4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2021

Copyright Ece Temelkuran 2021, 2022

Ece Temelkuran asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

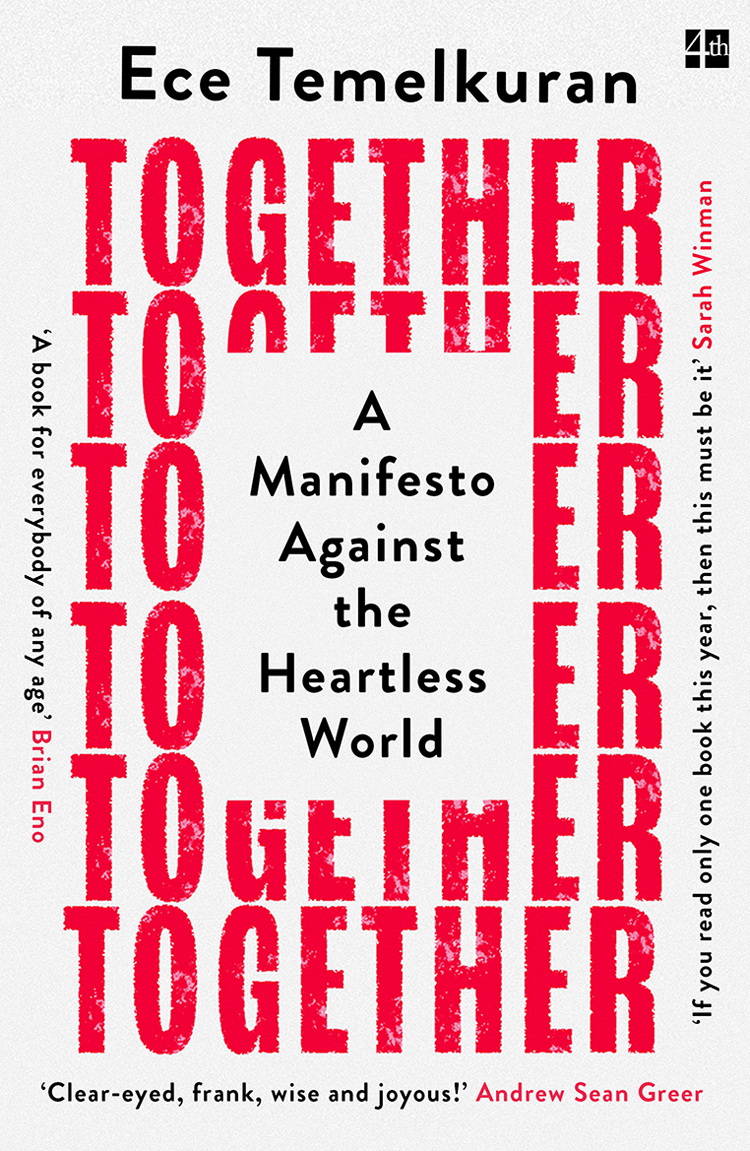

Cover design by Ola Galewicz

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008393847

Ebook Edition May 2021 ISBN: 9780008393823

Version: 2022-03-08

To little Valentino

I dare to promise you.

A talisman for now

Since we cant cry it off, we laugh: two determined headless chickens clucking into the apocalypse. The world is coming to an end, and for the last ten minutes, we have been meticulously trying to separate the plastic lining of our envelopes from the paper.

It is another early morning in the late spring of 2020, only a few weeks into lockdown, one week after a massive earthquake rocked Zagreb. And now, there is a dust cloud hanging over the whole city. We are two women of the same age standing on Marticeva Street, by the recycling bins, holding our half-torn bubble-wrap envelopes and shaking from our guffaws together even though we dont know each other.

But for just a split second, our eyes meet and we see each other and ourselves: our hair messed up, Covid masks crooked, and we are sorting our garbage into the appropriate bins to give us even a tiny bit of control over our garbage-like times since our latex-gloved hands are banned from fixing anything else. Pyramids and revolutions, symphonies and space travel, quantum physics and the Mona Lisa and here we are, at the start of the twenty-first century, looking like the garbage of human history.

