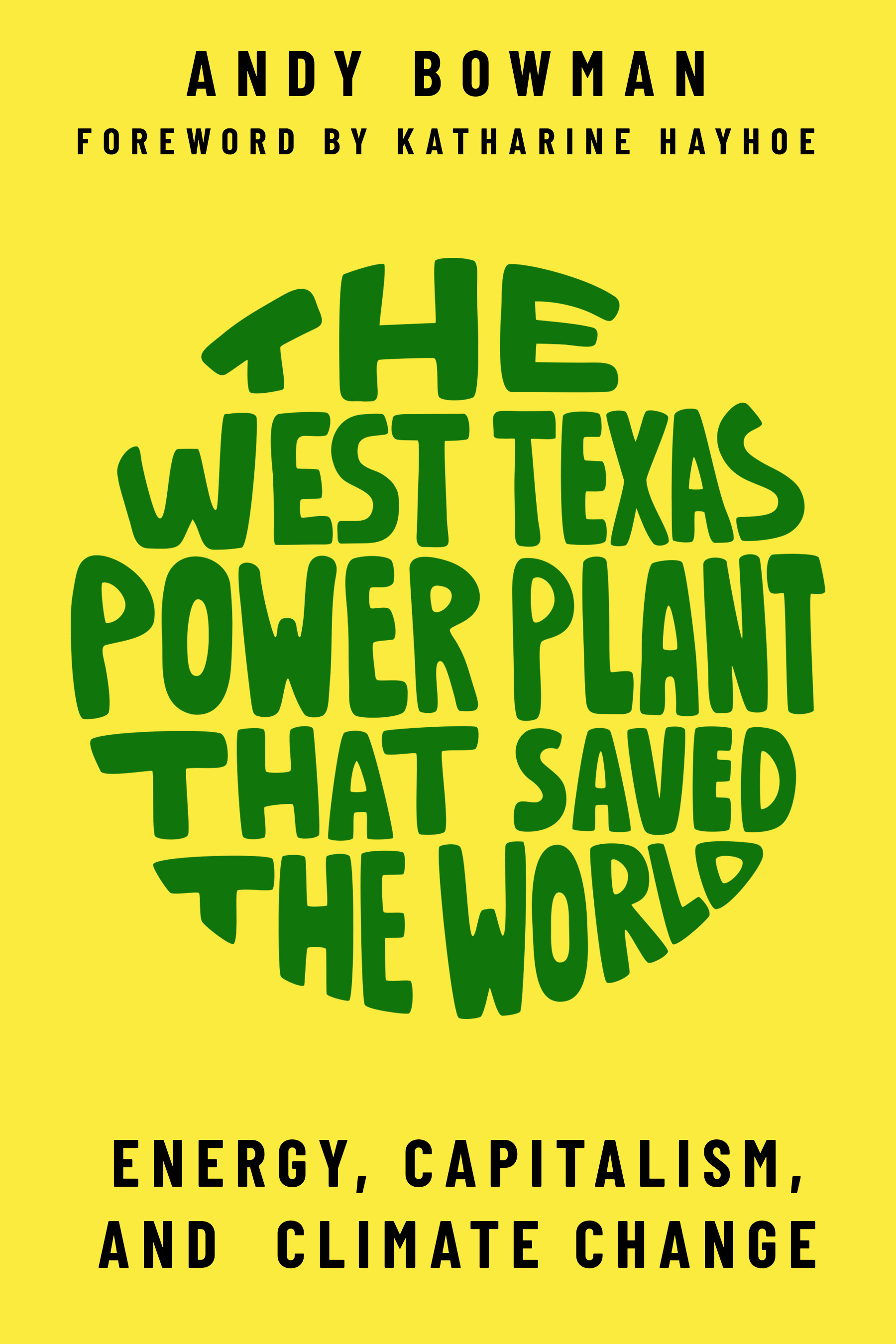

The

West Texas

Power Plant

That Saved

the World

Energy, Capitalism,

and Climate Change

Andy Bowman

Texas Tech University Press

Copyright 2021 by Texas Tech University Press

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including electronic storage and retrieval systems, except by explicit prior written permission of the publisher. Brief passages excerpted for review and critical purposes are excepted.

This book is typeset in EB Garamond. The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39. 48-1992 (R1997).

Designed by Hannah Gaskamp

Cover illustration by Hannah Gaskamp

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021937282

ISBN 978-1 - 68283-093 -2 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1 - 68283-094 -9 (ebook)

Printed in the United States of America

21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 / 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Texas Tech University Press

Box 41037

Lubbock, Texas 79409-1037 USA

800.832.4042

ttup@ttu.edu

www.ttupress.org

For my mother Phyllis and my grandfather Paul

Contents

Ours is the century in which all mans ancient dreamsand not a few of his nightmaresappear to be coming true.

arthur c. clarke, report on planet three and other

speculations , 1972

Foreword

C limate change is normal, natural, and necessary, a Houston man lectured me on Twitter. Another shared a homemade graph purporting to contain ice core data from Greenland that buttressed his argument that the planet isnt warming.

