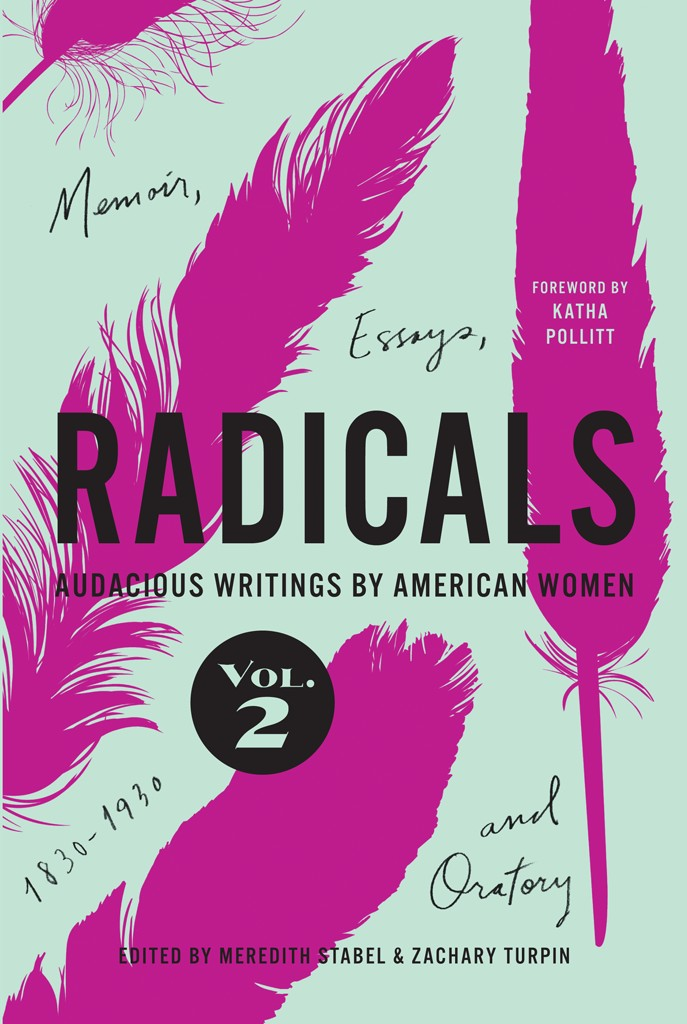

University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242

Copyright 2021 by the University of Iowa Press

Foreword copyright 2021 by Katha Pollitt

ISBN 978-1-60938-768-6 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-60938-769-3 (ebk)

www.uipress.uiowa.edu

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design by Kathleen Lynch / Black Kat Design Text design by April Leidig

No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach.

Printed on acid-free paper

Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress.

Foreword

The only nineteenth-century women I remember learning about in eighth-grade American history class were Dorothea Dix, who revolutionized treatment for the mentally ill, and Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross. Well, let me be fair. In high school English class, our teacher regaled us with the famous anecdote about Margaret Fullers announcing I accept the universe and Thomas Carlyles responding: By Gad, shed better. Im sure Susan B. Anthony was mentioned at some point. As for the great nineteenth-century struggles to which so many women devoted themselvesfor the vote, education, the abolition of slavery, rights for workers and married women, control of sexuality, access to professions and jobsyou could easily graduate from high school with all As and know very little about any of it. The vote, for example, was something women were granted, not the victorious culmination of a seventy-five-year-old battle waged by women themselves.

The 1970s womens movement, which gave rise to the revolutionary new field of womens history, changed all that. Today, most educated people know a bit about at least some of the major women in nineteenth-century American history: Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells-Barnett. There are scholarly studies, biographies, essays galore. As I write, a statue of Anthony, Stanton, and Truth is going up in Central Parkthe first to honor real-life women in that glorious and historic public space where up until now the only female statue was of Alice in Wonderland.

Youll find selections from the writings of many iconic women in this volume. Ida B. Wells-Barnett delivers an expos of lynching that still scorches, and the activist and educator Mary Church Terrell delivers another. Anna Julia Cooper boldly prefigures intersectionality: Only the BLACK WOMAN can say when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me. Emma Goldman vigorously attacks the institution of marriage: The institution of marriage makes a parasite of woman, an absolute dependent. It incapacitates her for lifes struggle, annihilates her social consciousness, paralyzes her imagination, and then imposes its gracious protection, which is in reality a snare, a travesty on human character.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, today most famous for her short story The Yellow Wall-paper, in which a woman is driven insane by her oppressive marriage, was far better known in her day as a prolific journalist and economist. Her argument that employment for women, especially mothers, was key to their liberation is still a controversial claim (e.g., Mommy Wars): Women; wives and mothers; are becoming a permanent half of the world workers. In their interest we shall inevitably change the brutal and foolish hardships now surrounding labor into such decent and healthful conditions as shall be no injury to any one. That children should be forced to work for their livings is an unnatural outrage, wholly injurious. That adult women should do it, is in no way harmful, if the hours and conditions of labor are suitable; and they never will be made suitable until overwhelming numbers of working women compel them (Maternity Benefits and Reformers). Gilmans optimism is typical of the women collected in Radicals, as of so many nineteenth-century figures. The questions might be difficult, but the answers tended to be simple. What would Gilman make of the fact that most mothers are in the workforce today but we are still waiting for those suitable working conditions? Similarly, many suffragists thought suffrage was not just a right that belonged to women as citizens; they also believed womens votes would transform the nation: women would purify the public realm as they purified the home and ensure honest, responsible government and the protection of women and children. It turned out to be a lot more complicated than that. For decades after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, women who could vote were less likely to vote than men, and when they did vote, they often voted like their husbands. Curiously, the major electoral victory of women until almost our own day was achieved before most women could cast a ballot. That would be Prohibition, the Eighteenth Amendment, the culmination of a crusade begun decades before by the formidable Frances Willard, tireless head of the Womans Christian Temperance Union. Willards separate spheres ideology sounds terribly antiquated today and not very feminist, but in an age in which middle-class white women were firmly confined to the home, it was rather clever to turn domesticity into a power base for public actionour great home cause.

The nineteenth century was violent and grim. Black people were enslaved and then forced into subjection. Native Americans were driven off their land, their children sent to boarding schools that sought to extirpate their culture. Millions of women were trapped in desperate poverty, domestic violence, low-wage employment, without even the right to custody of their own children. This collection reminds us that it was also a time of great social and intellectual excitement. Feminism was brewing in surprising places: Frances Willard found liberation in learning to ride a bicycle. Religious women demanded a wider role as church workers, missionaries, and even preachers. Christianity itself could be bent to feminist uses. And how came Jesus into the world? asks Sojourner Truth in her speech to the Womens Rights Convention in 1851. Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part?

The shortcomings of nineteenth-century feminists are obvious to us today. Some were racists and some were suspiciously eager to control population and improve society through sterilization. Gilman in particular had a penchant for taking a sensible idea much too far. An essay that begins in support of rational suicide (she herself committed suicide when her terminal cancer became unbearable) ends up calling for widespread capital punishment and killing off the old and sick. Its worth remembering, though, that racism, classism, eugenics, nativism, hostility to non-Christian religions and cultures, and a penchant for sweeping solutions and quick fixes were not unique to feminists. They were common features of the progressive thought of the era.