2021 by Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint

All rights reserved. Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8263-6249-0 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-8263-6250-6 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file

with the Library of Congress

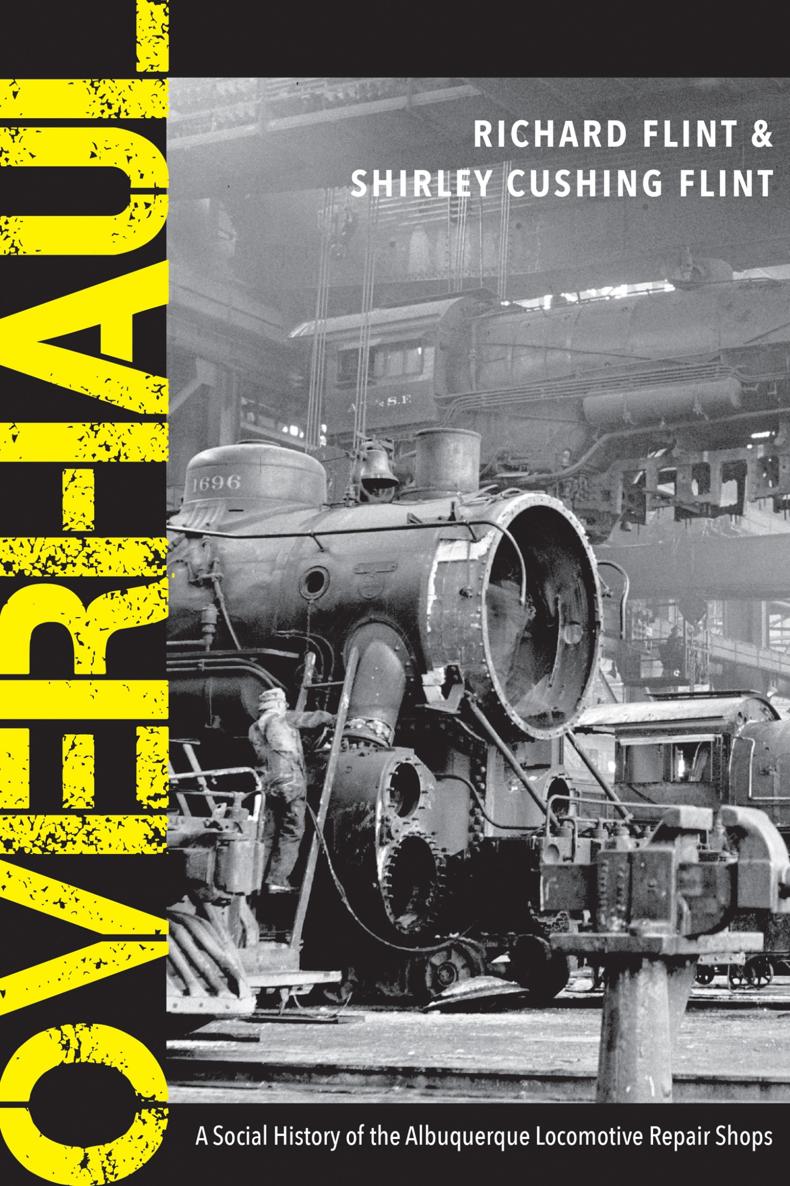

Cover photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress,

Prints and Photograph Division

Designed by Felicia Cedillos

Introduction

It has been more than sixty-five years since the last overhauled steam locomotive left an erecting bay at the Albuquerque Locomotive Repair Shops and returned to road service on the Santa Fe Railway. After the intervening years, marked by at least three human generations, only a few shopworkers remain who have firsthand memory of the painstaking work that went on at the Shopsand even secondhand memories are fading. Those dimming memories are often of huge neglected and decaying buildings: broken glass littering the ground and graffiti-tagged walls, interspersed with piles of junked metal and other debris.

Largely forgotten are the Shops heyday, the seventy-five years between 1880 and 1955, when the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway was far and away the largest employer in Albuquerque, paying solid, consistent wages that supported thriving middle-class communities on both sides of the Santa Fe main line to California. By the 1960s and 1970s, though, the barrios of Barelas (to the west) and San Jos (to the east) were rundown and in the process of abandonment. Urban renewal projects, designed to eradicate the blight but underfunded, left dilapidated buildings and gap-toothed cityscapes.

