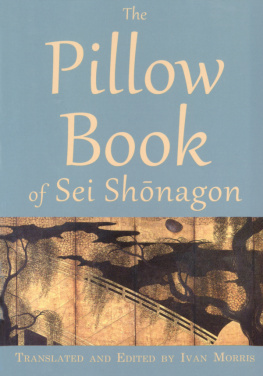

Companion to the Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon (1967)

The Riverside Puzzles (1969)

The Lonely Monk (1970)

Madly Singing in the Mountains: An Appreciation and Tribute to Arthur Waley (1970), Ivan Morris, editor

The Tale of Genji Scroll (1971)

The Nobility of Failure (1975)

TRANSLATIONS BY IVAN MORRIS

Fires on the Plain by Ooka Shohei (1957)

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Yukio Mishima (1959)

The Journey by Jiro Osaragi (1960)

The Life of an Amorous Woman and Other Writings by Ihara Saikaku (1961)

The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon (1961)

Thought and Behaviour in Modern Japanese Politics by Masao Maruyama (1963), Ivan Morris, editor.

As I Crossed a Bridge of Dreams by Lady Sarashima (1971)

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, MAY 2013

Copyright 1964 by Ivan Morris

Introduction copyright 1994 by Barbara Ruch

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in the United States by Kodansha America Inc. by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1994.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress.

eISBN: 978-0-345-80391-7

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

TO

Arthur Waley

CONTENTS

A PPENDIXES

INTRODUCTION

B ARBARA R UCH

Professor of Japanese Literature and Culture, Columbia University

Some books, few it is true, but some, belong to a genre all their own, and this is one of them. The World of the Shining Prince is named for the central figure in The Tale of Genji, one of the worlds greatest literary masterpieces, written by the eleventh-century Japanese genius, the court lady, Murasaki Shikibu. Morriss book is about neither the author nor her work, however, but rather deals with the cultural milieu that was the context for both. He has created here for Western readers a revelation of an age and a civilizationaristocratic life in Japan from about 9501050 CEone of the most unusual and engaging patterns that the kaleidoscope of history has produced.

I cannot think of another work, born in academia, that can so justifiably be described, as this one frequently was over the years, as enthralling. When first published in 1964, it won the prestigious Duff Cooper Award as the best book in the category of History / Biography published in England that year. Tens of thousands of copies have since been bought and read with fascination throughout the English-reading world, not only by students of Japan, but by novelists, poets, scholars of even vastly different fields of study, and by that indefinable book lover known as the general reader. It is truly a book to curl up with for many an evening of reading pleasure.

Almost ninety years have passed since Arthur Waleys brilliant translation of The Tale of Genji first appeared in England in 1925. Forty years later, with the appearance of Morriss The World of the Shining Prince, Waley himself confessed that he had long wished that someone would write just such a book as Ivan Morris has now produced, and expressed his joy that though nominally it is a book about the background of Genji in his generosity the author made it to some extent a book about the novel itself.

It was Virginia Woolf, however, who was surely the first to call publicly for just such a book. In her July 1925 review of the first volume of Waleys translation, her joy at having encountered for the first time a great woman writer heretofore totally unknownand one after her own heartis palpable. At last she has found a tradition of literature and a culture congenial to her tastes:

Perpetually fighting, now men, now swine our ancestors applied themselves to the pen or burst rudely and horsely into crude spasms of song. Meanwhile, at the same moment, on the other side of the globe the Lady Murasaki was looking out into her garden, and noticing how among the leaves were white flowers with petals half unfolded like lips of people smiling at their own thoughts.

She writes enviously of Lady Murasakis circumstances and moment in time where the accent of life did not fall upon war; the interests of men did not centre upon politics.In such an age as this Lady Murasaki could bring all her powers into play simultaneously.

Then, too, she recognized Murasakis point at once. To light up the many facets of his mind, Lady Murasaki, being herself a woman, naturally chose the medium of other womens minds. Aoi, Asagao, Fujitsubo, Murasaki, Yugao, Suyetsumuhana one after another they turn their clear or freakish light upon the gay young man at the centre.

Woolf then chides Waley for failing to quench her thirst for more about that court lady, about whom we know nothing, for Mr. Waley artfully withholds all information until the six volumes of her novel are before us.

Artfully or not, withhold he did; and that until was never to arrive.

One wishes that Virginia Woolf had lived to enjoy Ivan Morriss World of the Shining Prince. In our current age of cinema and satellite TV our images of Japan, though still desperately inadequate, are extraordinarily more sophisticated than they were when Waley first translated Genji. His audience had no store of visual imagery of Japanese apparel or architecture to call upon as they read. Waley thus had his court ladies in skirts, people would recline on cushions, throw open a casement window, or sit on a porch railing and chat. Despite these cultural compromises they seem an enormous improvement on those of Kench Suematsu, the young Japanese bureaucrat at Cambridge who, unknown to Waley, had published his translations of a few abbreviated chapters of the Genji in 1882 in which his ladies, in almost Grecian fashion, have wavy hair and wear thin silk tunics that show off their waists and figures.

In order to help Western readers of Waleys translation of The Tale of Genji understand the special world in which its author Murasaki Shikibu lived, as well as the fictional world of the Shining Prince Genji that she created, Morriss task was onerous. He had to overcome almost universal ignorance in the West concerning early Japanese civilization, specifically court life, but he also had to counter the weight of Victorian oppressiveness and censure that had often marred even those few scholarly books that preceded his. James Murdoch in his voluminous