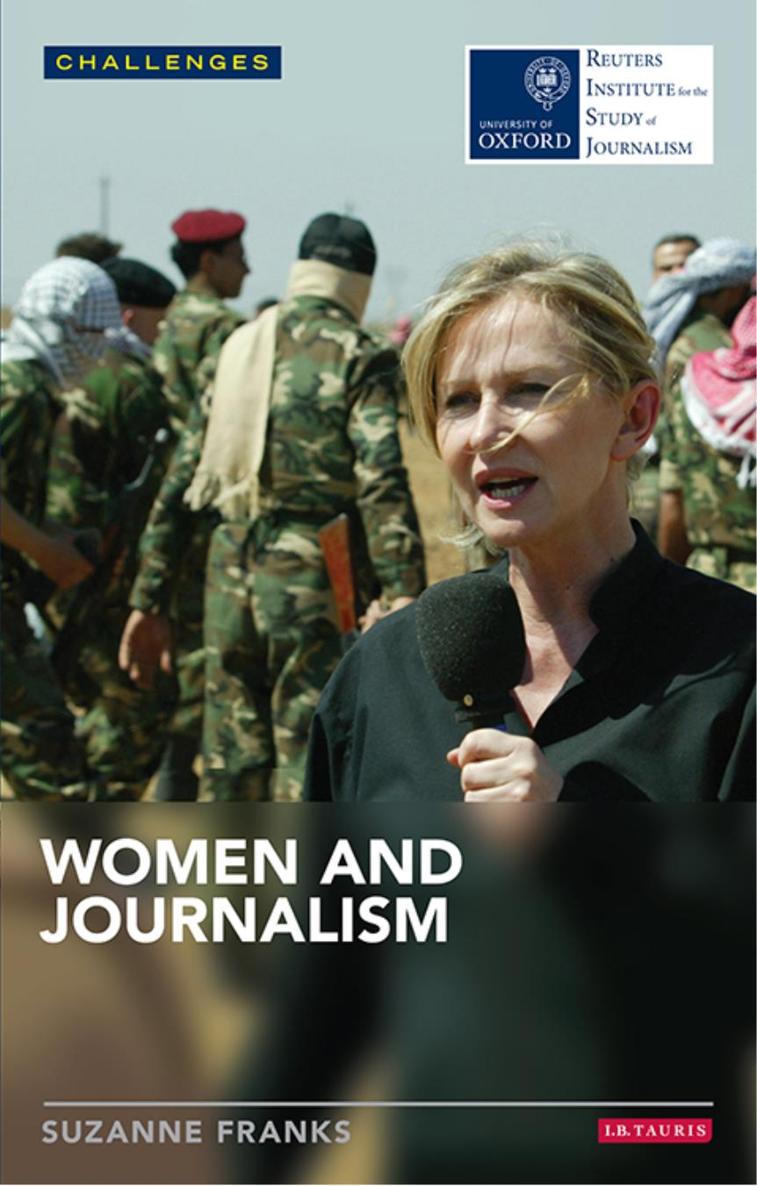

Suzanne Franks is Professor of Journalism at City University London. She was formerly Director of Research at the Centre for Journalism, University of Kent, and a news and current affairs producer for the BBC, working on Newsnight, the Money Programme and Panorama. Her publications include Reporting Disasters Famine, Aid, Politics and the Media and Having None of It: Women, Men and the Future of Work.

In many countries, the majority of high-profile journalists and editors remain male. Although there have been considerable changes in the prospects for women working in the media in the past few decades, women are still noticeably in the minority in the top journalistic roles, despite making up the majority of journalism students. In this book, Suzanne Franks looks at the key issues surrounding female journalists from on-screen sexism and ageism to the dangers facing female foreign correspondents reporting from war zones. She also analyses the way that the changing digital media have presented both challenges and opportunities for women working in journalism and considers this in an international perspective. In doing so, this book provides an overview of the ongoing imbalances faced by women in the media and looks at the key issues hindering gender equality in journalism.

