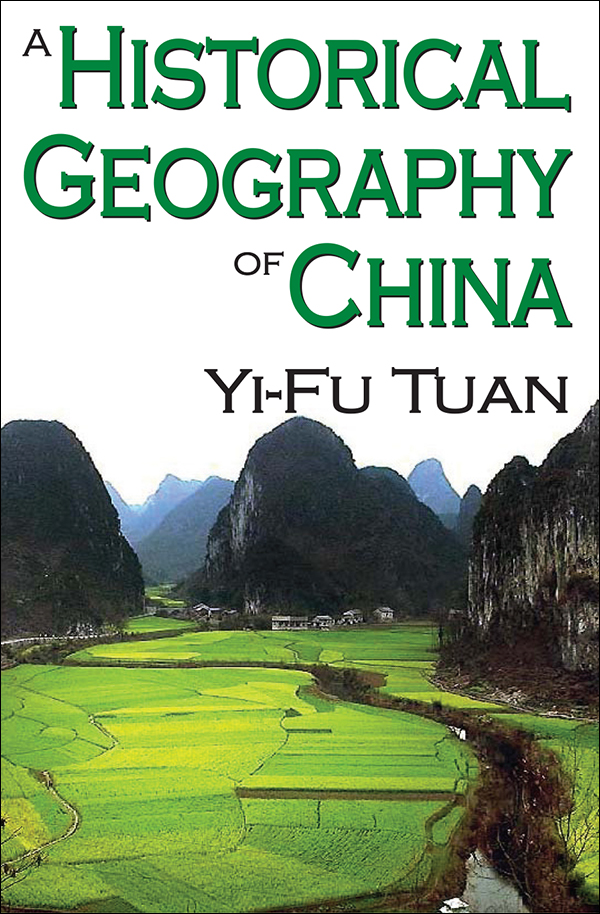

A H istorical

G eography

OF C hina

First published 2008 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2008002635

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tuan, Yi-fu, 1930-

[China.]

A historical geography of China / Yi-Fu Tuan.

p. cm.

Originally published under title: China. Chicago : Aldine Pub. Co., 1969,

in series: The worlds landscapes.

ISBN 978-0-202-36200-7 (alk. paper)

1. ChinaHistorical geography. I. Title.

DS706.5.T83 1969

915.1dc22

2008002635

ISBN 13: 978-0-202-36200-7(pbk)

Despite the multitude of geographical books that deal with differing areas of the world, no series has before attempted to explain mans role in moulding and changing its diverse landscapes. At the most there are books that study individual areas in detail, but usually in language too technical for the general reader. It is the purpose of this series to take regional geographical studies to the frontiers of contemporary research on the making of the Worlds landscapes. This is being done by specialists, each in his own area, yet in non-technical language that should appeal to both the general reader and to the discerning student.

We are leaving behind us an age that has viewed Nature as an objective reality. Today, we are living in a more pragmatic, less idealistic age. The nouns of previous thought forms are the verbs of a new outlook. Pure thought is being replaced by the use of knowledge for a technological society, busily engaged in changing the face of the earth. It is an age of operational thinking. The very functions of nature are being threatened by scientific take-overs, and it is not too fanciful to predict that the daily weather, the biological cycles of life processes, as well as the energy of the atom will become harnessed to human corporations. Thus it becomes imperative that all thoughtful citizens of our world today should know something of the changes man has already wrought in his physical habitat, and which he is now modifying with accelerating power.

Studies of mans impact on the landscapes of the earth are expanding rapidly. They involve diverse disciplines such as Quaternary sciences, archaeology, history and anthropology, with subjects that range from pollen analysis to plant domestication, field systems, settlement patterns and industrial land use. But with his sense of place, and his sympathy for synthesis, the geographer is well placed to handle this diversity of data in a meaningful manner: The appraisal of landscape changes, how and when man has altered and re-moulded the surface of the earth, is both pragmatic and interesting to a wide range of readers.

