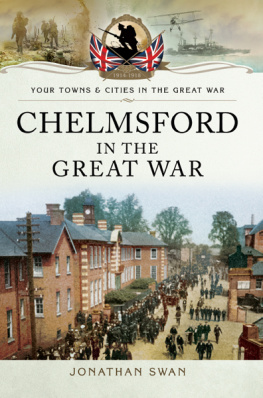

Law and War

Law and War

Magistrates in the Great War

Jonathan Swan

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Jonathan Swan 2017

ISBN 978 1 47385 337 9

eISBN 978 1 47385 338 6

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47385 339 3

The right of Jonathan Swan to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

To my wife, Rebecca, the fount of law and justice in the Swan household.

List of Plates

Bow Street police court. ( Essex Police Museum )

Bow Street police station. ( Essex Police Museum )

Court stamps. ( Authors collection )

Three years imprisonment cartoon. (Punch, 7 June 1916 )

Defence of the Realm poster. ( Authors collection )

Recruitment poster, Essex 1914. ( British Newspaper Archive )

Recruitment poster, 1914. ( British Newspaper Archive )

The Kings Proclamation, 4 August 1914. ( British Newspaper Archive )

Military legal system cartoon. ( Authors collection )

The grave of Private Wallace Williams. ( Melcome Regis Cemetery, Weymouth. Photograph by Sandie Sapsford )

Anti-German rioter cartoon. (Punch, 19 May 1915 )

Poster warning against giving drink to servicemen. ( British Newspaper Archive )

Government ale cartoon. ( Authors collection )

Nottingham lighting restrictions poster. ( British Newspaper Archive )

Diagram showing how to obscure motor vehicle headlights. ( British Newspaper Archive )

Lighting restrictions cartoon. (Punch, 1 December 1915 )

Policeman giving air raid warning. ( Essex Police Museum )

Poster appealing for skilled men for the Army Service Corps. ( British Newspaper Archive )

George Fromows exemption certificate. ( www.ancestry.co.uk )

Derby Scheme poster. ( Authors collection )

National Registration Act ID card. ( Authors collection )

List of deserters in the Police Gazette , 11 August 1914. ( British Newspaper Archive )

The Silver War Badge. ( Authors collection )

Reserved occupations poster. ( Authors collection )

Youth crime cartoon. (Punch, 5 September 1917 )

War Service badges. ( Authors collection )

Ministry of Food rationing breaches poster. ( Authors collection )

Shortage of matches cartoon. ( Authors collection )

Sugar rationing cartoon. (Punch, 24 January 1917 )

War Diary of 1 Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment. ( www.ancestry.co.uk )

Lance Corporal John Charles Lane. ( D\B\ta/42/17 Picture courtesy of Taunton Deane Borough Council and Somerset Heritage Centre. With kind permission of South West Heritage Trust )

Special constables cartoons. ( Authors collection and Punch, 14 October 1914 )

Captain Arthur Corbett Edwards. ( British Newspaper Archive )

Special Constable Herbert Gripper. ( British Newspaper Archive )

Captain Eugene Napoleon Ernest Mallett Vaughan. ( Authors collection )

Special constables warrant card. ( Essex Record Office )

Lieutenant Colonel Egerton Stanley Pipe Wolferstan. ( With kind permission of Tamworth Castle Museum [ 6817 ] ( 29/5576 ))

Preface

by His Honour Richard Seymour QC

In the summer of 1914 the British Government, legislators and the naval and military authorities realized that, for the first time in the history of the nation, it was going to be necessary for a high degree of legal regulation of activities in the United Kingdom to equip the country better to fight a war and to respond to the novel challenge of an enemy likely to be able to affect life in this country without necessarily invading. England had not been invaded successfully since 1066. There had been no serious threat of invasion for over a hundred years. No one, it seems, had given serious thought previously to what legal powers might be needed, and by whom, in the event that there was a threat of invasion or a need to compel citizens to collaborate in order effectively for the nation to be able to fight a war in Europe, still less throughout the world. Certainly there was no existing Parliamentary legislation in force which dealt with these matters, and no such legislation had ever been passed before. There were no precedents.

The first important legal question, as the likelihood of war increased in the summer of 1914, was not so much what laws to make, as how to make them. In other words, what powers of what body were to be used to make the new laws. There were, in principle, two possible sources of law-making power, the royal prerogative and Parliament. Another important question was whether either of these possible sources of law-making power permitted the delegation of law-making powers to someone else, and, if so, to whom and on what terms. Certainly, as things turned out, it was necessary for large numbers of regulations and orders dealing in detail with a vast range of matters to be produced, and often amended, speedily, and it was beyond the capacity of a legislative body to consider such a range of considerations and so much material as swiftly as was required. Unless much could be delegated, the making of the relevant laws could not be achieved. A further important issue was the mechanism by which whatever laws were made were to be enforced. That question involved considering what powers might be possessed by what authority to create new forms of court or tribunal.

Although very important in the period before Parliament established its present predominance as the source of new laws, and still important in some areas, the concept of the royal prerogative is difficult. Essentially it is the residue of the royal powers of the Norman kings, that is to say, what is left in the hands of the Crown (in modern times the Government, rather than the monarch personally), after centuries of Parliamentary development during which Parliament has progressively arrogated to itself power to intervene in ever-widening areas of national life. In 1914 it was unclear what limits, if any, there had been to the royal powers of the Norman kings, and the precise scope of what was left to the Crown was even less clear, save in well-established areas, such as foreign policy. As Parliament developed, it was accepted that Parliament could legislate, and thereby make law. However, although Parliament could change the English common law and limit the royal prerogative in any respects it chose, to the extent that Parliament did not choose to exercise that power, the English common law, including the royal prerogative, continued to be the law of the land. That remains the position today.