First published 1992 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2011026249

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

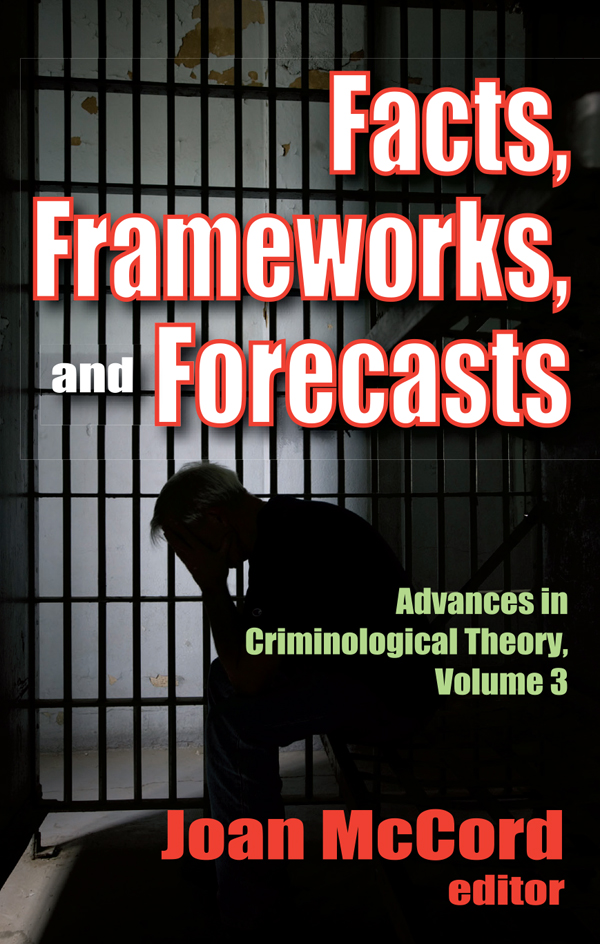

Facts, frameworks, and forecasts / Joan McCord, editor.

p. cm. (Advances in criminological theory ; v. 3)

ISBN 978-1-4128-4256-3

1. Criminology. 2. Criminal behavior. 3. Criminal behavior, Prediction of. 4. Crime forecasting. I. McCord, Joan.

HV6025.F23 2011

364.01dc23

2011026249

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-4256-3 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-88738-363-2 (hbk)

Contents

Joan McCord

Guenther Knoblich & Roy King

Daniel Glaser

Robert A. Rosellini & Robin L. Lashley

Robert J. Sampson

Ellen S. Cohn & Susan O. White

Joan McCord

L. Rowell Huesmann & Leonard D. Eron

Robert B. Cairns & Beverly D. Cairns

Behavior: Personality Theory Revisited

Judith S. Brook & Patricia Cohen

David P. Farrington

David Magnusson, Britt af Klinteberg, & Hkan Stattin

In a preface to the first volume of Advances in Criminological Theory, Marvin Wolfgang noted that criminological theory had stagnated. In that volume, I called for rethinking how theory should be developed. My hand was forced when Bill Laufer and Freda Adler put out the challenge: guest edit a volume. In accepting, my premise was that good theory begins with good data.

In the pages that follow, you will find an exciting smorgasbord of information. The volume begins with a chapter about biological conditions that have theoretical links with criminal behavior and ends with a chapter describing results of a study showing such links.

Early chapters discuss general issues related to crime. These are followed by expositions of theoretical orientations not typically found in criminological literature. The second half of the book describes seven longitudinal studies in four countries. Authors interpret their data to expose biological, social, and psychological factors they believe influence criminal behavior.

In the first chapter, Guenther Knoblich and Roy King discuss arousal systems, the gonadal axis, and serotonergic functioning. The presentation suggests several approaches to understanding how biological and social conditions may be linked to influence criminal behavior.

In the next chapter, Daniel Glaser takes an encompassing look at the variety in crimes. He sketches the contours of five ideal types before turning to consider crime prevention policies. In discussing primary, secondary, and tertiary crime prevention, Glaser integrates his broad experience of the criminal justice system with a review of theories about causes of crime.

Robert A. Rosellini and Robin Lashley describe Opponent-Process theory in terms that make sense of behaviors as diverse as opiate addiction and parachute jumping. They note differences in emphasis on attractive and aversive consequences as these shift through time and repetition. Their analyses suggest a developmental typology of criminal behavior.

Robert J. Sampson integrates community-level data with family differences and individual-level explanations of behavior. The integration includes developing the concept of social capital and linking it to differences in crime rates among communities. Sampson reminds us that families are affected by their communities even as individuals are affected by their families.

Susan O. White and Ellen S. Cohn describe an experimental study of legal socialization among college students. Their interpretation of the results leads them to focus on role-taking as a central means by which socialization occurs. They suggest that integration of beliefs and action is facilitated by taking the role of another.

After considering studies of altruism and aggression, I use data from the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study to test the relationship between criminal behavior and motives to injure and to help. The results lead me to focus on beliefs as playing a central role in criminal behavior.

L. Rowell Huesmann and Leonard D. Eron provide a guided tour through territory in which biological and environmental data interweave. They argue that cognitive processes formed early in life account for the high degree of continuity in aggression discovered in so many studies. Their chapter describes an information processing theory in which scripts are learned, rehearsed, and retrieved in response to variations in cues.

In describing their study, Robert B. Cairns and Beverly D. Cairns illustrate methodological issues of longitudinal research. The article links results of animal studies with those of aggressive and non-aggressive boys and girls from two cohorts. The developmental approach that infuses this research provides information about changing peer relationships and comparisons between self-evaluations and those by others.

Richard E. Tremblay gives historical perspective to personality theories before turning to his own longitudinal study tracing children through elementary school. Using descriptions of children in kindergarten to check the predictive value of a three-dimensional personality theory, Tremblay discovers important differences in patterns of antisocial behavior coinciding with earlier personality configurations.

Judith S. Brook and Patricia Cohen discover similarities and differences in the routes to drug abuse and delinquency among children studied over a ten-year period. They examine family context, parental and sibling antisocial behavior, child rearing, school environment, and peer influences and then use net regression techniques to specify which of the differences are statistically reliable. Their work addresses the issues related to whether various manifestations of deviance should be considered in terms of a single underlying tendency.

Working with data collected in Great Britain over the last twenty-four years, David P. Farrington emphasizes continuities through time and across traditional classifications of behavior. He contrasts short-term with long-term influences and develops a model to differentiate among people and to explain changes in their rates of offending.

The final chapter, by David Magnussen, Britt af Klinteberg, and Hkan Stattin, shows the power of combining a biological and psychosocial perspective on development. The authors discover developmentally significant differences appearing at age thirteen that distinguished between transient and persistent criminals. The data lend themselves to proposing two types of adolescents who commit crimes: those whose criminal activities are driven primarily by environmental conditions and those whose criminal activities are more closely linked to biological dispositions (which, they note, may be created by socialization practices or a result of interactions between biological and social events).