2010 THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS

All rights reserved

Designed and set by Kimberly Bryant in Miller and Gotham types.

Manufactured in Singapore

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

When Janey comes marching home : portraits of women combat veterans / [collected by] Laura Browder;

photographs by Sascha Pflaeging.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8078-3380-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Women veteransUnited StatesBiography. 2. Women veteransUnited StatesPictorial works. 3. United StatesArmed ForcesWomenBiography. 4. United StatesArmed ForcesWomenPictorial works. 5. Iraq War, 2003WomenUnited StatesBiography. 6. Afghan War, 2001WomenUnited StatesBiography. 7. Iraq War, 2003Personal narratives, American. 8. Afghan War, 2003Personal narratives, American. 9. Women and warUnited States. I. Browder, Laura, 1963 II. Pflaeging, Sascha.

U52.W475 2010

956.704434092273dc22 2009039271

Portions of this book originally appeared in the Virginia Quarterly Review.

14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

Introduction

The first time I heard a woman describe her deployment in glowing terms, I was taken aback. Marine Colonel Jenny Holbert told me that being in charge of public affairs for the second battle of Fallujah was probably one of the biggest events of my life, other than birthing two children. I thought, cynically, that this enthusiasm was all part of her role as a public affairs officer. It took me a while to understand how compelling the experience of being in a combat zone could be for the women I talked with.

Colonel Holberts enthusiasm for deployment was only one of many surprises I encountered over the course of the fifty-two interviews I did with women soldiers, sailors, coasties, airmen, and marines across the eastern seaboard. Originally, photographer Sascha Pflaeging and I had conceived of our collaboration as a way of hearing the stories and showing the faces of some of the first large cohort of womenover 221,000 as of this writingwho had served in the American military in Iraq, Afghanistan, and surrounding regions.

This is a far greater number than have served in any previous war in which the American military was deployed. Although a handful of women served in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, they had to cross-dress to do so. The 35,000 women deployed in War World I worked mainly as telephone operators and in other positions far from the front lines. Although almost 400,000 served in World War II, mostly in the Army and Navy Auxiliary Corps (WAC and WAVES), these women were barred from wielding weapons. The 7,500 women who were deployed in the Vietnam War served primarily as nurses.

However, the changes in the American military over the last several decades, including the end of the draft in 1973 and the beginning of the all-volunteer force, have dramatically increased both the number of women assigned to combat zones and their roles there. The Coast Guard Academy enrolled its first cohort of women in 1975, and the other service academies followed suit the following year. In 1993, Secretary of Defense Les Aspin directed the armed services to open up combat aviation jobs for women, and directed the navy to draft legislation repealing the combat ship exclusion. The following year, the Department of Defense Risk Rule, which closed many combat support positions to women, was rescinded, and 32,700 army positions and 48,000 Marine Corps positions were subsequently opened to women.

The current wars are providing a vastly larger number of women than ever before with the opportunity and the obligation to serve in combat zones. Before 1973, women made up less than 2 percent of the U.S. military. According to the U.S. Census, the U.S. military is now 14 percent female.

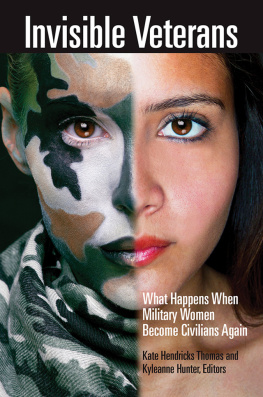

This project first took the form of a gallery exhibition. Ashley Kistler, the curator of our show at the Visual Arts Center of Richmond, encouraged us to think expansively about our work. We planned on creating forty large-scale color photographic prints, each paired with a narrative panel in the portrait subjects own words. Saschas photographs, we thought, would be a means of exploring a new genre of war photography. Although soldiers have long been the subjects of documentary photographs, it is rare that the public has seen images of women who have experienced combat. War photography has traditionally focused on men as heroes and aggressors and on women and children as victims. Photographs of wounded soldiers who are mothers could have the power to unsettle our fixed ideas about Americans at war, and their narratives could add dimension to the often flawed or fragmentary representations of women soldiers in popular culture: they too often appear as novelties, not as real soldiers.

From a civilian perspective, the Iraq War would seem to be a horrific experience, with its improvised explosive devices (IEDs), long deployments, and resulting high incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). (Bill Nash, a marine psychiatrist I spoke with, said that the military was anticipating higher rates of PTSD than came out of the Vietnam War.) The experience of being taken away from loved ones for up to fifteen months at a time must have been nearly unendurable for many who served. And surely there were some members of the military who did not believe that this was a war we should have been fighting. How then could they return to Iraq or Afghanistan for deployment after deployment? For women soldiers, we might imagine such deployments as particularly difficult, especially given the recent studies citing the high incidence of rape and sexual harassment in the military. These were our thoughts and expectations going into the project. We did not yet know how the women we interviewed would see their own experience.

There were a few common themes that emerged in all of the interviews I did, though predictably, the soldiers responses were as varied as the women themselves. One issue that came up repeatedly was motherhood. Police Captain Odetta Johnson, an army reservist, still regretted that she had had to cut her deployment a month or two short in order to return to her young son, who was facing surgery. She described her familys pressure on her to come back and her disappointment at letting down the members of her unit. As Marine Sergeant Jocelyn Proano said, You want to be a marine, and you cant be a mom all the time. Sergeant Proano, who joined the military after being expelled from high school, talked about getting her deployment orders when her daughter had just turned one: That was the worst everto leave my kid and everything. Yet she found her feelings for her daughter were in conflict with her military training: The mommy mentality left me as soon as we got on that bus and started flying to Cherry Point. Proano ended up extending her six-month deployment so that she would not have to leave her unit. Single mother Lieutenant Colonel Willa Townes, U.S. Army Reserve, now retired, was deployed when her son was four. She had the choice of not going, because she had no family member who could take the child. But she was determined to serve in Iraq and finally got her sons daycare provider to board him for the year, to her great relief.