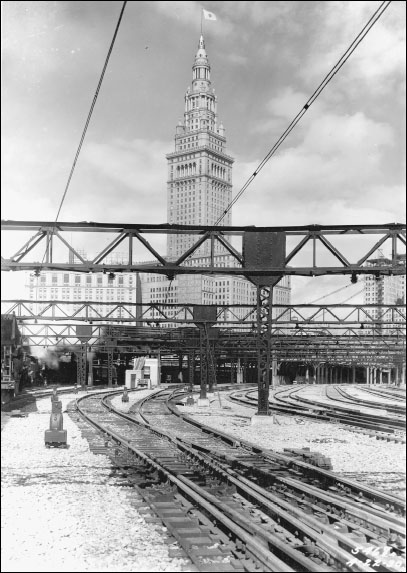

Cleveland Union Terminal was the greatest railroad station project in this corner of Ohio, and Terminal Tower still remains a distinctive part of the Cleveland skyline. More than just a railroad terminal, the Terminal Tower complex was built between 1926 and 1931 and eventually served the Baltimore and Ohio, Big Four, Erie, New York Central, Nickel Plate, and Clevelands rapid transit system. (Cleveland State University Library Special Collections.)

On the cover : Elyria was a major station on the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern (LS&MS) Railway in the early 1900s. In this c. 1907 view, passengers and their baggage await boarding. The depot was a typical 1870s design of the LS&MS repeated at many locations between Buffalo and Chicago. A track elevation project around 1925 led to the eventual replacement of this depot with a New York Centraldesigned passenger depot that still stands. (Mark J. Camp collection.)

Copyright 2007 by Mark J. Camp

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Without the assistance through the years of the following organizations this book would be much less complete: the Akron Canton and Youngstown Historical Society, Akron-Summit County Public Library Special Collections Department, Allen County Historical Society, Amherst Historical Society, Andover Public Library, Ashtabula County District Library, Ashtabula County Genealogical Society, Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland State University Library Special Collections, Conneaut Public Library, Conneaut Historical Railroad Museum, Elyria Public Library, Erie Lackawanna Historical Society, Geneva Public Library, Lake County Historical Society, Morley Library Genealogy and Local History Room, the New York Central Historical Society, Nickel Plate Historical and Technical Society, Oberlin College Library, Peninsula Library and Historical Society, the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library Local History Department, University of Toledo Carlson Library, Western Reserve Historical Society of Cleveland, and all the libraries and associations of northeast Ohio that maintain historical collections. Among the individuals that I owe a debt of gratitude for contributions to this book are Howard Ameling, Charles Bates, Randy Bergdorf, Robert Chilcote, Richard J. Cook, John B. Corns, John Eles, Carl Thomas Engel, Charles Garvin, Herbert H. Harwood, Clyde Helms, Kirk Hise, John Keller, Robert Lorenz, Willis A. McCaleb, Dave McKay, Max Miller, Phil Moberg, David P. Oroszi, Paul W. Prescott, John A. Rehor, Robert Runyan, W. C. Thurman, and Bruce Young. Some contributed photographs and historical data, others published articles and books that aided in the research, and others provided inspiration, leadership, and friendship over the years. Some are gone now, but their memory lives on in their pictorial recordings of railroad history. I also greatly appreciate the assistance of Kevin Capurso of the University of Toledo during the research and the scanning of photographs.

Historical information for this book came from Reports of the Ohio Railroad Commission , Annual Reports of the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio , Poors Manuals , Railroad Gazette , Railway Age , and other trade journals; The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Centennial History of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company 1846-1946 ; various newspapers of northeast Ohio; numerous centennial, bicentennial, and sesquicentennial compilations and histories of northeast Ohio communities; and firsthand interviews conducted over the last 40 years.

INTRODUCTION

Northeast Ohio was destined to become a major transportation corridor in the 1850s; it was directly in the path of railroads stretching westward from eastern markets to Chicago. Some of Ohios earliest railroads were projected to connect Lake Erie with the Ohio River and points south. Painesville, Ashtabula, and Conneaut each had competing plans. Cleveland, already a major lake port and canal port, sought to connect to larger cities across the Midwest. By 1900 the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway (LS&MS) and New York Chicago and St. Louis Railroad paralleled the Lake Erie coast on their way to Buffalo and Chicago; further south the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) connected Pittsburgh with Chicago, as did the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the Erie Railroad ran between New Jersey and Chicago. Like spokes of a wheel, the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis, LS&MS, New York Chicago and St. Louis, B&O, Pennsylvania, Wheeling and Lake Erie, and Erie Railroads spread away from downtown Cleveland, the railroad hub of northeast Ohio.

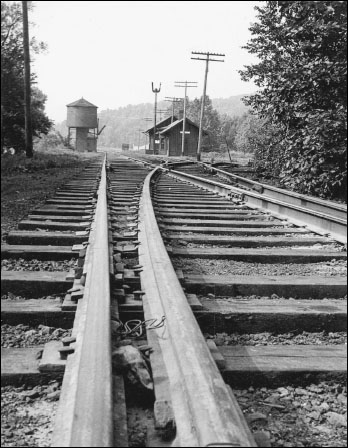

The railroads established stations at regular intervals along their lines to serve the traveling public and shippers; to provide necessary water and fuel for locomotives; to provide repairs for motive power; and to provide transfer facilities with other lines. Stations that served particular towns, or around which a community grew, became the sites of depotsshelters for passengers and freight and the railroad staff responsible for overseeing this business. Northeast Ohio communities became the sites of some 125 depots, busy debarking points for the traveling public, businessmen, professionals, and servicemen from the late 1800s to the 1950s. The typical railroad depot was a frame or brick structure with a waiting room on one end and a freight room on the other end with an office in between. This was known as a combination depot and was commonly erected in communities where business was anticipated to be moderate but not to the point of overtaxing the facility. Each railroad had a set of plans for the building of depots by their construction crews. Unique architectural features often distinguished depots of a particular line, but some features and props were common to most depots. These included a vestibule or bay window in the central office area that extended trackside, allowing the agent or operator a clear view up and down the tracks. Extended eaves provided protection to passengers standing along the loading platform on the trackside of the building. In larger combination depots the waiting room was divided providing separate waiting areas for women and children and men. Ticket counters connected the office area to the waiting room(s). Wooden benches and a potbelly stove were part of the decor of waiting rooms for many years. The office area contained the telegraph, which, before the telephone, was the connection of many a small community to news of the world. A timetable rack, station clock, typewriter, rubber stamps, and railroad calendar were standard equipment in the early years. Often a lever in the bay window would allow the operator to adjust the order board, a semaphore-like signal on the trackside of the building, to indicate to the train crew whether they had passengers or a message of importance to be retrieved at the depot. Mail bags and baggage and freight wagons also had to be strategically placed on the platform for stopping passenger trains so the transfer was quick and efficient. The freight room was usually unfinished, unheated, windowless, equipped with wide or double doors, and open to the rafters. The floor and platform were sometimes at a higher level to allow easier transfer of items to boxcars spotted on a depot siding, often behind the building. Depots had the name of the station clearly displayed on the ends of the buildings, either stenciled directly on the walls or on a separate town board. Some lines also displayed the name on the trackside of the depot or attached to a post along the loading platform. Larger communities and those that were deemed more important by the railroads, like county seats or junction points, often had separate passenger and freight depots. These were designed by railroad staff or by architectural firms employed by the railroads. Growths in passenger and freight business sometimes led to the replacement of combination depots with separate larger structures. Union depots were built where more than one line served a community and the railroads agreed to share a facility.