First published in Great Britain

2016 by Aurum Press Ltd

7477 White Lion Street

Islington

London N1 9PF

Copyright Max McKeown 2016

Max McKeown has asserted his moral right to be identified as the Author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Aurum Press Ltd.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material quoted in this book. If application is made in writing to the publisher, any omissions will be included in future editions.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Digital edition: 978-1-78131-634-4

Softcover edition: 978-1-78131-518-7

2016 2018 2020 2019 2017

For my children, Bront, Zak, Steiny, and Reuben.

Each one beautiful, talented, and not finished yet.

CONTENTS

- PART ONE:

NURTURING YOUR NOWNESS - PART TWO:

THE THREE STREAMS OF #NOW - PART THREE:

THE #NOWIST TOOLKIT

Guide

INTRODUCTION

LETS START WITH #NOW

A ll weve got is #Now. Life, composed of a billion moments, from our first to our last thoughts. Some voices tell us to slow down, yet our human nature urges us all to move forward.

Some people resist this evolutionary momentum. They listen to the voice that tells them to slow down and develop habits to keep them from going anywhere new or better. They may push back against the natural flux of sensations labelling them interruptions or irritations and so waste the spontaneous energy of life lived effortlessly.

This book argues that for most people, most of the time, it is better to lean towards action rather than inaction. Nowists act on their belief that they will be happier and healthier if they keep moving. That they will achieve more and experience more if they move forward than if they stand still. The virtue of impatience is often of greater practical use than the vice of self-denying, motion-delaying, joy-draining, now-numbing patience.

