First published 1992

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk .

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

a division of Routledge, Chapman and Hall Inc.

29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

1992 Gail Holst-Warhaft

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Holst-Warhaft, Gail

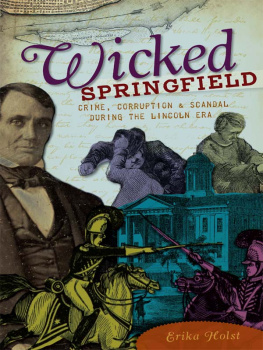

Dangerous voices: womens laments and Greek literature.

I. Title

393.9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Holst-Warhaft, Gail,

Dangerous voices: womens laments and Greek literature/by Gail Holst-Warhaft.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Greek literatureHistory and criticism. Literature

and SocietyGreeceHistory. Women and literature

GreeceHistory. Mourning customsGreeceHistory.

WomenGreeceSocial conditions. Mourning customs in literature. LamentsGreece

History.

Laments in literature. Death in literature.

I. Title.

PA3074.H64 1992

880.9'001'089dc20 9140115

ISBN 0-203-04101-1 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-203-20355-0 (Adobe eReader Format)

ISBN 0-415-07249-2 (Print Edition)

For my son, Sacha Ambrose Warhaft, January 1985October 1988

my little ear of wheat, winnowed and reaped unripe

(Greek lament)

Acknowledgements

Part of the contents of chapter 6 appeared in the Journal of Modern Greek Studies, October 1991. I am grateful to the editors for permission to use the material in this book.

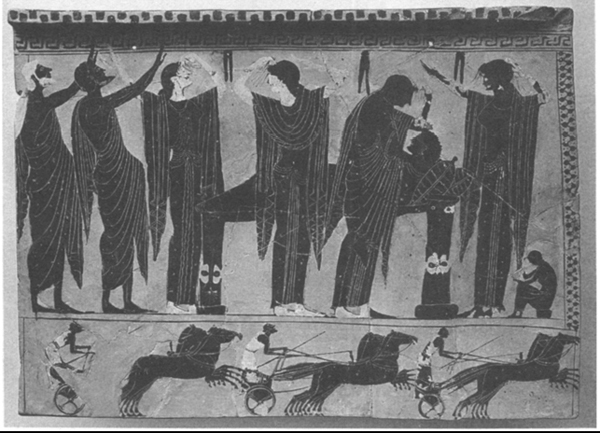

The frontispiece was reproduced by kind permission of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1954.

I thank all my friends and colleagues who have given me material, discussed my work with me and offered their insights. They include Fred Ahl, Martin Bernal, Wayles Browne, Calum Carmichael, Sotiris Chianis, John Chioles, David Curzon, Vangelis Fambas, Steven Feld, Helene Foley, Sandor Goodhart, David Grossvogel, Janet Hart, Rudolf Kser, Lucia Lermond, Jean Lewis, David McCann, Kathryn March, Philip Mitsis, Charina and Francis Oeser, Jeff Rusten, Marcia and Barry Strauss, Karen Van Dyck, Kostas Vantzos, Ingeborg Wald and Olga Zissi. The Western Societies Program at Cornell University, under the imaginative guidance of Susan Tarrow and Sander Gilman, provided me with travel and study grants to complete my research.

I particularly want to thank three of my dear friends: Chana Kronfeld, whose painstaking criticism and encouragement helped me structure my own lament; Margaret Alexiou, whose work on lament was in large part the inspiration for this study and who gave my manuscript a generous, insightful reading; and Mariza Koch, who taught me how Greek women turn tears into ideas.

Zellman, Zoe and Simon helped put an end to laments.

A note on transliteration and translation

For some reason, the question of transliteration seems to arouse more angry debate than almost any other issue in Greek studies. I apologize in advance for having adopted what seemed to me to be a useful working compromise. Rather than attempt to abide by a strict system of transliteration that approximated modern Greek pronunciation for Greek words, I have tried to follow generally acceptable English practice based on the spelling of the original Greek or on common usage. This means that I have used moiroli rather than miroloy, epitaphios rather than epitfios . Similarly I have used Maniot rather than Maniat (see Seremetakis 1991) because books like Patrick Leigh-Fermors Mani have made the former familiar to the English reader. Unless otherwise acknowledged, translations of ancient and modern Greek texts are my own and I bear full responsibility for them.

Introduction

Dangerous voices: womens laments and Greek literature

Mourning is universal, its rituals manifold. Among them, one of the most interesting and least understood is lament. When we speak of lament, we are speaking of many different genres. A lament is an expression of mourning, but it is not necessarily mourning for the dead. A whole class of laments, including those of the biblical book of Lamentations, are songs for the fall of great cities. In cultures where forced emigration is common, we often find laments either for those who have gone into exile or composed by migrs for the homeland and family they have left behind. In Finland, China and Greece, laments are sung by the brides family, and often by the bride herself, as she leaves to become a member of her husbands household.

The form laments take is just as varied as their subject. Anything from an elaborate poem to tuneful weeping can be classified as a lament. In this investigation I am particularly interested in laments for the dead, and since the two cultures I will be looking at closely are ancient and modern Greece, I will be looking at a variety of forms of lament, from the kommos of classical tragedy to the folk laments of Mani and Epirus.

LAMENT AS AN ART OF WOMEN

What is common to laments for the dead in most traditional cultures is that they are part of more elaborate rituals for the dead, and that they are usually performed by women. In these cultures, as in our own, women and men are perceived and expected to mourn in different ways. Men and women may both weep for their dead, but it is women who tend to weep longer, louder, and it is they who are thought to communicate directly with the dead through their wailing songs. Frequently, in these cultures, laments are led or sung by a skilled, even professional class of women who are regarded as being especially gifted at improvising and performing songs for the dead. There is evidence, even in traditional societies, that it is more shameful for men to weep over their dead than women. When we come to lament as a western literary genre written mostly by men, we are reminded that women and men mourn in their own ways,and that while in early literary texts such as the Bible and the Homeric poems it was proper for men to weep and be wept over, it later became unacceptable:

There our murdered brother lies;

Wake him not with womens cries;

Mourn the way that manhood ought

Sit in silent trance of thought.