Our sickening laughter is there to choke the all too human question of our times: Is this all we can be now? All we can do?

What do we do now?

During 2019, I was expected to answer that question after almost every talk I delivered, in countless different theatres in countless different countries. After How to Lose a Country was published, I spent almost the whole year speaking about the logic of the political machine that had created all the confusion, fear and desperation we found ourselves suffering. No country is immune to the paralysing political and moral plague of our times, I was saying. But by the time I managed to convince the relaxed Western audiences that this new type of fascism was waging a global war against basic human reasoning, my predictions were already coming true. Each time I finished a talk, for a brief moment, the same heavy silence filled the room right before the Q&A began. In that lead-like stillness, I eventually understood, many were trying to make a crucial choice: Shall I ask for the way out of this invasive insanity or shall I just go out and have a drink to forget? After all, many of us thought that the choices we had so far been provided with by todays world were rarely more meaningful than tearing bubble wrap out of paper envelopes. Or they were terrifyingly massive, like all-out revolution. The vast space in between where real life happened was rarely the issue. And in that real life a period of history was coming to end, but it rather felt like humankind was collapsing altogether.

All status quos have the magical ability of deceiving the masses into believing that when the system collapses everything else will collapse with it.

All systems act this way, like fearful ancient sailors: they warn that once you sail into uncharted waters, you will fall off the edge of the world. This is what were told is happening to us now. The economic and political system that we have built has reached its limits and, while it begins to fall, it threatens to drag us down with it. Any choice we make seems as ineffective as a bucket bailing water from a filling hull. The enormity of the chaos deceives us into believing that whatever we do is too small. And finally we tend to forget that our kind is in fact able to reinvent itself through even the smallest of things.

It is not clear from where I stand whether it is a childs instinct to be gentle with small objects or the learned disgust that keeps her from grabbing them fully. But Zeyno, a five-year-old, is collecting things on a deserted shore of the Greek island Kalymnos in the summer of 2019. She holds them up with the tip of her fingers and runs back to the parasol. But once each item is safely stored she resumes her slow walk, scanning the ground.

As her endeavour becomes so clearly persistent, two middle-aged women begin following her from opposite sides of the beach. Their lazy gait carefully conceals genuine curiosity as they pretend Zeynos parasol just happens to be on their way. They stop to glance at the mysterious pile. Pieces of plastic, one of them says. Ah, shes collecting garbage, responds the other. They exchange that mournful smile adults give when met with a display of enthusiasm. Zeyno, like a mother squirrel that has detected danger, runs back to protect the nest. Trying to catch her breath, she delivers a determined speech about how plastic is very, very bad for mother earth and how garbage can be turned into art, yes it can. After giving Zeyno an approving pat on the head, the women walk back to their parasols. Almost at the same second, though, they stop, pick up a piece of litter from the sand and return to contribute to the little girls collection. Instead of getting back to sunbathing they too begin to scan the sand. An unexpected midday poetry sweeps them along and they remember: Even in todays garbage-like times it is our inherent disposition to create beauty that has sustained our kind each time a system ended up in the dustbin of history. And during each collapse, despite those who believed that this was the end of it all, this essence of our kind has been the reason to renew our faith in humanity.

When I was Zeynos age, I was still able to hear the mute language of things. There was a drawer in our home that acted as the final waiting room for small objects that were no longer of use. The decision on their destiny was constantly postponed: pens with annoying temperaments that might work one day, gift package ribbons waiting to be used in emergency present situations, the rusting keys of long-gone doors, partially dried-out lipsticks, a broken hand mirror with anthracite veins, peeling plastic combs and all the et cetera of our life that could no longer claim their own places in our home. They all lay there waiting for my mothers next jettisoning-our-life moment. But their moaning, the disturbing cry of the fallen that only I could hear, was unbearable to my ears.

One day, I started sticking all these poor things together, a rescue operation of sorts. Gradually they became strange talismans that hung in my room. As they were placed back in the world as parts of a whole they were able to speak again.