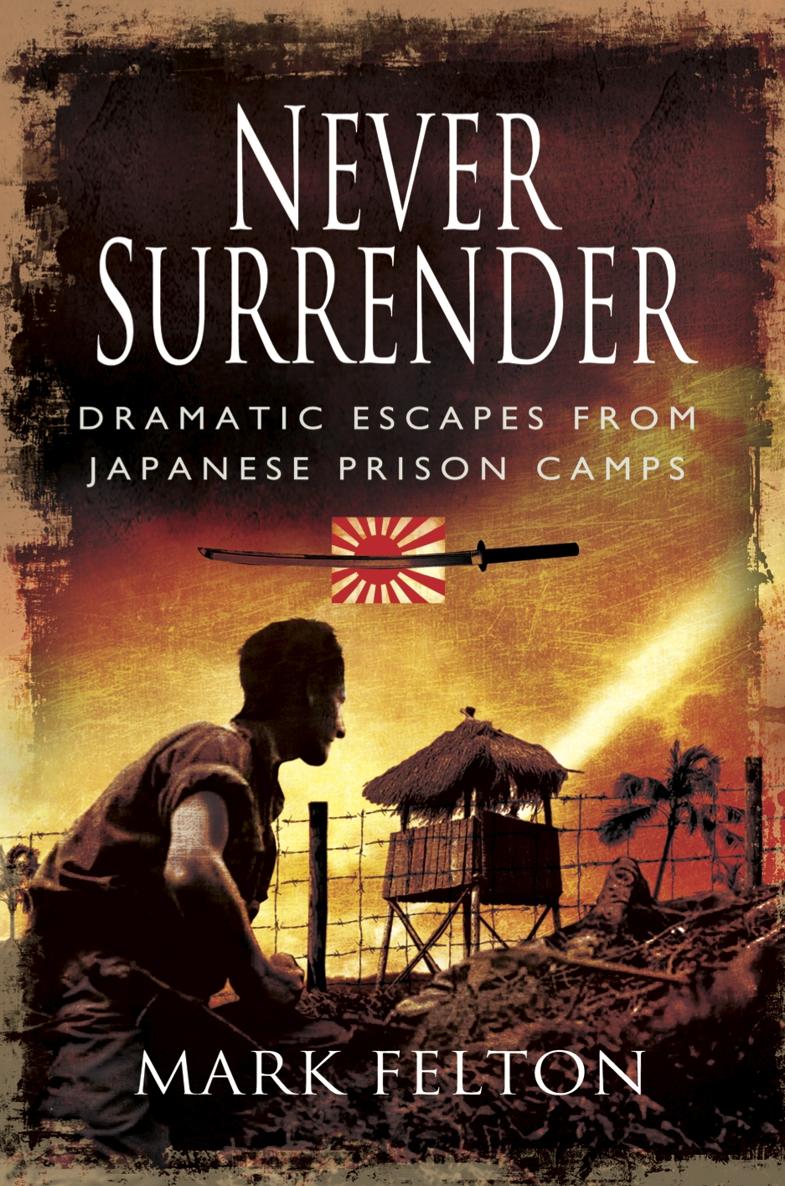

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Mark Felton, 2013

9781783830107

The right of Mark Felton to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Palatino by

Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire

Printed and bound in England by

MPG Printgroup

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen &

Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History,

Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

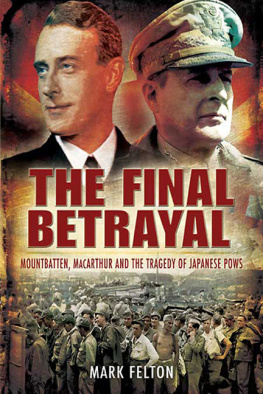

Introduction

17-year-old Private Bill Young escaped from the Japanese by accident, and although he was caught, his life was probably saved as a result. On 19 February 1943 Young had been slaving away for the Japanese as part of working parties that were constructing an airfield at Sandakan in northeast Borneo. Along with his comrade, 28-year-old Miles Pierce, Young had nicked off during the lunch break to the local village to try and obtain some more food. When the two men returned fifteen minutes later they discovered the airfield in an uproar. It came as a bit of a shock, on getting back to the airfield, to see the Nips jumping up and down, and waving their hands about. The air was alive with activity as two hundred gangs of fifty men each stretched on down the mile long, white granite-like strip... the guards were busy counting, and recounting their charges. Ichy, ne, san, si, go, roco, the cadence came loud and clear, recalled Young. Clear enough for us to realise that we were in the cacky poo.

