Praise for the first edition of The Dust Rose Like Smoke

An excellent scholarly introduction to the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century history of the Sioux and the Zulus as well as a thoughtful analysis of United States and British expansion.

Journal of American History

The first detailed, in-depth comparison of the closing of the American and South African frontiers.... Gump has performed a valuable service by showing that the events surrounding Little Big Horn and Isandhlwana were comparable incidents in a global narrative.

Journal of Social History

Informative to both specialist and general readers.

American Historical Review

[Gumps] opening chapters show a mastery of all the relevant historical literature. Indeed, they could be set for any undergraduate course in imperial history as textbook examples of how to build up a comparative framework of analysis.

Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History

Praise for the second edition of The Dust Rose Like Smoke

It would be difficult to exaggerate the value of this brief but pioneering book as a successful example of the historian using the comparative approach. Historians of the American West should find this model especially challenging and liberating. It is also a good example of how an ethnohistorical approach can explain the dynamics of the internal politics and subimperial politics of Zulu and Sioux leaders.

Ethnohistory

This unique and imaginatively written book will serve as a model and hopefully inspire others to consider comparative studies.

Canadian Review of American Studies

An excellent example of what comparative history can be. James Gump has managed an entertaining and thoughtful book, one that will illuminate the history of southern Africa and the United States for both academic and general readers by thoughtfully tying them together.

Montana: The Magazine of Western History

Both academics and general readers will be fascinated by the authors insights.... Gumps superb work will surely serve as a model for additional comparative studies.... [It is] an analytical book that admirably fulfills the highest expectations of comparative history.

Wyoming Annals

Engrossing.

Choice

Genuine comparative history is rare, and James Gump has provided an admirably clear and concise example of this important approach to historical analysis. All who are interested in Native American, South African, or imperial history will benefit from his account.

Robin Winks, Yale University

I find the comparison of the Sioux and the Zulu a fascinating excursion in historical parallels and contracts.

Robert M. Utley

A fascinating and intellectually stimulating work of interest to both specialists and non-specialists alike.

Journal of African History

The Dust Rose Like Smoke should delight students of the Sioux War. It is precise and well-paced, intertwining its two case studies to throw new light on an old subject. It will stimulate debate.

North Dakota History

Tightly organized and interestingly written. The data are current and well analyzed, and the comparative approach adds insight.... The book is informative to both specialist and general readers.