As a climate scientist, I find my inbox and social media feeds are regularly inundated with objections to the science I study. Do these objections have any basis in reality? The answer is, sadly, no.

Burning coal, gas, and oil provides us with energy. We use it to electrify our homes and our cities, power our cars and our planes, and fuel our industry and our manufacturing. For the last two hundred years, the vast majority of our energy has come from fossil fuels. However, their extraction and combustion produce massive amounts of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases. As these gases build up in the atmosphere, they are essentially wrapping an extra blanket around the planet, causing it to warm.

These facts have been well understood for a very long time. Scientists connected fossil fuels to carbon dioxide, and carbon dioxide to global warming, in the 1850s. By 1965, scientists were sufficiently concerned about the risks of this rapid, human-caused warming to formally warn a US president. And by 2020, after decades of research and thousands of scientific studies, scientists confirmed they were 99.9999 percent confident that humans were responsible for all the observed warming. It doesnt get any more certain than that.

Given how old and how solid the science is, when we hear people question it, we often assume they dont know the facts. And if thats the case, then the answer is clear: we need more and better education to get them on board. Anyone who understands the science, we think, will take this problem seriously and act quickly.

Does this approach work? In low-income countries with few fossil fuel resources and minimal heat-trapping gas emissions, more education does make people more concerned. And it should! But in rich countries like the US, blessed with plentiful coal, oil, and gas resources, we have contributed far beyond our fair share of heat-trapping gas emissions. We know this instinctively, even when we try to deny this knowledge or ignore it. So its no surprise that more information on how serious climate change is can be polarizing. For those already worried, it can make us even more anxiouseven panicked. But if we had already decided we werent concerned, then our defenses tend to engage even more strongly. Rather than changing our minds, often this just motivates us to seek out science-y sounding objectionslike the examples from social media I shared aboveto justify our position more ardently.

The reality is that such objections are simply a smokescreen that obscures the real reasons we balk at accepting the reality of a changing climate and our own contributions to this warming. These reasons are known as psychological distance and solution aversion . In plain English, we dont think climate change matters to us, and we dont think theres anything we can do to fix it.

Psychological distance is a phenomenon to which we humans are curiously prone. We have an inborn tendency to perceive many risks as being far away from us: in time, in space, and in relevance. We pile up debt on our credit cards, ignore recommended nutrition guidelines in favor of unhealthy foods, and tell ourselves well exercise tomorrow. Why? Its not out of any doubt that debt is real, heart disease can kill, and exercise is beneficial. Its because we dont see the risks as imminent. Climate change demonstrably invokes these avoidance mechanisms. Across the US, 72 percent of people agree that climate is changing, but only 43 percent believe it will harm them personally. Because we view this as a distant issue, it is all too easy to push climate change to the back burner. The more scientific warnings we ignore, the more numb we become.

Andy Bowman lives in Texas. Thats where I live, too. We know our state is naturally prone to more extreme, damaging climate and weather disasters than any other state. Weve lived through many of these events ourselves, and theyve left their mark on our memories: from the hurricane with which Andy begins his story to the massive dust storm that rolls over our town as I write.

Since 1980, Texas has been hit by 129 disasters whose damages topped $1 billion each. And thats exactly why Texas is also the most vulnerable state to climate impacts. Global warming is loading Texass already weighted weather dice against us. It is making our heavy downpours more frequent, our droughts longer and more intense, our heat waves more deadly, and our hurricanes much stronger and more damaging. Its estimated, for example, that human-caused warming of the planet was directly responsible for nearly 40 percent of Hurricane Harveys record-breaking rainfall and three quarters of the more than $100 billion in economic damages the storm caused.

Even more concerning, however, is solution aversionthe belief that the cure is worse than the disease, so to speak. In February 2021, we experienced this in real time. A massive winter storma vortex of cold air from the Arcticcovered the entire state in ice, snow, and record-breaking cold temperatures. It left millions of people without electricity, heat, or water, for days and even weeks, following the disaster. Our states response was a classic example of both psychological distance and solution aversion. To start with, these freezes have happened before: just ten years ago, as a matter of fact. After that freeze, reports and recommendations were made, yet none were implemented. Why not? The risks were viewed as distant. Who knew when the roll of the dice would bring back such a rare, unusual event, legislators reasoned. Then, as power outages spread across the state, solution aversion kicked in as well. Rather than acknowledge the fact that the earlier recommendations hadnt been heeded, Governor Greg Abbott went on television to blame frozen wind turbines. But when all the numbers were crunched, it turned out that a full 87 percent of the power outages were due to failures to winterize natural gas plants, with a small contribution from outages at nuclear plants. Wind accounted for only 13 percent of the outages. And even there, it was because Texas producers had declined to install the winterization technology that keeps them turning in much colder temperatures. Turbines from Antarctica to the Arctic have this technology and dont freeze up.