The concept of landscape is of course both concrete and elusive. In its Anglo-Saxon origin, landscipe referred to some unit of area that was a natural entity, such as the lands of a tribe or of a feudal lord. It was only at the end of the sixteenth century that, through the influence of Dutch landscape painters, the word also acquired the idea of a unit of visual perceptions, of a view. In the

German landschaft, both definitions have been maintained, a source of confusion and uncertainty in the use of the term. However, despite scholarly analysis of its ambiguity, the concept of landscape has increasing currency precisely because of its ambiguity. It refers to the total man-land complex in place and time, suggesting spatial interactions, and indicative of visual features that we can select, such as field and settlement patterns, set in the mosaics of relief, soils and vegetation. Thus the landscape is the point of reference in the selection of widely ranging data. It is the tangible context of mans association with the earth. It is the documentary evidence of the power of human perception to mould the resources of nature into human usage, a perception as varied as his cultures. Today, the ideological attitudes of man are being more dramatically imprinted on the earth than ever before, owing to technological capabilities.

In a book of this modest length, yet covering such extensive and intricate data, much could have been said that has necessarily been omitted. And as it is a pioneer work, the author has only touched in some fields that still await more research. Enough has been said in this work, however, to indicate that the Chinese landscapes are peculiarly the creation of the Chinese culture, indigenous and ancient. Yet, today, Communist China is a notable illustration of how the espousal of new social values can quickly alter the face of a whole nation. The countryside is being altered as dramatically as the cities, making the Chinese case of unique interest in its speed and scale of operation.

J. M. Houston

Contents

We are grateful to the following for permission to reproduce photographs:

Barnaby's Picture Library: Fig. 8; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mass.: Fig. 17; J. Allan Cash: Figs. 5, 11, 20, 27; Camera Press: Figs. 6, 26; Marc Riboud-Magnum: Figs. 2 and 30; Paul Popper Ltd.: Figs. 12, 13 and 15; Fig. 17 is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Fig. 16 is in the Collection of William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City; Figs. 3, 19, 22, 23, 29, 31, 32 and 33 are from photographs by the author.

The cover photograph is by kind permission of Marc Riboud.

Introduction

The Chinese earth is pervasively humanized through long occupation. Signs of man's presence vary from the obvious to the extremely subtle. The major changes that have been imposed on the country in the last two decades are obvious. The building of roads, bridges, dams, and factories, and the consolidation of farm holdings are altering the Chinese landscape before our eyes, and these alterations seem all the more conspicuous because they introduce features that are not distinctively Chinese. In contrast, traditional forms and architectural relics escape our attention because they are so identified with the Chinese scene that they appear to be almost outgrowths of nature. If this may be said of earth-coloured city walls, old pagodas and temples, it is even more true of rice fields and villages in the rural landscape. In viewing the densely packed areas such as the Canton delta, the Ssu-ch'uan basin, Chiang-su province, and parts of the North China plain, we need to make an effort of the imagination to see them as forests or marshes that have been slowly transformed through the centuries to the quintessential patterns of the traditional Chinese tapestry.

Even in the rugged parts of China, in areas which look like untouched wildernesses, subtle evidences of the human presence occur. Consider, for example, the landscapes depicted by Chinese artists. To the inexperienced eye they appear either unreal, the pictorial symbol of Taoist nature mysticism, or, if real, then the depiction of a remote nature that is devoid of artifice except for the retired scholar's hut. Yet to those who have seen more of China than her cities the paintings are no mere works of fantasy; they owe their expressive grammar at least in part to the special character of the Chinese environment. The physical setting of the Chinese differs from that of West Europeans and North Americans. Such topographic types as scarplands and vales, rounded hills and lowlands, and broad undulating plains are lacking in China. Most Chinese spend their lives on flat alluvial plains of varying size. On such young deposits even the hills, their lower flanks covered by rising alluvium, look like steepsided mountains. The tense contrast of the vertical and the horizontal, without the transitional zone of soft relief that characterizes the foothills, is a common trait of Chinese topography. In Kuei-chou province of southwestern China limestone spires stand vertically above small, flat plains. Nature here more than matches the seeming extravagance of art. In North China too, limestone and metamorphic rocks, such as those in the Ch'in-ling Mountains, provide sharp, dramatic relief. In South China, volcanic rocks weather into steepflanked mountains, their structural and topographic alignments camouflaged by intense stream erosion. As to the famous scenic areas, photographs of Hua Shan in southeastern Shen-hsi or Huang Shan in southern An-hui simulate classical paintings of the T'ang and Sung dynasties (Fig. 3).