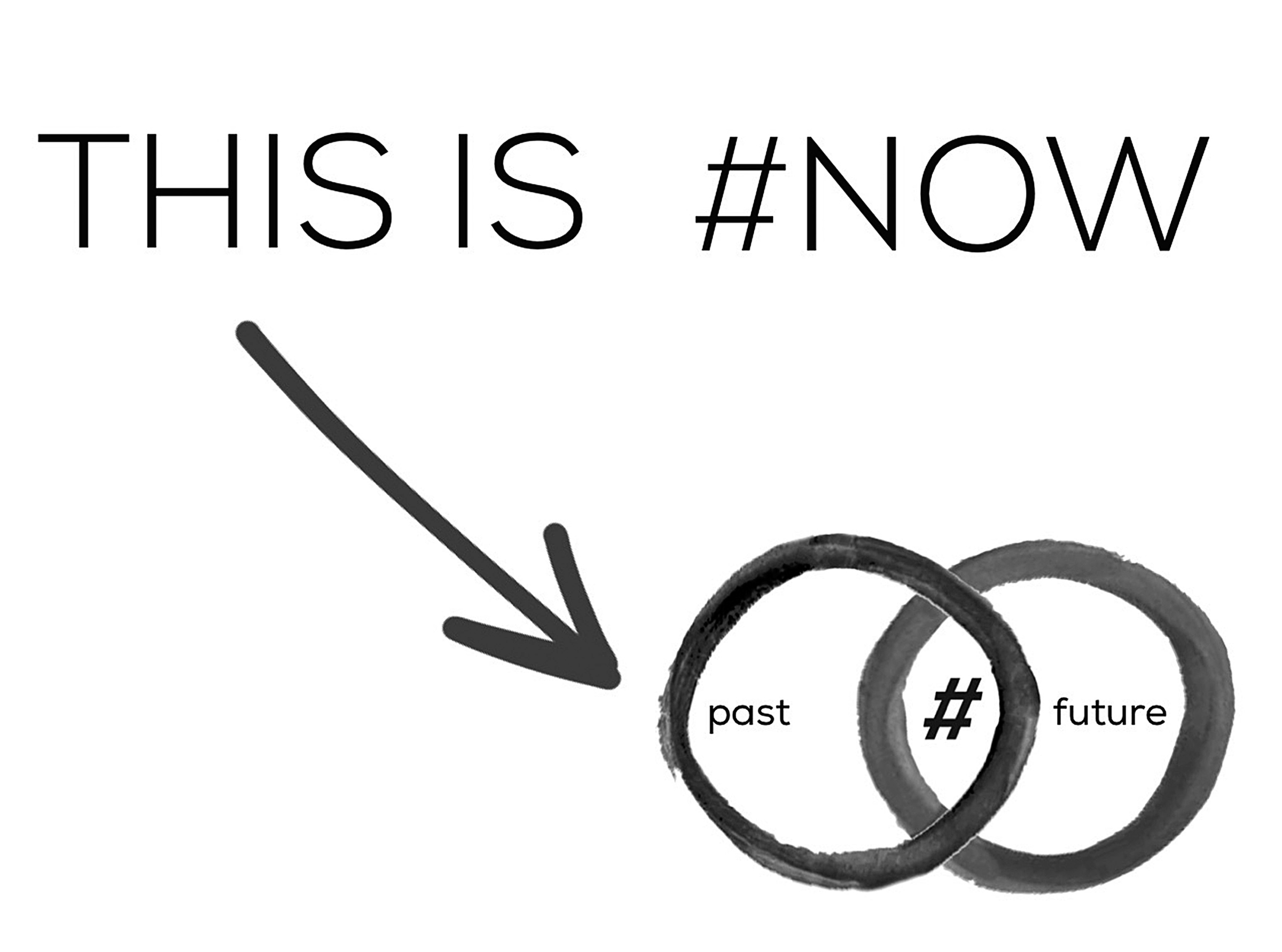

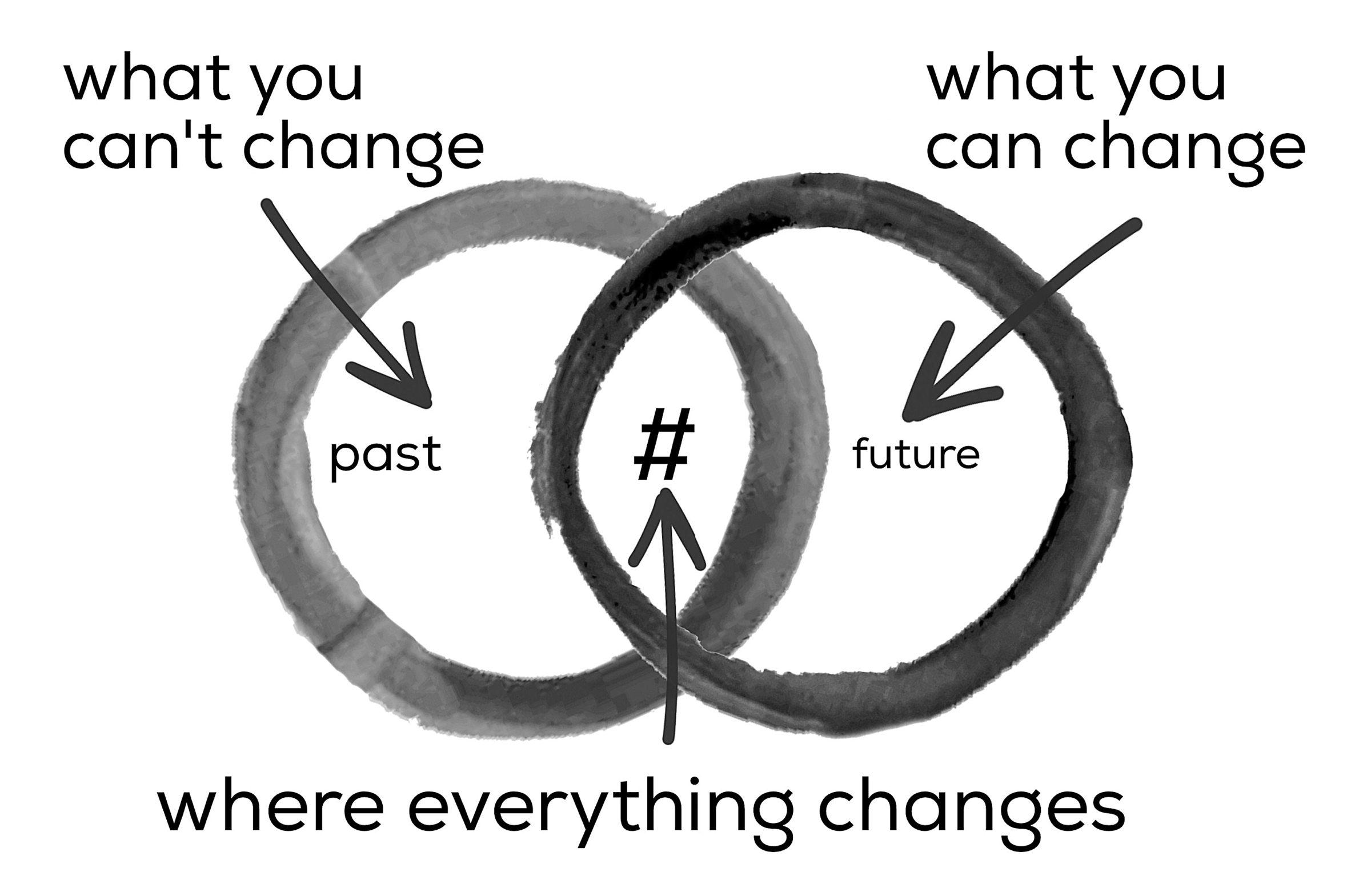

The circles on the cover and on the previous pages represent time and our perception of time, with the present at the intersection of past and future. The # represents Now. It is the point at which life is experienced and action can be taken or not taken. It is here that everything you do is done. And it is when everything you will ever make happen first happens.

Your #Now can be happy and connected. Or unhappy, disconnected and overwhelmed. Your #Now can be bored or captivated, scared or fearless, joyful or joyless. Nowists get off on getting on, so they run when they could walk, jump when they could sit, and dance when they could sit at the edge. They regret inaction, so simply act.

This is a book about the joy of moving. It is a book about motivation, because motivation means to be moved. This is also a book about what it takes to keep moving ways of making the effortless decisions required to clear a path for clear effortless action and the benefits this brings for your sense of power and well-being.

It explores surprising discoveries that reveal powerful truths about how we use our individual #Now. How easily we can slip into a passive Thenist state where our time is spent comparing ourselves with others, regretting what could have been, complaining about what is, and fearing what might never happen. If were too careful, we can end up with a thousand different action plans that block taking any action, and leave us worrying rather than loving life.

To accurately describe the alternative, a Nowist approach, were going to learn more about functional impulsivity, and the locomotion mindset. And then were going to reveal more threads, including the ability to see patterns at speed, the ability to use mental time travel effectively, and the ability to take mental shortcuts to action. Taken together were going to discuss the kind of behaviours that effectively harness the power and joy of #Now.

PART ONE

NURTURING YOUR NOWNESS

CHAPTER 1

YOUR NEED FOR SPEED

I n the last couple of decades of the twentieth century, with the Soviet Union collapsing, the Internet getting started, and hip hop going worldwide, two curious scientists ran some experiments that produced some very surprising implications for the twenty-first century.

