Barajima Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

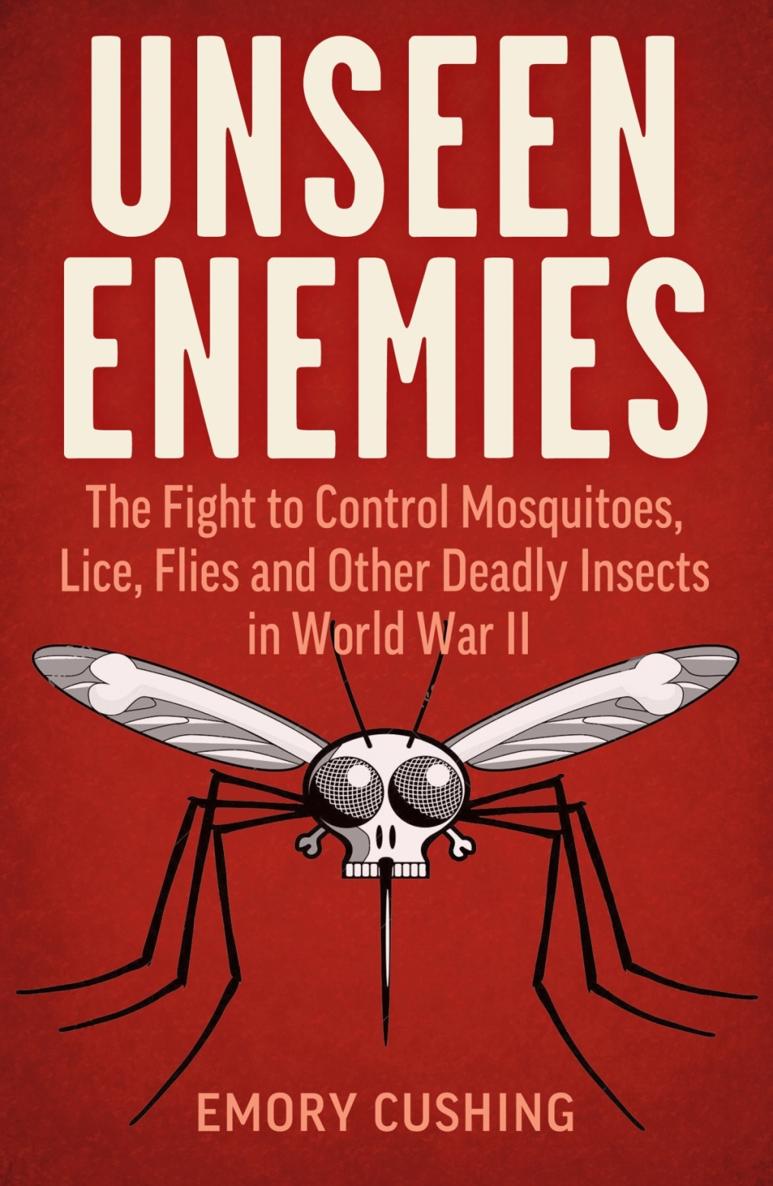

Unseen Enemies

The Fight to Control Mosquitoes, Lice, Flies and Other Deadly Insects in World War II

EMORY C. CUSHING

Colonel, U.S. Army, Retired

Unseen Enemies was originally published in 1957 as History of Entomology in World War II (Publication 4294) by the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Preface

History reiterates how insects and the diseases they carry have changed the course of wars. Typhus, malaria, dengue, plague, the dysenteries, and numerous other diseases transmitted by insects have played an important part in determining the destiny of nations. The role of insects in limiting production of foods, feed, and fiber is important in peacetime but often becomes an acute problem during periods of war.

World War II differed from previous wars. Far-seeing military surgeons, aware of the part insects play in the outcome of wars, made possible the planning of research programs in entomology. Agricultural leaders realized that agricultural production and its protection were essential to the winning of the war and that insect control was vital to any program of increased production. The successful conclusion of these programs assured ample food supplies and enabled the Allied forces to press forward to victory without the hitherto constant attrition of manpower caused by insect-borne diseases.