Fewer and fewer Albuquerqueans remember the blocks of well-kept houses and neat gardens that preceded the rundown barrios of the Shops district. Neither do they remember that steady railroad incomes of hundreds of families over generations established and solidified the middle-class status and expectations of thousands of workers and their families. Although not always as rosy as that sounds, the wages of many shopworkers raised their own and their childrens and grandchildrens positions in society to levels their forebears could only dream of.

Among the descendants of AT&SF shopmen and women whom we interviewed for this book, there are the mother of a US congresswoman, a former chief justice of the New Mexico Supreme Court, lawyers, teachers, engineers, successful and well-known businesspeople, popular sports figures, many college graduates, proud members in good standing of the Albuquerque and New Mexico communities, as well as more distant communities. As has been apparent from study of other US industrial-manufacturing cities, steady work and rising incomes from the late nineteenth century until the middle of the twentieth fostered widespread optimism and provided the wherewithal to realize many of the hopes and plans of AT&SF Shop families.

One of our primary objectives in writing Overhaul has been to lay out the reciprocal effects that the resident Hispanic and Native American population of the Middle Rio Grande Valley and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway have had on each other, both positive and negative. The extended encounter and accommodation of resident peoples with a major industry has strongly affected both. Albuquerques uniqueness among New Mexico communities arose and has been reinforced because of the coming and development of the AT&SF Locomotive Repair Shops.

Originally all but excluded from potential benefits of the overnight arrival of industrialization in their midst, Hispanos and Native Americans came to comprise the majority of skilled workers at the Shops by the mid-twentieth century. A very significant result of incorporation of large numbers of Hispanos and Native Americans into the skilled AT&SF workforce was the rise of a substantial and stable middle-class population in the Barelas and San Jos neighborhoods of Albuquerque. That middle-class population gradually expanded and spread to other areas of the city, the state, and the country. The effect on generations of descendants of AT&SF shopworkers has been transformational, a fact that we detail with many examples.

Like many other American industrial cities, Albuquerque suffered a serious, but not irreparable, blow when the major industry, in this case the Locomotive Repair Shops, closed in the 1970s. Albuquerque though, unlike many other industrially based cities, transitioned within just a few years into a financial and supply hub for oil, gas, and mining activity within the state, which boomed from the 1950s to the 1980s, and is currently experiencing another upsurge. Furthermore, Albuquerques economic base diversified through burgeoning involvement in atomic and alternative energy research and development; federal land management; support of tribal communities, higher education, and healthcare; manufacturing related to computerization and digitalization of many aspects of American life; and, most recently, as a film production and coordination center.

What started it all was establishment in the 1880s of a major steam locomotive repair facility and the foundation of modern Albuquerque. It is the story of the people, the place, and the work of the Shops that fills the pages of this book. The sources we used to compile that story range from interviews with former shopworkers and their descendants to photographs and site plans; from annual reports of the AT&SF Railway Company to contemporaneous newspaper accounts of daily happenings at the Shops; from meticulous studies by professional historians and social scientists to engineering specifications and manuals; from city directories and census data to architectural analyses; from the records of major strikes to payrolls for machinists and boilermakers; from reports of the US Geological Survey to issues of the Santa Fe Employees Magazine.

The point is that we have incorporated into Overhaul and have taken into account a wide range of sources in an effort to provide the most rounded and diverse view of what made up life and work in and around the Shops over its seventy-five-year lifespan. Overhaul is a record of many things that were once common knowledge to the residents of Albuquerque.

For decades, the city set its clocks and determined its rhythm by the steam whistle at the Shops. Everyone knew that the Shops were the clanging heart of Albuquerque. They set the city apart from its neighbors. From the beginning, they represented the energy and innovation that were driving modern life. The industrial virtuosity that was demonstrated by the best machinists produced a practical art that was second to none. Steam locomotivesgreat, black, clockwork machines that comprised intricate assemblages of thousands of matched and mated partsrequired the creative skilled labor of integrated teams of journeymen, apprentices, and helpers in a variety of crafts to overhaul and restore them periodically, and sometimes to rebuild them from the ground up. That work and the people who performed it are what we celebrate here.