Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

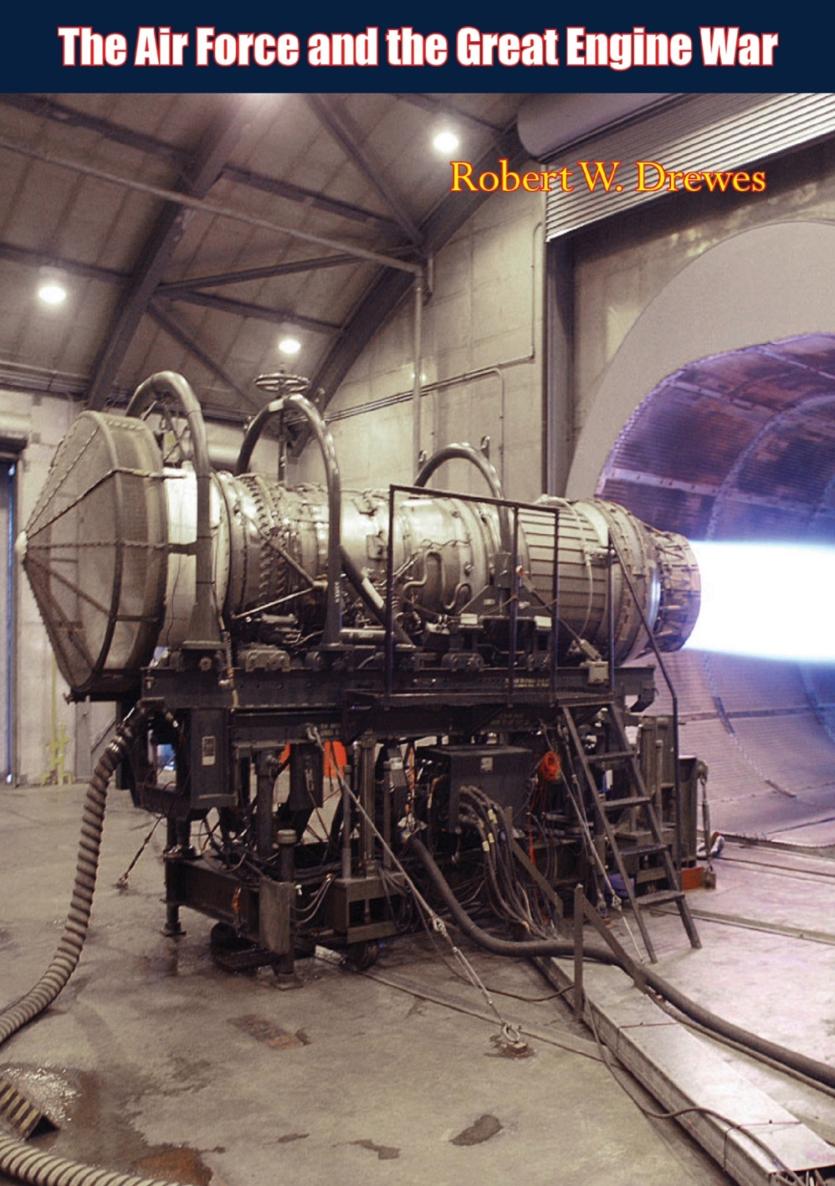

THE AIR FORCE AND THE GREAT ENGINE WAR

BY

ROBERT W. DREWES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

FOREWORD

HIGHLY PUBLICIZED ACCOUNTS of abuse in military weapons procurement have raised both citizen awareness of and citizen concern with the properly monitored spending of US defense dollars. Not long ago, media reports of spare parts overpricing and related problems ignited harsh public criticism of the handling of the multibillion dollar defense contracts for the F100 jet engine. According to Colonel Robert Drewes, US Air Force, though, the outcome of the subsequent Great Engine War calls not for criticism, but for praise for the Department of Defense.

Long before the public became aware of the controversy, the Air Force was grappling with the problems of the F100 high performance engine and the contract for its procurement and maintenance. As difficulties mounted in negotiations with the sole-source supplier, the Air Force, Navy, and Congress held their ground and eventually prevailed. The account of their combined efforts is an encouraging story about the Department of Defense and the US Government setting things right, a story that has not been fully told before.