The first of these was Scott J. Dickman, a doctoral student working in the Brain, Cognition, and Action Laboratory at the University of Michigan.

One month in 1985, Dickman carried out a series of three experiments. Before the experiments started, the participants took a standard test for the personality trait of impulsivity. Each person then sat down at a table with a deck of thirty-six cards in front of them. The cards, which were about the size of a smartphone, were each emblazoned with a large letter made up of smaller letters. On the command Ready, set, go! the participants completed three variations of the task: sorting the cards into piles based on the large letter, the small letters, or a mixture of both. The groups were asked to sort the cards as quickly and accurately as possible. Dickman expected the experiment to show that highly impulsive people would find it more difficult to complete the tasks. They would lack focus, struggle to ignore distractions, or fail to bring different information together. This was his expectation because that was the traditional view of both society and psychology. Impulsivity was seen as dysfunctional.

To his great surprise, people with high impulsivity scored as highly on the card-sorting tests as people with low impulsivity. Dickman couldnt explain his results, so he ran another set of experiments to try and figure out what was really going on.

This time he included colour as a third piece of information, to make the task harder and really emphasise the processing differences between high and low impulsives. People had to sort cards based on the big letter, the small letter and the colour. All groups had to combine relevant information, and ignore irrelevant information. Once again, the high impulsives did just as well as the low impulsives.

The mystery had deepened, and so had the value of solving it. To answer the question, Dickman proposed an original idea that some of the high impulsives used different strategies to low impulsives. They choose speed over accuracy, and, in this particular test, speed over accuracy led to results that matched those scored by low impulsives, who privileged accuracy over speed.