E

VEN A LONGTIME MANHATTANITE IS LIKELY TO SUFFER THE

same geographical disorientation as a first-time visitor from time

to time. When that happens, it can be surprisingly easyone

might say democraticto correct ones internal GPS and quickly

find a way to get from point A to point Z. Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx,

and Staten Island are mazes of streets, terraces, courts, plazas, boulevards,

and culs-de-sac that defeat logical maneuvering; Manhattans street grid

is a wayfinding marvel. Aside from the quaint historic winding lanes,

hidden cobblestone alleys, and converging intersections typical of vintage

downtown Manhattan, most (but not all) of the borough was planned

on such a rational formula, with numbered streets crossed by numbered

(more or less) avenues, that getting around can be as simple as reading

a street sign.

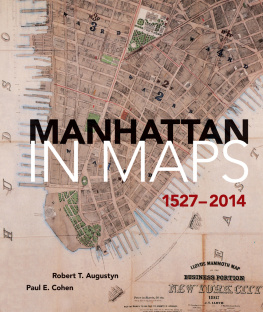

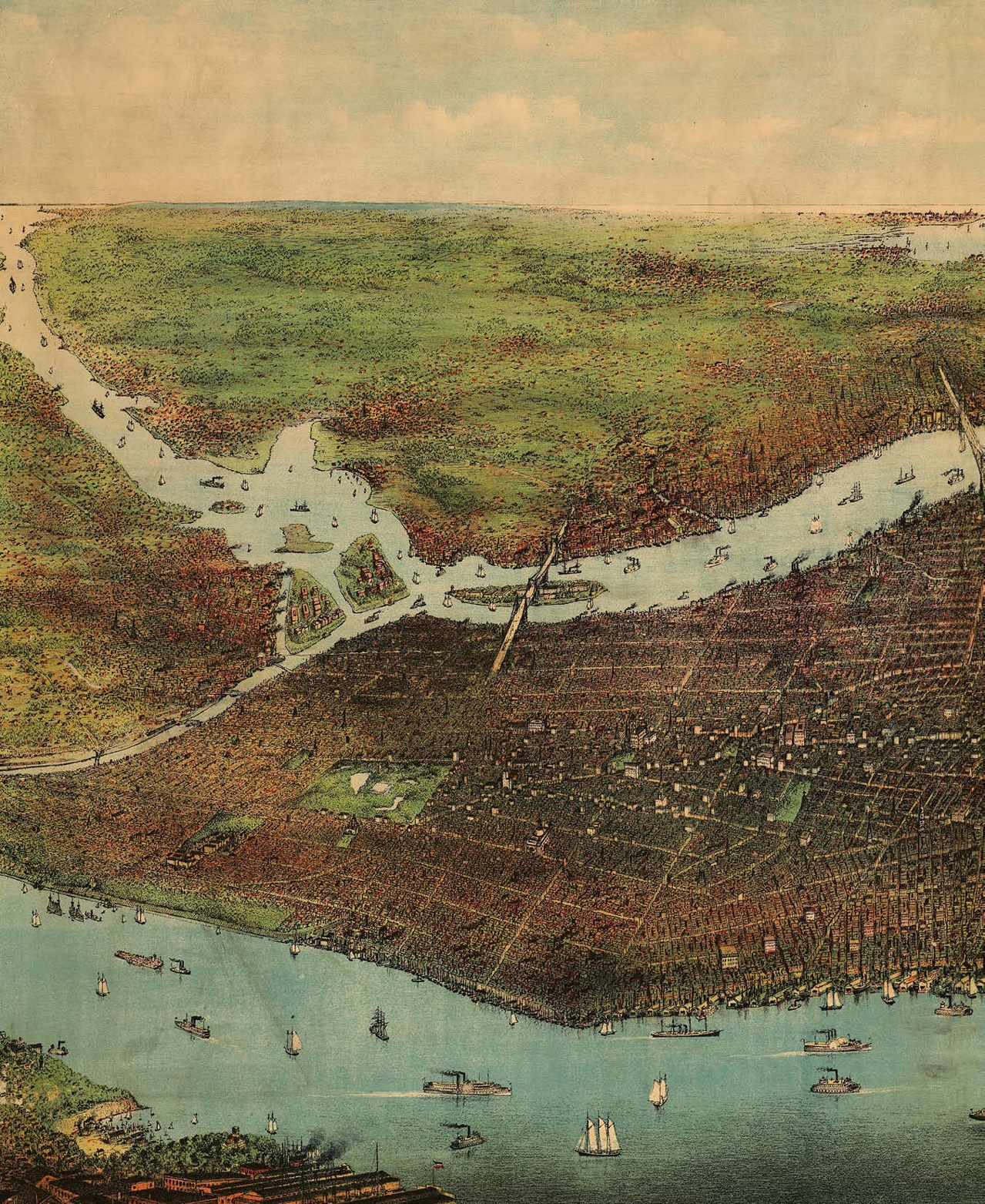

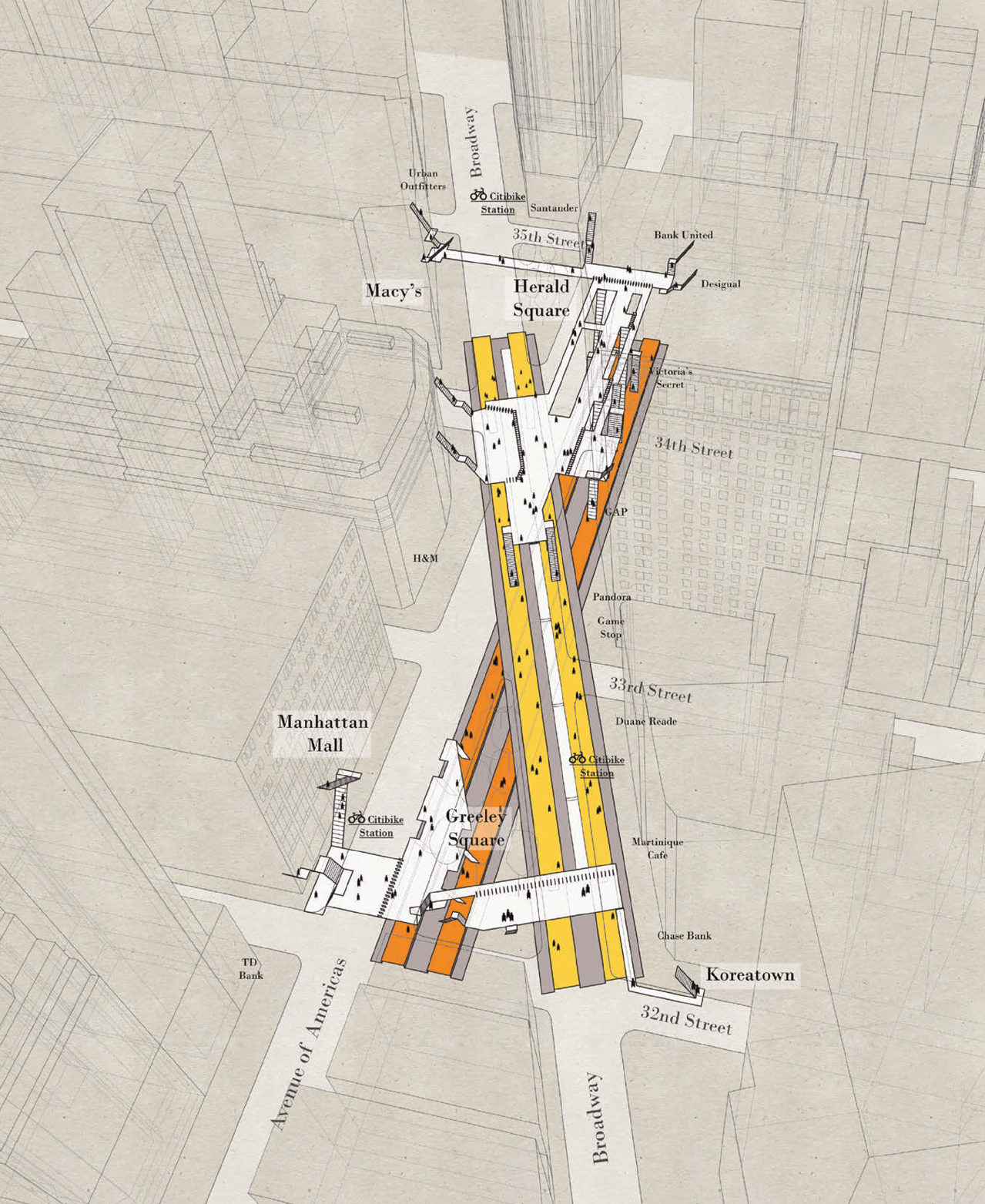

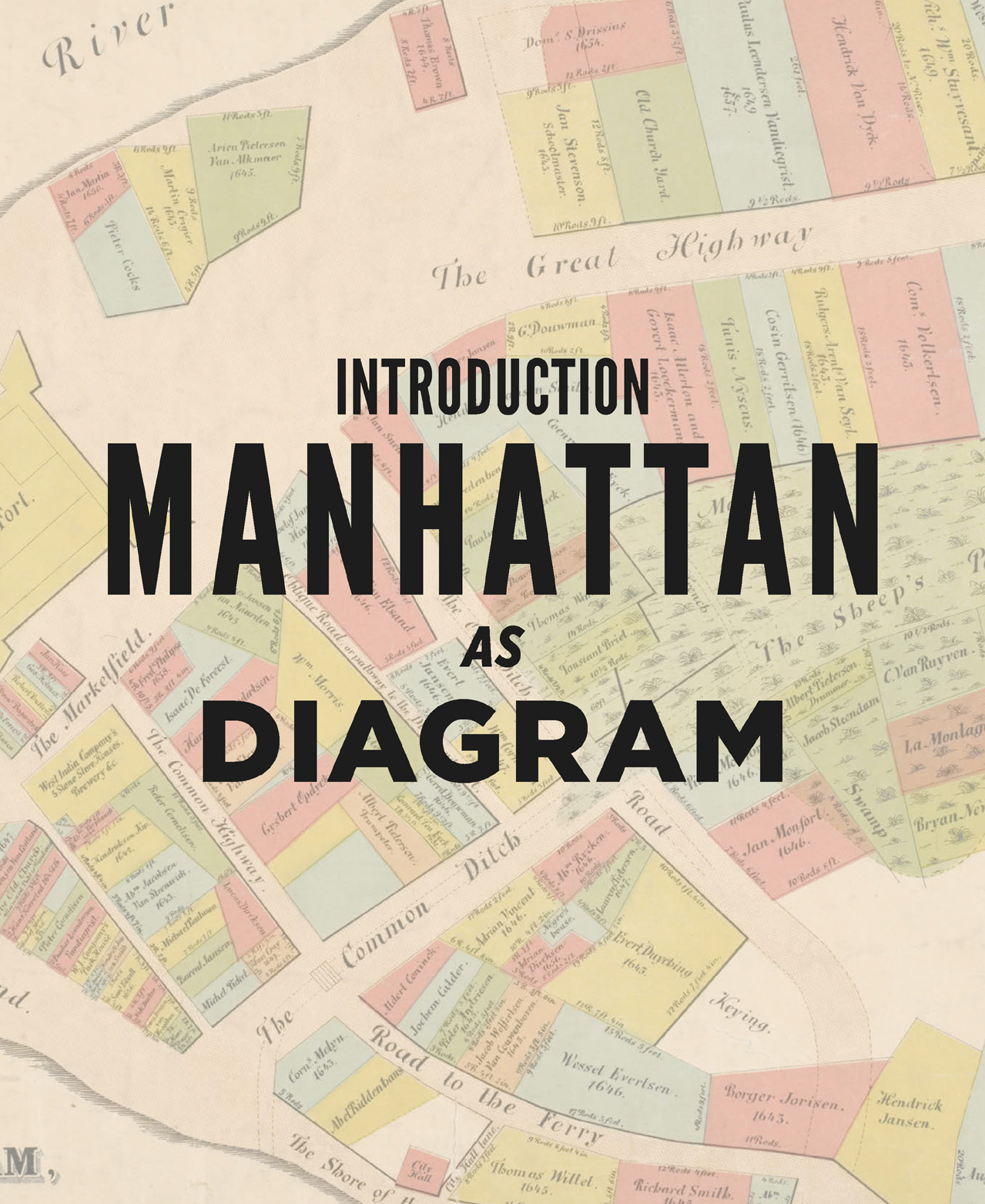

On maps and charts, Manhattan Island looks like an elongated chess

board with various anomalous protrusions. Its matrix of orthogonal

blocks, with a scattering of triangles, is largely filled in with rectangular