The case is not closed on jet engine contracting, or any other kind of defense contracting, but the Great Engine War is welcome reassurance that US defense dollarsclosely monitoredwill be spent wisely.

Bradley C. Hosmer

Lieutenant-General, US Air Force

President, National Defense University

PREFACE

I WROTE THIS BOOK because the telling of these events is overdue. In the midst of barrages of criticism of how the military does business, someone had to tell a different story, a story in which, at least for the moment, the Air Force can take pride. Whether the pride can endure depends on how well additional gains are made with the opportunities now available.

The story focuses on the complex considerations and interactions which permeate every step in bringing a major weapon system from a mental image to the drawing board, to production, and on to operational use. Along the way the work is saturated with incessant concerns over congressional actions, inter-Service rivalry, inter-staff squabbles, and contractor posturing as well as hard-core problems with the technology. The objective of this book is to demonstrate how individuals working in an environment of seemingly endless distractions and frustrations can still have a vision of what makes sense and persist in making the ideal a reality.

Initially this book was to concentrate only on the events beginning in the early 1980s when the Air Force started bringing General Electric and Pratt and Whitney together again in a head-to-head competition for future requirements. However, as research progressed it became clear that to appreciate the significance of this formal competition, the earlier struggles with the engine and mounting emotional intensity must be understood as well. Furthermore, the message must also be conveyed that the problem engine, the F100 built by Pratt, is, nevertheless, a marvelous machine. Gene Bryant, the Air Force F100 program manager, explains that people have asked a lot of the engine and it has given a lot. {1} General Bellis, who managed the concurrent development of the F-15 fighter and the F100 engine, states, Over the 15 years since we started the F100 development program, it still is the highest performing engine in the world with corresponding fuel efficiencies. It has a better operational record in the USAF inventory than any other fighter engine. {2} Therefore, in telling the story I have tried to include the many positive aspects of the engines performance.

Likewise, this story is not intended to castigate a particular contractor. Specific problems arose, individuals reacted in certain ways, miscommunications occurred, and in retrospect, it seems easy to see how situations could have been handled better. But, to identify these problems is not to categorically denounce a contractor or a project. Certainly, such is not my intention. Events occurring in times past do not necessarily portend how individuals or institutions will face future challenges.

I wish to gratefully recognize Major-General Bernard Weiss for his suggestions in launching the research in this topic. Special recognition is owed as well to Dean Gissendanner and Tack Nix at the Pentagon, Ron Mutzelburg at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, and Nick Constantine, enjoying retirement in Alexandria, Virginia, for their always thoughtful insights and assistance with this story. In addition, the comments from Generals Bellis and Slay were especially valued. Furthermore, at a key juncture in my research, Professor Herm Stekler of the Industrial College of the Armed Forces faculty wisely suggested additional productive sources for background information on the contractors.

Most important, all of my hundreds of hours of interviews and examinations of documents would have been wasted without the professional assistance of the National Defense University Research and Publication Directorate.

R.W.D.

INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK examines the Great Engine War, referred to by Secretary of the Air Force Verne Orr in 1984 as perhaps the most significant Air Force acquisition initiative in the past decade. {3} The war pitted Pratt and Whitney Aircraft (part of the United Technologies conglomerate) against General Electric in head-to-head competition for multibillion dollar defense contracts to provide high performance engines for the nations frontline fighter aircraft. Throughout the war, from early skirmishes as each firm maneuvered into position, through periods of behind-the-scenes planning, to the outcome of the official competition in 1984, the Air Force duelled constantly with the contractors and ultimately set the rules of engagement for the biggest battle of all, thus far.

More than 10 years after the Air Force decided Pratt had won the competition against General Electric to develop and manufacture the F100 engine for the F-X, the Air Force changed its mind and reopened engine competition. After receiving thousands of engines from Pratt, the Air Force set out to find a better deal for the remaining billions of dollars of engines still required. Why?

Historically, after a defense contractor had competed and won a contract to design, develop, and produce any portion of a major weapon system (such as the engine), he was virtually assured (through operation of the marketplace) of receiving all follow-on business for the product without competing again. Determination by economics usually guarantees this sole-source, non-competitive position. The costs incurred to design a competitive product, to set up a production line, to provide an experienced labor force, and to establish the field service that supports operational use of a product usually preclude a profit-motivated business from submitting a new competitive proposal.