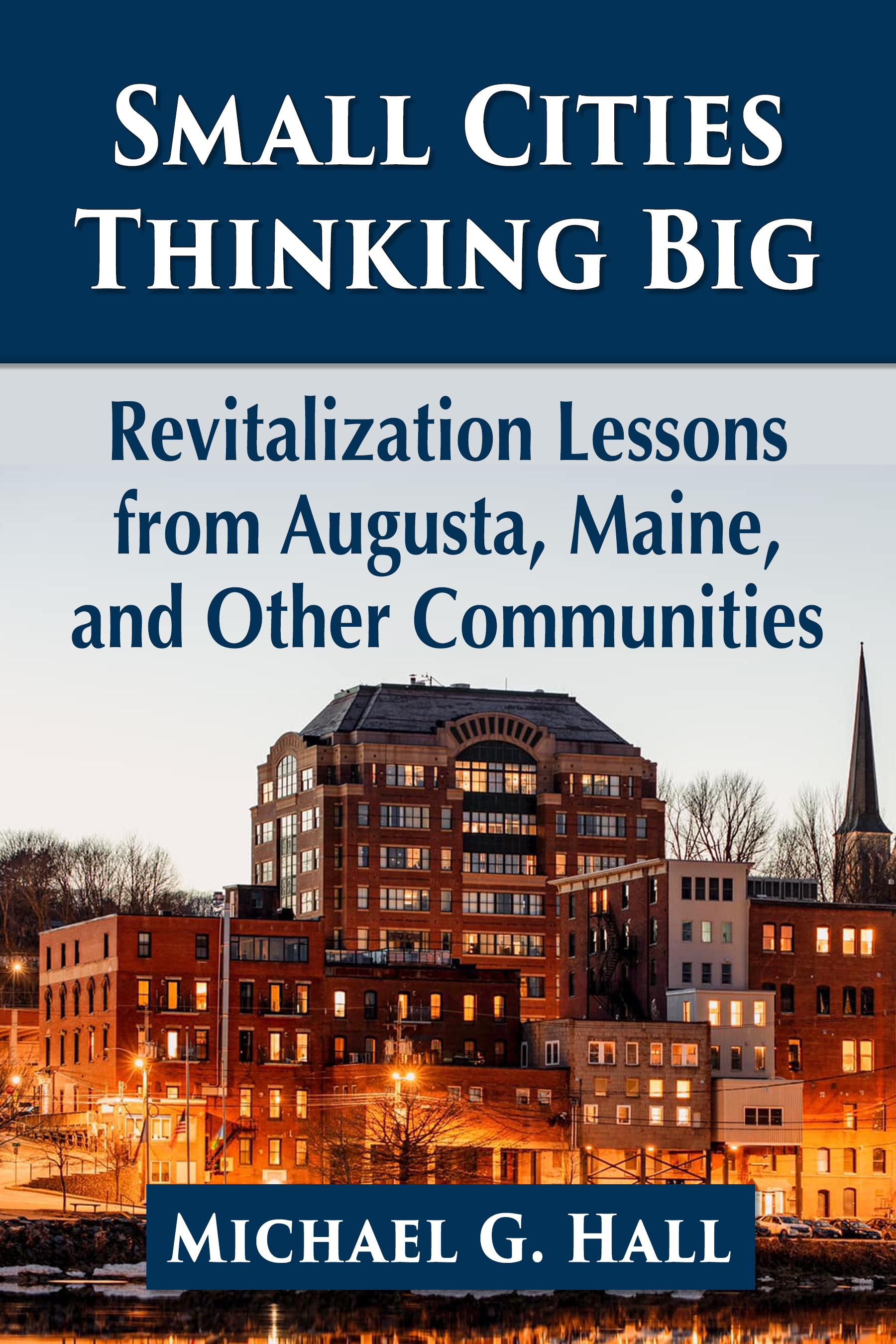

This book would not be possible without the participation of everyone involved. I personally want to thank and acknowledge Heather Pouliot, Shawn McLaughlin, Soo Parkhurst, Nancy Smith, Matt Pouliot, Larry Fleury, Cynthia Roodman, Tobias Parkhurst, Jesse Patkus, Andrew LeBlanc and Keith Luke for sharing their guidance and expertise. All are amazing individuals. and Im very lucky to count them among my friends.

In addition, I want to thank Dave Dostie for allowing me the use of his amazing photos.

Lastly, I want to acknowledge everyone indirectly involved for the strong moral support provided during the writing process. This book is larger than any I have previously written, and I sincerely appreciate the encouragement Ive received.

