I The Urge to Draw

Almost everyone has, or has had, the urge to draw. Many adults have forgotten it, but drawing once came to them as naturally as eating. While some, to be sure, are more creative and articulate than others, every child draws. He keeps at it until with advancing years he becomes acquainted with the sophistication of professional drawing, grows self-conscious and discovers that he cant draw. That is very sad! If someone had been around to disabuse him of that notion he might not have had to wait until becoming a grown man to realize how mistaken that idea was. Now, at an advanced age, whether twenty or sixty, the primitive urge often breaks out. He sees a lot of people now drawing and painting for no other objective than the fun of doing it; just as many are playing musical instruments with no thought of profit other than joy to their souls.

And what profit can be more satisfying than that? Today, more and more people are practicing some form of art for just that reason. They have nothing to sell; they have no customers to please other than themselves. However, they are not necessarily easy to please; as a matter of fact they can, in time, come to be pretty tough customers, increasingly demanding of their own creativeness and skills.

Drawing, as we have said, is an instinctive human expression. The impulse to draw is actually the first point of difference between the human child and animal young with which his unconscious development has grown apace. It is the first sign of creativity. Drawing of course is universally practiced by primitive people. With them it may not be an intentional art form, though often, perhaps inevitably, it becomes that. Those marvelous prehistoric pictures painted on the walls of caves were, we are told by students of anthropology, created to serve the most practical needs; pictures of the hunt, for example, being in effect either prayers for the hunters success in the field, or the celebration of it. Also, then as now, picture images had their function in the practice of religion. In Egyptian art we can see how pictures were the origin of nonrepresentative symbols that eventually became the characters with which abstract thoughts could be expressed.

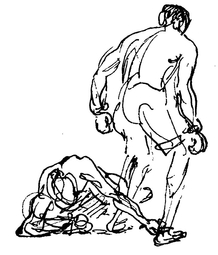

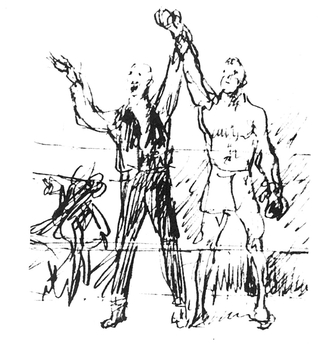

Action drawing from a Disney film.

But the development of abstract symbols has not lessened the usefulness of pictures in the communication of ideas and the expression of those imponderables which are beyond the reach of speech and letters. Music, the dance, handicraftsall art forms are in this category of communication through feeling and experience. Even bodily gestures are a form of drawing; they convey in motion an emphasis beyond the power of verbal expression. We all have imponderables to express in one or more of these arts; even in so simple an act as the drawing of a flower we release some part of our potential creativeness, which otherwise would remain imprisoned in our subsconscious. The person who has not experienced this kind of emotional release has no conception of the power there is in it for pleasantly transcending the day-by-day impact of mundane affairs. This is true no matter how amateurish the drawing may be. It is in the doing of it rather than in the result. From this point of view drawing is not necessarily an endowment of culture. That is proved by the uninstructed drawings of children. Even the crudest drawing, if it is done with feeling, becomes a significant contact with reality.

We have much to learn from children. They draw and paint without the fear that often grips the adult beginner, hesitant to put down his first stroke on paper. The expression there is nothing to fear but fear itself made memorable by a former president of the United States, applies to the early efforts of any student. When a layman is urged to take up picture-making in any form he may exclaim, Why I cant even draw a straight line! not realizing that drawing a straight line is seldom expected of him unless he is thinking of a very mechanical kind of delineation. The saying is merely a symptom of a general fear that he cannot draw anything at all. Thus the fear complex is the first stumbling block to be overcome. The conquering of that fear is the initial victory to be won. It can be achieved very quickly by the determination to spoil, intentionally, a great deal of paper. Start with the cheapest paper and the cheapest material. Just splash around with charcoal, ink, or crayonany material at all. Dont even try to make a decent drawing, merely get acquainted with the feel of your medium and discover something of its nature. For example, with a stick of soft charcoal make rapid sketches of any object in the kitchen or a spray of flowers from the garden. Work on a large scale at first, using arm movement rather than finger movement. The results will be startling from the viewpoint of expression even though lacking accuracy in delineation of form. This is a limbering-up exercise that will give confidence and help to abolish timidity.

A brush and ink drawing by Kane Tanyu, famous Chinese artist who died in 1746.

Spontaneous brush and ink drawing by Ora Edwards, contemporary American, whose drawings of children are noteworthy.

Drawing by Laszlo Krauss, an orchestra conductor who calls drawing his second love. This is a sketch of a musician in his orchestra.

Ballet Dancer Tying Her Shoe, by Edgar Degas, French, 1834-1917.

Detail of an on-the-spot sketch by the late Mahonri Young, a famous American sculptor, 1877-1957. Although he drew and sculptured the human figure with great perception and skill, in this sketch he merely recorded a rapid note to be used later, perhaps in a finished work.

One cause of the beginners timidity is the notion that without the ability to draw what he sees with precision and accuracy, his drawings have little value. A precise drawing can indeed be good; but precision, far from being an inevitable virtue, is often less inspired than an impulsive sketch that succeeds in endowing the subject with life. A fine example of this is the quill pen drawing of a lion by Eugne Delacroix (page 74), who could be very precise when he wished. Hendrik W. Van Loon, on the other hand, couldnt be precise. Although not a professional artist he could and did draw with both expression and information. He filled his books with sketches that give delightful graphic accompaniment to his written words even though they display lack of technical mastery. One might characterize his sketches as graphic gestures. (See his book The Arts, Simon & Schuster, 1937).