This was the first war in which entomologists had a favorable opportunity to demonstrate their ability to prevent annoyance and disease caused by insects. Their development of insecticides to control insects attacking man, animals, and agricultural crops was rated by leading scientists as second in importance only to the discovery of atomic fission. Other discoveries were less spectacular but were nonetheless important.

These entomological developments, originally for war purposes, have benefited the world. Hundreds of thousands of people have been saved from illnessor deathbecause of the research in entomology and the accomplishments of entomologists during World War II. Many crops show marked increases in yields which coincide with the extensive use of new pesticides developed during and immediately after the war.

These great advances were the result of co-ordinated efforts by many individuals. It is not possible in this history to credit individual entomological contributions to the war effort. It seems more appropriate to emphasize their team accomplishments in the fight for a Fifth Freedom, the Freedom from Many Age-old Insect-borne Scourges.

The manuscript of this History of Entomology in World War II was prepared under the general direction of a joint advisory committee appointed in 1947 by the presidents of the then Entomological Society of America and American Association of Economic Entomologists. Committee members were:

Representing the Association

Edward F. Knipling

Stanley W. Bromley (deceased)

Representing the Society

Paul W. Oman

Ralph W. Bunn

Individual sections were reviewed by members of the joint committee and David G. Hall, and supplemental information was added to several of them in order to amplify entomological contributions to the war effort. An entirely new chapter VII on the contributions of civilian entomologists to the war effort was written by a later addition to the joint committee, Ralph W. Sherman.

I am especially grateful to the members of the joint committee in the preparation of the manuscript for their many helpful suggestions and criticisms. I am indebted to my wife for much clerical assistance in arranging and typing the text material, and to Miss Sylvia Gottwerth, Historical Section, Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Army, for assistance in finding needed reference material. Finally, to the Entomological Society of America is due credit for making the preparation of this history possible, and to the Smithsonian Institution for arranging its publication.

EMORY C. CUSHING

I. Mans Early Association with Insects

Of the creatures that emerged from the ooze of a nebular universe, one was the primordial ancestor of insects, another the progenitor of man. The former set out quickly on its evolutionary trail and eventually produced some 2,000,000 species of insectsseveral millennia before the human race settled down to stake its chances of survival in the world on the single genus and species, Homo sapiens . From the very beginning, man and insect have been destined, with rare exceptions, to be mortal enemies wherever their trails crossed in their struggle for existence.

The earliest records of mans association with insects now lie buried under many centuries of antiquity. All evidence remaining indicates that mans forebears were plagued by insects. When Pithecanthropus descended from the arboreal recesses of his simian ancestors some 500,000 years ago, it seems quite likely that his insect enemies followed him. The Scythians and Peruvian Indians still search for a living morsel of protein and vitamin in the head hairs of their young, a practice still common among monkeys and other primates and probably inherited from some not too remote ancestor.

How many centuries did it take to learn the use of insects for food, poisons, and magic by present-day natives of Ovamboland, Africa? Fifteen thousand years ago an artist depicted on the walls of a Spanish cave the scene of his neighbor robbing a bee tree. Infestations of lice exist today on some of the oldest mummies. About 2500 B. C. a Sumerian doctor inscribed on a clay tablet a prescription for the use of sulfur in the treatment of itch. Modern dermatologists but recently abandoned that remedy.

Only four substances produced by insects have become of worldwide commercial importance to man: honey, silk, lac, and beeswax. After man became dependent upon certain agricultural commodities for food, the pollenization work of insects insured the fertility of his crops. The other side of the ledger, however, is greatly weighted by the misery caused man by his six-legged associates and their close relativesticks and mites.

Germs existed in the world long before either man or insects made their appearances. Pathogenic organisms affecting man violated a fundamental biological law somewhere along their evolutionary trail in that they failed to provide a means of insuring their survival. Certain of the insects took over this problem for some of them, usually with immunity from harmful effects by the pathogens. They became the disease carriers from infected hosts to new ones among both animals and plants. This alliance between insects and pathogenic parasites no doubt was in effect well in advance of mans debut on earth. Mans forebears and other animals were suffering from such insect-borne diseases not too long after our earliest ancestors emerged.