building lots. This is the diagrammatic foundation that, just as it helps the

wayfinder, shapes and shadows the charts, maps, graphics, cutaways, cross

sections, and other comparative and contemplative graphic depictions of

the city and its people, places, and things that you will find throughout

this book. Here, diagrams are keys to the city, providing fascinating, and

often surprising, insights into the inner and outer workings of Manhattan

from diverse perspectives, often with condensed and intense detail to sat-

isfy the most obsessive viewer. They show what is under the skin, behind

the curtain, below ground, or floating in air.

No word brings together these eclectic images more cohesively and

poetically than diagram . Diagrams have existed since the beginning of art

making. In recent yearsand notably with the advent of the computer

the genre has blossomed into a huge profession with its own specific

conventions and aesthetics, practicing what is known in the current

vernacular of design as data visualization and information graphics (and

at times information architecture), inventing friendly and accessible ways

to help us consume and digest our overabundance of data. In the end,

however, the new data viz is just more diagrams. In this book, the best

of the old and new sits side by side.

Diagrams explain the world, illuminating differences and similarities

among all sorts of things. The simplest chart can provide a visual clue to

help unravel the most convoluted phenomena, and yet, by virtue of visual

logic, the most intricate rendering may reduce complexity into digestible

forms. Further, we embrace diagrams not just to

understand how things work, but to also understand

how we work. These impersonal tools acquire indis-

pensable personal meaningsthey help us understand

the mechanics of our lives, illuminating experience

with criticism or humor. A Venn diagram will help us

define our place in the world, a flowchart can guide us

through a choice, a pie chart shows us how we spend

our time and moneythe applications of diagrams for

self-exploration are limitless and wondrous.

In the newspapers and magazines where many

of the diagrams in this book were originally published,

they were used to edify and entertain by combining

image and text within a single impactful graphic. As

Manhattans stories have been presented to the public

through graphics for decades, this diagrammatic

approach to journalism has shaped the global image

of the city.

In 1910, the New-York Tribune wished to impress

upon its readers the vast dimensions of the RMS

Titanic, then nearing completion in Belfast, Ireland,

and New York provided the perfect yardstick. Arthur

Ragland Momands illustration, Where Can We Dock

This Marine Monster When She Reaches the Port of

New York? (), is a cutaway view of the behe-

moth, comparing its bulk to existing and pass modes

of transportation, including a railroad train on her

upper deck and Henry Hudsons square-rigged Half

Moon resting crosswise, with her topmasts jutting

into one of the Titanic s dining rooms. The height

of the steamship is measured against a landmark

familiar to Tribune readers, the fourteen-story Postal

Telegraph Building on Broadway and Murray Street.

Even though it is now common to see huge oceangoing

apartment-house-sized vessels docked on Manhattans

Hudson River, this diagram, which alerted the public

that a new heavyweight contender was coming

to the worlds capital of bigness, has not lost any of

its impact.

In another eye-catching comparative diagram

celebrating bigness published in the Scientific Amer-

ican in 1906, illustrator C. McKnight-Smith showed

the Singer Building, then under construction and

the worlds tallest on completion, dwarfing a group

of world-famous monuments and looming over the

citys skyline (). As New York soared skyward,