Both men had already experienced punishment at Sandakan over minor infractions of camp rules and they had no intention of giving themselves up for a severe beating or worse now that they had been discovered missing from their work party. They could have been accused of attempting to escape and killed. It was either return to the fold, or be bold, and stay out in the cold; so escape seemed to be the safest way out, said Young. I always carried a little bit of a map that showed quite clearly that there was only a couple of inches to go across Borneo, right turn, and then, 6 inches past the coffee stain, and wed be home free in Australia; a piece of cake? A piece of half baked cake. Both men did not get far before they were recaptured. We were dragged over beside the boiler and beaten so badly that, as it was reported to the War Crimes Commission, wed both died... The Japanese mercilessly beat and abused Young and Pierce before shipping them off to Kuching to stand trial. They were found guilty of attempting to escape and sent to serve out their sentences at Outram Road Jail in Singapore. If they had not accidentally escaped in 1943 Young and Pierce would have perished along with nearly all of the other prisoners on the Sandakan Death Marches in 1945. Such was the fickle nature of life and death under the Japanese.

During the Second World War the Germans and Italians took prisoner 151,041 British, Australian, Canadian and New Zealand servicemen, as well as 24,400 Indian soldiers. Countless films, television programmes and books have highlighted the brave escape attempts that many of these prisoners made. Stories like The Wooden Horse, Colditz and The Great Escape have all entered the popular imagination. Escape appears in these works to be not only the duty of every able-bodied POW, but also a sport. Colditz Castle was packed full of Allied officers who had made repeated attempts to escape they were a hard core of plucky and determined men seemingly unbowed by capture. Several hundred Allied POWs successfully escaped from captivity in Germany, Poland and elsewhere and made it to freedom and a chance to fight another day.

In the Far East, the Japanese captured 73,554 British, Australian, Canadian and New Zealand servicemen and women, as well as around 55,000 Indians. Of this number only a tiny handful managed to escape and get home again. Escape is not a word usually associated with Japanese POW camps; instead we read and watch stories about death, suffering and survival, The Railway Man being the latest film to deal with those themes.

The reasons why so few Allied prisoners successfully escaped from the clutches of the Japanese are relatively straightforward, and they make those escapes that did succeed all the more remarkable. The first barrier for the Far Eastern POWs was distance. If an Allied POW successfully escaped from a camp in Germany he had several options. He could try to get to Switzerland, Spain or Sweden, all neutral nations where he could be spirited to Britain. By ship, England was but a few hours sailing time from Occupied Europe. In the Far East the nearest Allied territory was Free China, Australia or India, and most of the Japanese camps were concentrated in Thailand, Malaya, Indonesia, the Philippines, Eastern China, Korea or Japan. They were normally hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of miles from Allied lines. The geography was also fearsome as compared to Europe trackless jungles, massive mountain ranges, dry plains and huge shark-infested oceans.

The second barrier was the assistance the escapee could expect to receive in Asia. A healthy resistance network operated in France, Belgium and the Netherlands, not to mention in Occupied Scandinavia, all able to assist with a POWs safe passage. As well as local resistance groups and escape lines, the British had in place their own agents from MI9 dedicated to helping prisoners escape from German clutches in Europe. In the Far East, the story was quite different. In many parts of Asia guerrilla groups operated, many of them Communist. Some groups worked for the Allies, some worked for Japanese puppet regimes, and some worked for either side or for themselves. MI9, Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the American OSS all attempted to create networks that could reach into the prison camps, but (with some exceptions) it was chaotic at best and made doubly difficult by the Japanese refusal to report the locations of POW camps to the Red Cross, leaving many hundreds undiscovered until the end of the war.