Copyright 2016 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

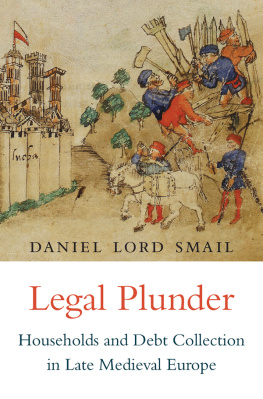

Jacket art: Detail from Giovanni Sercambi, Croniche, early 15th century. Archivio di Stato di Lucca, Biblioteca Manoscritti, n. 107, fol. 296r. By license of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attivit Culturali. Authorized by protocol no. 2297, 30 Sept. 2015. This image may not be subsequently copied or reproduced in any format.

Jacket design: Annamarie McMahon Why

978-0-674-73728-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

978-0-674-97012-0 (EPUB)

978-0-674-97011-3 (MOBI)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Smail, Daniel Lord, author.

Title: Legal plunder : households and debt collection in late medieval Europe / Daniel Lord Smail.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015041058

Subjects: LCSH: DebtItalyLuccaHistoryTo 1500. | Collecting of accountsItalyLuccaHistoryTo 1500. | Material cultureItalyLuccaHistoryTo 1500. | DebtFranceMarseilleHistoryTo 1500. | Collecting of accountsFranceMarseilleHistoryTo 1500. | Material cultureFranceMarseilleHistoryTo 1500. | EuropeEconomic conditionsTo 1492.

Classification: LCC HG3701 .S5896 2016 | DDC 332.1/753dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041058

THE theme of this book materialized while I was in the Archivio di Stato di Lucca doing preliminary work for a different project. My research had hitherto focused almost entirely on the southern French city of Marseille, but I turned to Lucca in 2007 when I began to feelmistakenly, as it turned outthat I was no longer learning new things from the archives of Marseille, and that it was time to try something else. In Lucca, I expected to study witness testimony, and certainly there is plenty of that in the court records. But I also came across a series of records related to debt collection, a kind of documentation that is not common in Marseilles medieval archives, as I knew from having written a short and speculative article on the subject. The records caught my eye not just because of their volume but also because of my growing interest in materiality. This interest originally sprang from the birds-eye reading I had done on the history of consumption for my 2003 book The Consumption of Justice, where I tried to argue that people consumed legal services, notably litigation, for much the same reason that they purchased really nice clothes, namely, to make an impression and to compete for social distinction. But here, arrayed before me, was a different and more tangible kind of materiality, as revealed in entry after entry in the judicial records of the Podest di Lucca and other courts, thousands of entries in all, that listed the objects seized in plunder from the houses of debtors for repayment of debt. So I abandoned the project that had brought me to Lucca in the first place and launched into this new theme, little knowing at the time that it would take a number of years to get this far, which is not very far at all. The problem, quite apart from the wealth of the Italian archival material, is that the subject of debt collection touches on many different literatures: the history and anthropology of things, systems of credit and debt, and, where the Lucchesia is concerned, the agrarian structures of the Tuscan economy. It is not easy to master any of these subjects, let alone bring them together, given how cultural, social, and economic histories tend to pull in different directions.

The richness of the Lucchese material took me back to Marseille, where I gathered together other evidence regarding household things and patterns of debt collection that I had more or less passed over in my previous work. In the case of the things that are so often mentioned in records from this period, I had passed them over partly because the vocabulary of material culture is very regional and thoroughly obscure. After all, what exactly is a spasotum? Or, for that matter, a set of crenculi? The latter word has continued to defy my attempts to track down its meaning. As a social and legal historian more at ease with court records and serial documentation, I am not especially well equipped for this kind of work, and although many of the words have now become clear to meI now know what a spasotum isthere remain significant gaps that require the attention of people with robust philological and archaeological skills. But the records themselves, laconic and spare though they may be in their narratives, are captivating for the insights they offer on patterns of everyday life. It is a wondrous thing to be able to tag along vicariously with a sergeant of the court as he enters an establishment in the city of Lucca in 1342 and takes, of all things, unam piastram sive lapidem ad otturandum buccham furni: a slab or a stone for closing off the mouth of an oven (Archivio di Stato di Lucca, Podestdi Lucca 116, fol. 71r). As we contemplate this act of plunder by a medieval repo manthis was one of three oven doors seized from the same hapless potter by three different creditors over a period of ten days in November of that yearquestions spring effortlessly to mind. Why on earth did the sergeant take an oven door? What did the creditor think when the sergeant presented him with an oven door rather than something more fungible, and lighter, such as a coverlet or a tunic, or, for that matter, a purse full of money? Although an oven door was not nearly as common a target of seizure as a wine cask or a tunic, the fact that it appears at all needs just as much explaining as the thousands of casks and the hundreds of tunics that appear in the small collection that I have assembled for this project.

In these days, when studies of material culture often seem to veer toward the desiring subject who is constantly in pursuit of nice things, it may seem odd to write a book that considers not just the status objects but the everyday objects and the shabby things as well. There is plenty of precedent for this, in the work of scholars such as James Deetz, the pioneering American archaeologist of small and forgotten things, and Daniel Roche, the great early modern French historian of everyday things, not to mention the work of antiquarians and experts on everyday life in medieval Europe that goes back more than a century. In the hope that some readers will feel, as I do, that desire and status have been given their due, and that in these times of growing wealth inequality, it is more important than ever to think about poverty, I have chosen to give subaltern objects a chance to speak for themselves, according them just as much attention as the fancy stuff. The objects featured in this book, many of which are suitably shabby, are set off typographically by means of bulleted lists so that the reader can appreciate the materiality described in the record more directly. I have rendered these lists in English translation but have at times provided the original Latin, Provenal, and Tuscan, in some cases for the time-honored reason that scholars will want to form their own opinions regarding doubtful translations, in others because the words themselves are beautiful and redolent of the world of which they were a part, and occasionally because, despite my best efforts at transcription and translation, there are many words that still baffle me.