Introduction

On August 17, 2020, New York City was officially pronounced dead. Just four years shy of its 400th birthday, the City That Never Sleeps fell into a deep coma from which it has yet to awaken. The hollowed-out strip of Fifth AvenueManhattans go-to spot for all things luxurynow sits vacant, its windows boarded up. Times Square, once filled with throngs of tourists, is eerily quiet. The bright lights of Broadway are dimmed.

Longtime residents of the city are quick to remark that all this has happened before. Many still remember the heady days of the 1970s, when the city was on the verge of bankruptcy and denied a bailout. A 1975 article in the Daily News captured this sentiment perfectly with the headline: Ford to City: Drop Dead. Like the past, they proclaim that rumors of the citys demise have been greatly exaggerated. Still, to others, this time feels different. The sickness feels real.

What began as a panic over Covid-19 has turned into an expos of all things wrong with life in the Big Apple. Murders have skyrocketed, homelessness has spread, racial tensions have flared, and crime has reached decades-high levels. Shootings have surged 82 percent since May 2020 alone. and while some have since returned, others are continuing to stay away.

As moving trucks poured into the city, Governor Cuomo, desperate to stop the bleeding, begged them to come back:

I literally talk to people all day long who are now in their Hamptons house who also lived here, or in their Hudson Valley house or in their Connecticut weekend house, and I say, You gotta come back, when are you coming back? Cuomo said during a press conference.

Well go to dinner, Ill buy you a drink, come over Ill cook, Cuomo said, describing his pleas with wealthy New Yorkers.

As summer months led to clashes against police, as well as widespread looting and violence, these pleas have largely fallen on deaf ears. Covid-19 has shown them not only that they can live elsewhere, but also that they can live better.

No longer confined to an office, many have seen that work can be done more productively from the comfort of their living rooms. The lack of cultural options due to crowd restrictions has also forced them to reevaluate their locales as, without ready access to museums, Broadway plays or fine dining establishments, all they are paying for is overpriced real estate in cramped and crowded conditions.

As days pass, with some prognosticators indicating full recovery for the city is expected to take 10 years or longer, it has become clear that what the pandemic has done is more than just put a dent into the city: It has actually torn the Band-Aid off New York City exceptionalism.

For decades, this myth of exceptionalism has been propped up in the if I can make it here, I can make it anywhere trope. However, this trope was only perpetuated as long as people wanted to move there. Well, as 2020 dragged on to 2021, it appeared that people no longer desired to flock to New York. Its too dangerous. The health risks are too great. Its too expensive.

While it would be tempting to lay all of this at the feet of the pandemic, this is actually something that has been happening for quite a while. In fact, during the last three years, roughly 146 people a day have been fleeing the city. This, in itself, is troubling enough for a great city like New York, but as well see, these are trends that are being repeated in urban centers nationwide.

The Death of the Large American City

It might seem that the issues raised above are unique to New York; however, New York is just a harbinger for other major cities. As is the case for most trends, New York was simply the first urban center to experience these changes on a mass scale. As the epicenter of the pandemic, it was seen as a symbol of the kinds of flaws that overcrowding can bring, particularly if the structures that supported it, such as readily available access to public transportation and close access to city parks and other amenities, were abruptly halted. Take away these things, and the appeals of city life are less than noteworthy. As noted by Sue Hough (2020), the pandemic has demonstrated:

The rat race is not all it was cracked up to be.

Work doesnt need to happen in an office building.

Losing the daily commute is not a bad thing.

Focusing life around home reduces expenses.

Family-centric living has unexpected benefits.

Social distancing may become permanent.

While New York seems to be getting the brunt of attention regarding demographic decline, eleven of the largest American cities with populations over a million lost people last year as well. According to analysis by Jed Kolko of Indeed.com, the cities of Los Angeles and Chicago saw two of the largest percentage declines. Without immigration gains, seven more large metros, including Miami, Boston, Providence, San Diego, San Francisco, Milwaukee, and New Orleans, would have shrunk.

Throughout much of the 2000s and into the 2010s, Americas major cities, including New York, reversed prior decades of population loss as incomes grew and crime fell. Some neighborhoods even surpassed their historic peak populationsfor example, New Yorks Bronx borough, which lost some 20 percent of its residents in the 1970s alone. Newcomers rented out or bought up real estate in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis as urban job creation revved up. But over the past decade, housing creation failed to keep up with job creation: 3.9 new jobs were created in New York City for every one new housing permit.

Even mid-size cities have not been immune to this decline. Fully 48 major metro areas showed peak growth during the first six years of the decade and only oneTucson, Arizonarealized its highest decade growth in 2018 to 2019.