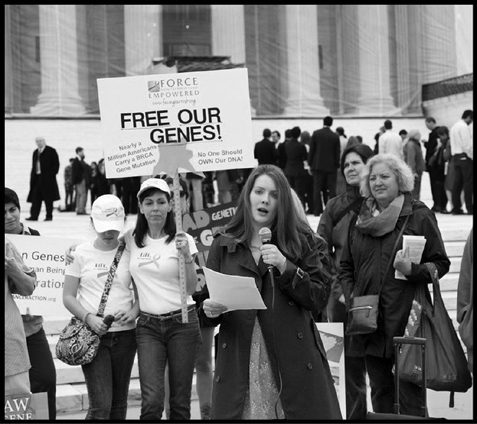

Rally outside the U.S. Supreme Court prior to oral arguments in AMP v. Myriad.

The Genome Defense

Inside The Epic Legal Battle To Determine Who Owns Your Dna

Jorge L. Contreras

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2021

For my mother, who gave me a microscope

and showed me its magic, and my father,

who let me launch rockets.

N early two centuries ago Thomas Jefferson and a trusted aide spread out a magnificent map The aide was Meriwether Lewis, and the map was the product of his courageous expedition to the Pacific. It was a map that forever expanded the frontiers of our continent and our imagination. Today the world is joining us to behold a map of even greater significance. We are here to celebrate the completion of the first survey of the entire human genome.

U.S. P resident B ill C linton (2000)

[I] f anything is literally a common birthright of human beings, it is the human genome. It would thus seem that if anything should be avoided in the genomic political economy, it is a war of patents and commerce over the operational elements of that birthright.

D aniel J. K evles and L eroy H ood , T he C ode of C odes (1992)

Contents

Preface

F ree our genes ! The chants began just after dawn on April 15, 2013, reverberating defiantly across the empty Supreme Court plaza. As the gray morning advanced, demonstratorsmostly women wearing ribbons and hoodiesposed for television crews and shouted into megaphones. They brandished signs and placards hand-printed with messages like O utlaw H uman G ene P atents and H uman G enes B elong to H uman B eings .

The case being argued that morning concerned a technical questionthe proper interpretation of Section 101 of the U.S. Patent Act. The legal briefs were laden with references to nineteenth-century precedents and details of molecular biology. Typically, cases like this attracted the attention of a few biotech lobbyists, science journalists, and curious law students. Yet on that day, the scene outside the court resembled a major civil rights demonstration. What was going on?

I n 2013, the United States Supreme Court was presented with a seemingly simple question: are human genes patentable? Its answer would have profound implications for the law, for science, for business, and for humankind in general. What exactly does it mean?

For the most part, the question is whether a single person or, more to the point, a single company can legally own the right to replicate the DNA that exists inside every man, woman, and child on the planet. And why would a company want to own this right and spend millions of dollars litigating over it? Because reproducing DNA in the laboratory is often the key to diagnosing deadly genetic conditions, assessing vulnerability to disease, and developing new drugs. In the United States alone, this is a half-trillion dollar market.

I spent much of one day in May 2009, in a large, artificially lit conference room at the Bethesda, Maryland, headquarters of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH, established in 1887, is the nations biomedical research agency; it funds close to $40 billion in scientific research each year. Modern chemotherapy was invented there. Its researchers developed the vaccines for yellow fever and typhus and made significant contributions to those for COVID-19. And in the late 1990s NIH led the massive multinational effort to sequence the human genome.

I was there to attend a meeting of the National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research, the body that had overseen the Human Genome Project and now serves as the advisory group to NIHs Genome Institute. In 2000, the Human Genome Project announced the first draft map of the genome of the human species, followed three years later by its complete DNA sequence. Now, the Genome Institute was leading even more ambitious projects aimed at mapping the invisible microbiome of organisms inhabiting the human body, discovering the association between genetic mutations and a host of human diseases, and uncovering the genetic code of cancer.

I was the only practicing lawyer on the eighteen-member council; most of my colleagues were geneticists, data scientists, and clinicians from prestigious research institutions. I was there because I knew something about patents, specifically about patents covering human genes.

In the late 1990s, when I was a junior partner at a large Boston law firm, I advised a consortium of pharmaceutical companies that funded research alongside the Human Genome Project. The consortium released its results into the public domain, so that all could use them freely. Though I cant take credit for it, the SNP Consortium, as it was known, was phenomenally successful and became famous throughout the genomics research community. As a result I got to know many of the leaders of the Genome Institute, and was invited by its then-director, Francis Collins, to sit on its advisory council. There, I heard reports on the most cutting-edge genomics research being conducted around the country and got to help, in a small way, to chart the future of that research.

I clearly remember the council meeting in May 2009. Alan Guttmacher, the acting director of the Institute, had just delivered a report updating us on the many different projects under way. We were taking our morning coffee break, and I checked email on my Blackberry. An interesting news item caught my eye. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had just filed a lawsuit against a Utah-based biotech company called Myriad Genetics. The ACLU, in its first-ever patent suit, sought to invalidate several of Myriads patents covering two human genes known as BRCA1 and BRCA2.

The genes, and Myriads patents, were well known in the field. Myriad had used them to build a lucrative business testing women for genetic variants that pointed to a dramatically increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer. I had discussed these very patents with Dr. Collins before I joined the Institutes council and shared his general unease with the practice of patenting complete human genes. Suffice it to say that many in the scientific community regarded Myriads patents, and the business strategies that it used to exploit them, with discomfort. In the NIH conference room that morning, the buzz of conversation swelled as more council members viewed the news reports on their devices. The scientific director of the Institute, Eric Green, was standing. The ACLU sued Myriad, he muttered to no one in particular. Wow. Murmurs of agreement echoed around the room.

From that moment, I was hooked by the case, which was known officially as Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) v. Myriad Genetics. Gene patents had been around for more than twenty-five years and were an accepted, if controversial, part of the legal landscape; could this unorthodox attack really work? At the end of 2009, for unrelated reasons, I left my law firm to pursue a career in academia. I gave talks about the case and wrote articles about it in law journals. But as the legal battle between the ACLU and Myriad progressed through the court system, from a district court in New York to the circuit court of appeals in Washington, DC, and eventually to the Supreme Court of the United States (twice), I became convinced that more was at stake than an obscure doctrine of patent law. The case involved a broad array of personalities, from scientists and doctors to lawyers, patients, and advocacy groups. It also attracted the attention of people at the highest levels of the Obama administration, which intervened in the case in unprecedented ways. And it garnered more coverage from the popular media than any other patent case in recent memory, including a segment on