RISJ CHALLENGES

CHALLENGES present findings, analysis and recommendations from Oxfords Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. The Institute is dedicated to the rigorous, international comparative study of journalism, in all its forms and on all continents. CHALLENGES muster evidence and research to take forward an important argument, beyond the mere expression of opinions. Each text is carefully reviewed by an editorial committee, drawing where necessary on the advice of leading experts in the relevant fields. CHALLENGES remain, however, the work of authors writing in their individual capacities, not a collective expression of views from the Institute.

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE

Timothy Garton Ash

Ian Hargreaves

David Levy

Geert Linnebank

John Lloyd

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

James Painter

Robert Picard

Jean Seaton

Katrin Voltmer

David Watson

The editorial advisers on this CHALLENGE were Steven Barnett and Robert G. Picard

Published in 2013 by I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright 2013 Suzanne Franks

The right of Suzanne Franks to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78076 585 3

eISBN: 978 0 85773 417 4

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Typeset by 4word Ltd, Bristol

Tables and Figures

Figures

UK newspaper by-lines, 2011 |

UK newspaper by-lines of front-page stories, AprilMay 2012 |

Executive Summary

Journalism is changing, as is the role of women in the workplace, but the two are not always evolving in harmony. Women are better educated and encouraged to achieve at work just as journalism intensifies, jobs become tougher, and the economic pressures become greater. The digital revolution means journalists can work from anywhere, but what is sometimes viewed as the electronic cottage may also become the electronic cage. As news cycles shorten and demands increase for a 24/7 multi-media presence, so the nature of the work has become more challenging. Meanwhile women still continue to shoulder a disproportionate burden in the home (either because society expects it or they want to) which makes things harder to manage if the workplace becomes more demanding.

Women substantially outnumber men in journalism training and enter the profession in (slightly) greater numbers, but still today relatively few are rising to senior jobs and the pay gap between male and female journalists remains a stubbornly wide one. The same is true across many Western countries. And older women, especially if they have taken a break, find it difficult to retain a place in journalism. The exception to this is in some former Eastern bloc countries where women continue to be well represented amongst the higher echelons of journalism and the media.

The fault line in most Western societies remains the same and this applies across many occupations. What now so often determines whether women are reaching senior posts is whether they have family responsibilities. These exacting roles such as news reporting or senior editor which are dependent upon a news or output agenda are difficult for anyone with other responsibilities. The relatively few women who do get these jobs at a higher level have few outside responsibilities; for example, they are far more likely than men to be childless.

Since the late 1980s the drive for female audiences to fulfil advertising targets benefited women journalists who were hired to provide a diet of softer, lifestyle, and feature journalism. And many of the women who did reach the highest levels came from this genre. This has prompted an ongoing debate about the feminisation of journalism.

There are still enduring stereotypes; women predominate on the lifestyle pages, but do not feature much in crime or sport. They are also far less likely to be seen on the front page, which leads to the tendency that Mens news is to write on the front page that a fire happened, womens news is to write inside why the guy lit a fire for the third time (Johnston, 2003). A critical mass of women in journalism at all levels is important in ensuring a greater multiplicity of voices. At the moment, there is a disproportionate lack of female sources, female experts, and even women considered as newsworthy subjects (except when they are victims or royal).

But the digital whirlwind has also created new opportunities and new forms of journalism and this is where women have flourished. They used to leave full-time journalism and write from home as freelancers. Now they can also keep abreast of the news agenda to edit remotely and indeed create whole brands through using social media. And these new ways of consuming media have also enabled women journalists to benefit. Where they can find new ways of doing things and when they carve a new niche, branding themselves in new forms through a blog or even as a war reporter this is where women have successfully reinvented themselves. When they enter existing structures they tend to be less successful. There is still evidence of a boys club and usually where there is a less transparent process, within a corporate hierarchy, then women lose out.

In the traditional structures of journalism there are many junior women but still no clear path of advancement the same issues recur that have been discussed for over a generation, ever since equal employment rights became a political reality. A number of exceptional individuals have achieved but this has not transformed the culture. There is a tendency to think that the argument has been won, but the concrete evidence shows a stubborn resistance to change across many Western countries though in the public-service media and in the Nordic countries things are more equal. It may be that in some ways the circle of intense demands and a wish to be involved in family life cannot be squared. Nevertheless, especially because at least a fifth of women today will not have a family, these arguments urgently need to be restated and recast for a new generation and a new digital environment hence this challenge.