American Historical Review

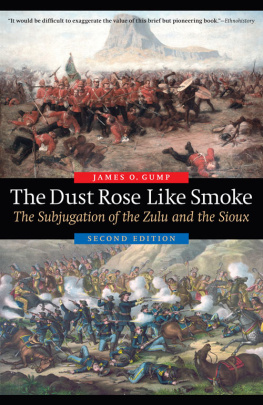

The Dust Rose Like Smoke

The Dust Rose Like Smoke

The Subjugation of the Zulu and the Sioux

Second Edition

James O. Gump

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln & London

2016 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

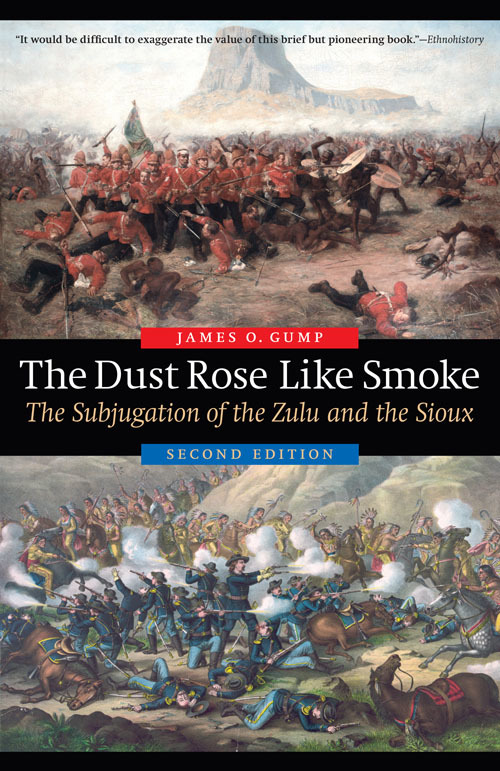

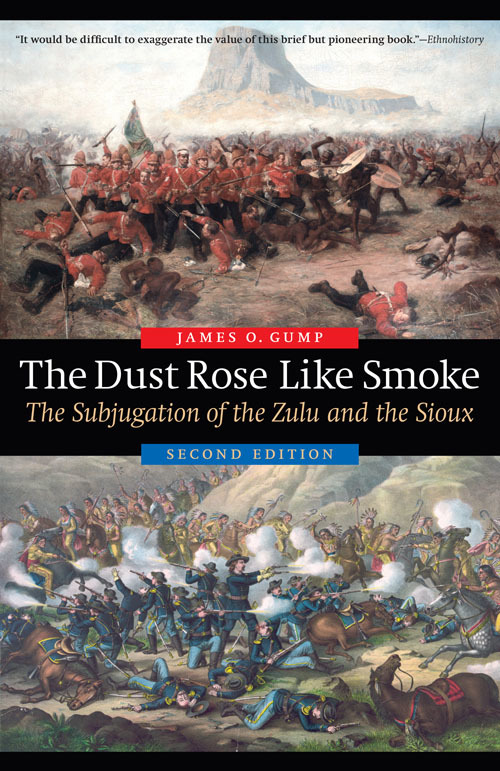

Cover images: (top) The Battle of Isandlwana: The Last Stand of the 24th Regiment of Foot (South Welsh Borderers) during the Zulu War, 22nd January 1879, c. 1885 (oil on canvas), Fripp, Charles Edwin (18541906) / National Army Museum, London / Bridgeman Images; (bottom) Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZC 4-511

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gump, James O. (James Oliver)

The dust rose like smoke: the subjugation of the Zulu and the Sioux / James O. Gump.Second edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-7863-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8453-1 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8454-8 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8455-5 (pdf)

1. Dakota IndiansHistoryCross-cultural studies. 2. Dakota IndiansWarsCross-cultural studies. 3. Dakota IndiansGovernment relationsCross-cultural studies. 4. Zulu (African people)HistoryCross-cultural studies. 5. Zulu (African people)WarsCross-cultural studies. 6. Zulu (African people)Government relationsCross-cultural studies. I. Title.

E 99. D 1 G 86 2016

323.1197'5243dc23

2015024757

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Lee Ann and Scott

Contents

In May 2001 I met with Leonard Little Finger in his office in Oglala, a small town on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in southwestern South Dakota. Little Finger, a lifelong resident on Pine Ridge, taught Lakota studies to Lakota children at Loneman School. Soon after we exchanged pleasantries, Leonard shared a story about John Little Finger, his grandfather. When I was a boy of eight or nine, Little Finger related, I went fishing one day with my grandfather John in the reservoir near Oglala. Soon after they began fishing, both heard the rumble of thunder in the distance. Grandfather said that the thunder reminded him of Wounded Knee. It was the first time he ever talked about Wounded Knee. Little Fingers grandfather then lifted his pants leg to reveal a hideous scar and proceeded to tell his grandson the story about that terrible day in December 1890.

On December 29, 1890, troops from the U.S. Seventh Cavalry, George Armstrong Custers old regiment, opened fire on a party of mostly unarmed ghost dancers on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, homeland of the Oglala Lakotas. When the firing ceased, several hundred Lakota people, including men, women, and children, lay dead at Wounded Knee. Some bodies were found three miles from the original Lakota encampment, gunned down in cold blood. On New Years Day 1891 a troop detachment returned to the killing ground at Wounded Knee. The soldiers dug a large pit, collected the frozen Lakota corpses scattered about, and tossed them into a mass grave. After the winter passed, the Lakotas put

Historians have often described Wounded Knee as a battle rather than a massacre,

One of the victims at Wounded Knee was Big Foot, John Little Fingers grandfather and Leonards great-great-grandfather. Big Foot, a Miniconjou Lakota chief, served as the leader of the ghost dancers camped at Wounded Knee Creek. Big Foot and his followers, approximately four hundred people, turned to the Ghost Dance religion in the late summer of 1890. The Ghost Dance emanated from the teachings of Wovoka, a Paiute living in Walker Valley, Nevada. During a solar eclipse on January 1, 1888, Wovoka experienced an apocalyptic vision of a new world that featured the return of Indian ancestors, plentiful buffalo herds, and the destruction of the white race. Wovokas teachings spread rapidly among the western tribes and were embraced enthusiastically by many Lakotas residing on their reservations in the Dakotas. The dancing, meant to hasten the new millennium, generated paranoia among some reservation officials, who conjectured that an Indian uprising was imminent. For example, the agent at Cheyenne River Reservation, Big Foots homeland, labeled the Miniconjou chief and his followers as hostiles in the fall of 1890. In fact, Big Foot was an old man in extremely poor health who wanted to avoid hostilities with the U.S. government. Two-thirds of his followers consisted of women and children.