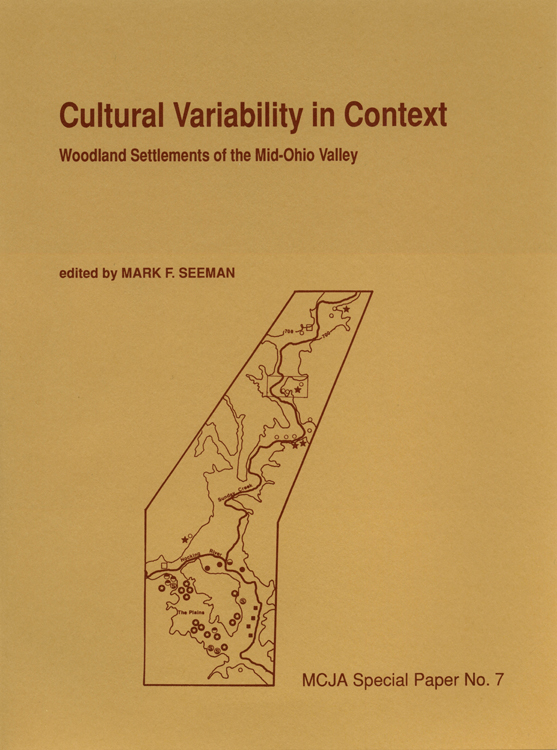

Cultural Variability in Context

WOODLAND SETTLEMENTS OF THE MID-OHIO VALLEY

edited by Mark F. Seeman

MCJA Special Paper No. 7

The Kent State University Press

Kent, Ohio, and London, England

MCJA Special Paper No. 7

1992 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Number 91-14831

ISBN 0-87338-452-0

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cultural variability in context : Woodland settlements of the mid-Ohio Valley / edited by Mark F. Seeman.

p. cm. (MCJA special paper ; no. 7)

Papers presented at the 54th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in April 1989 in Atlanta, Ga.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

ISBN 0-87338-452-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Woodland cultureOhio River ValleyCongresses. 2. Land settlement patterns, PrehistoricOhio River ValleyCongresses. 3. Ohio River ValleyAntiquitiesCongresses. I. Seeman, Mark F. II. Society for American Archaeology. Meeting (54th : 1989 : Atlanta, Ga.) III. Series: MCJA special paper ; 7.

| E99.W84C85 1992 |

| 977.01dc20 | 91-14831 |

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

This volume is a collection of symposium papers presented at the Fifty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in April 1989. The purpose of the volumeand the symposium from which it developedis to examine variability in settlement and subsistence in the mid-Ohio Valley during the Woodland period (ca. 1000 B.C.-A.D . 1000). Although such an examination has merits in its own right, the more important implications are for the development of broad models of cultural change, in this case, regarding the more specific question of developing complexity among tribal societies.

The mid-Ohio Valley provides the context for our investigations. From its origins in the hills of western New York to its confluence with the Mississippi River at Cairo, Illinois, the Ohio River system encompasses a tremendous expanse of territory and, predictably, a tremendous breadth of cultural diversity. For purposes of this volume, the mid-Ohio River valley, a smaller and more useful analytical unit, has been defined as extending from the mouth of the Muskingum River in the northeast to the Kentucky Bluegrass region in the southwest. The mid-Ohio Valley corresponds to no specific geographic or geomorphological unit, but rather, reflects a series of long-term cultural continuities recognized by previous investigators (e.g., Griffin 1983:293294; Webb and Baby 1957; see also Ray 1974:24). The notion of a mid-Ohio Valley region is comparable to Mayer-Oakess (1955) previous definition of an upper Ohio Valley region upstream, and Mullers (1986) recognition of a lower Ohio Valley region to the south below the Falls of the Ohio. The research reported in the present volume provides good spatial coverage across much of this mid-Ohio Valley area and permits a variety of comparisons.

The temporal period under consideration is the Woodland period, which in the Eastern Woodlands of North America extends from roughly 1000 B.C . to A.D . 1000 (see Griffin 1964:235245; Seeman 1986:564567; Snow 1980:261262). Although various authors have identified particular characteristics of the periodmound building, the general use of ceramic containers, long-distance trade, food production, an increased intensity of ceremonialism, and so forthmost of these relate to the more generalized process of increasing tribal complexity at this time. The available evidence makes it clear that mid-Ohio Valley societies played an important part in this larger process. A premise of the present volume is that in order to properly assess the place of the mid-Ohio Valley in affecting broader, interregional patterns of evolving complexity, it is important to document the nature of variability evident within the region. Most earlier summaries of mid-Ohio Valley prehistory present a normative view of cultural development; a proper emphasis on intraregional variability has not typified past work in this research area. A normative reconstruction can be useful, and from a practical standpoint, it is often the only viable approach when data are scarce. However, the limitations of this perspective are many, and they have been discussed at length in the literature (e.g., Ashmore and Sharer 1988:182192; Binford 1964; Butzer 1982:279294; Flannery 1976b).

Today in the mid-Ohio Valley there are many more archaeologistsand much more archaeological knowledgethan there was ten years ago. This is due almost entirely to the increase in CRM-related work done in the area. Most of the fieldwork upon which the present articles are based was publicly funded, much of it by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. One result is an emerging appreciation of cultural variability during the Woodland period. The usefulness of focusing on these patterns has been brought home by similarly targeted research in other areas, most especially in the central Mississippi and Illinois River valleys to the west.

In truth, much of the impetus for the present volume comes from recent work conducted in western Illinois. Here two large CRM projects, the FAI-270 project near St. Louis and the FAP-408 project near Pittsfield, Illinois, have provided an opportunity to examine variability among a variety of Woodland and Mississippian settlements (e.g., Bareis and Porter 1984; Farnsworth and Koski 1985; Morgan et al. 1986). Two patterns resulting from this work are of particular relevance to the present volume. First, phase-level, ethnic definitions need not necessarily correspond to neat geographic packages such as valleys or valley segments. Munson and Cook (1980) and Faulkner (1988:659) have made the same point for other areas, and Faulkners suggestion that some Woodland occupations in portions of central Tennessee may represent short-term forays from other areas is particularly relevant to the expanded spatial perspective provided by the present volume. Ethnographically, it is clear that few historic tribes or chiefdoms in eastern North America corresponded to the tight geographic limits of most Woodland or Mississippian phases used by regional archaeologists. Further, it should be noted that several of the western Illinois studies document the fact that there is considerable variability in the use of particular microenvironments over time. Munsons (1988) work in particular has emphasized that settlement decisions in primary and secondary drainages often are complexly bound together, and that at various junctures entire drainages may be underutilized or abandoned.

As the title suggests, the focus of the present volume is on variability in Woodland period settlement. The first article, by Maslowski and Seeman, is mainly concerned with providing an environmental setting within which the succeeding papers can be placed. It seeks to characterize both the general environmental context provided by the mid-Ohio Valley and to establish the range of environmental variability within different portions of the region. The following two articles by Niquette and Abrams are broad, drainage-based settlement studies of the Big Sandy and Hocking River valleys, respectively. They provide a good opportunity to examine comparatively the pace and direction of cultural development in different portions of the region.