BENEATH THE SKIN

A BODY OF ESSAYS

The pieces in Beneath the Skin were originally commissioned, performed and broadcast as part of BBC Radio 3s ongoing series A Body of Essays, originated and produced by Kate Bland at Cast Iron Radio.

WELLCOME COLLECTION is a free museum and library that aims to challenge how we think and feel about health. Inspired by the medical objects and curiosities collected by Henry Wellcome, it connects science, medicine, life and art. Wellcome Collection exhibitions, events and books explore a diverse range of subjects, including consciousness, forensic medicine, emotions, sexology, identity and death.

Wellcome Collection is part of Wellcome, a global charitable foundation that exists to improve health for everyone by helping great ideas to thrive, funding over 14,000 researchers and projects in more than seventy countries.

wellcomecollection.org

BENEATH THE SKIN

Great writers on the body

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London

WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Published in association with Wellcome Collection

183 Euston Road

London NW1 2BE

www.wellcomecollection.org

Copyrights in the individual works retained by the contributors

Diality from I Knew the Bride by Hugo Williams Hugo

Williams and reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd.

The authors and publisher would like to make clear that some names have been changed in the text to protect privacy.

Typeset in Granjon by MacGuru Ltd

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78816 095 7

eISBN 978 1 78283 467 0

INTRODUCTION

THOMAS LYNCH

To have a body is to learn to grieve, wrote Michael Heffernan in his poem In Praise of It. This was the opening line of the penultimate poem in his first of now many collection of poems a book, like most slim volumes of verse, ignored on five continents, by an author who is internationally unknown, but who has, none the less, happened upon a truth, to wit: it is only in the body that our longings reside, our sorrows, our joys. If our hearts are broken, they are tucked beneath our sternums, snug in our pericardia, thumping out their iambic tunes. Mostly in the bones is where we ache for the embrace of another of our kind, or feel the residual of ancient wounds, old damages, wars long lost or won or fought to standstills. And only through the parts of bodies does mortality work its way into our demise the cancer or the cardiac arrest, infarction, aneurysm or embolus. We are an incarnate species, embodied, brought into being by the conduct of other bodies, their parts and aspects, attachments and penetrations, the workings of their mysterious components and consortiums.

Even words, we claim in faith, become the flesh.

And whilst we are men and women of parts, we are also, in our own flesh, singular enterprises, solo endeavours. Three cubic feet of bone and blood and meat, as Loudon Wainwright wrote for his son, Rufus, to sing into the new century, in his tune, One Man Guy.

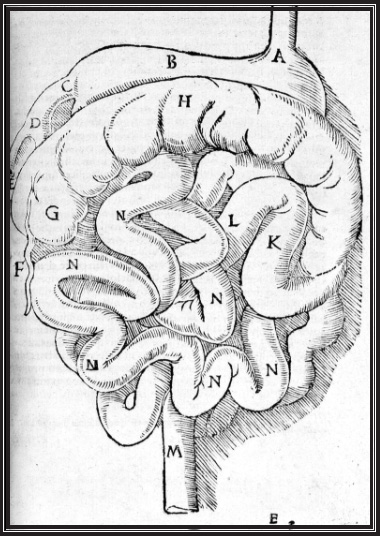

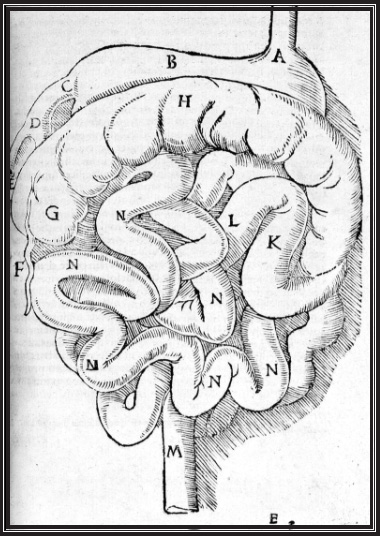

So the collection of essays assembled here goes some way towards making sense of the human condition by examining its particulars. What about the bowel or brainbox makes us who we are?

Was it the bad heart valve or the club foot, the cancerous bladder or the high cheekbones that shaped the rich internal course of our personal narrative? We can only guess. Our mothers eyes? Our fathers hairline? The freckles, the feet, the heart failure? Who can know how we came to be the ones we are?

We have gathered here a little catalogue of usual suspects, the shared systems of the greater and some lesser animals: guts and lungs, gall bladder and skin the innards and outer parts in hopes that by knowing the part we might better know the whole of our predicament and condition.

How is it that the parts engaged to send out a presidential tweet storm one day can enact Rachmaninoffs Second Piano Concerto the following evening? And while the heart becomes a ready metaphor for love and longing, grief and bereavement, the core of being, what case might we make for the symbolism of the pituitary gland? Or when guts are the locale of valour, the cerebellum where a soul might reside, to what end, we might wonder, that first segment of the small intestine, the duodenum? Could it be to further our interest in etymology? The medieval Latin whence its name comes duodeni, meaning in twelves refers to the fact that, where small intestines are concerned, size apparently matters: the breadth of twelve fingers approximates the length of the duodenum.

We are wholes and parts, one of a kind, and one of a kind. Still, here is where the part exposes something of substance about the whole, and why writers and readers, as much as medicos and anatomists, ought to be eager to understand these details of our bedevilments and being.

The father of modern essaying, Michel de Montaigne, in an effort to understand his kind, advised the test and measures method, believing, as he wrote in his masterful Of repentance, that Each man bears the entire form of mans estate. High in the library of his solitarium, he studied his body, its senses and sounds, gases and appetites, longings, desire. So, in that spirit, here are some bits and pieces, small gravities, an effort to better understand humanity by looking at the human being, the sapient animal that is Man by meditating on its parts.

INTESTINES

NAOMI ALDERMAN

The proximity of the anus to the genitals, Freud tells us, is the source of much if not all human neurosis. Its fashionable to distance oneself from Freud these days, to say I wouldnt go that far and of course Freud was sex-obsessed. But I would go that far, and most humans are sex-obsessed.

The gut, frankly, is a problem. What it does is not only mysterious and puzzling as are all our internal organs to a great extent but also difficult for us to bear. And when we start to think about the symbolism of the gut, we might understand what Freud meant.

At one end of the gut is the mouth a delightful place of many different kinds of joy. And then, at the other end, theres the anus. It produces farts, which stink of decay, foulness and poison. It makes poo, also foul-smelling, bearing disease, a sticky, stinky, brown contaminant. And it comes out of us! And not just out of our own bodies, but out of a hole right next to the parts of the body that can give us such great pleasure, whose development indicates adulthood, which can produce new life. Its like a terrible joke played by human biology, to drag us down from the heights to the depths, to remind us that whatever ecstasy we find, were also, essentially and at all times, full of shit. This is why poo is so funny. This is why we have to laugh at it. If we didnt laugh, wed cry.

Next page