Contents

Page List

EFFORT

A BEHAVIORAL NEUROSCIENCE PERSPECTIVE ON THE WILL

EFFORT

A BEHAVIORAL NEUROSCIENCE PERSPECTIVE ON THE WILL

Jay Schulkin

Department of Physiology and Biophysics

Center for Brain Basis of Cognition,

Georgetown University

Copyright 2007 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher.

First published by

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers

10 Industrial Avenue

Mahwah, New Jersey 07430

This edition published 2012 by Psychology Press

Psychology Press Taylor & Francis Group 711 Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 | Psychology Press Taylor & Francis Group 27 Church Road Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA |

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schulkin, Jay.

Effort : a behavioral neuroscience perspective on the will / Jay Schulkin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8058-6009-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0-8058-6010-X (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Brain-Physiology. 2. Motivation. I. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Brainphysiology. 2. Motivation. WL 300 S386e 2006]

QP376.S355 2006

Dedicated to Heidi Byrnes, Micah Leshem, and Hal Pashler

Contents

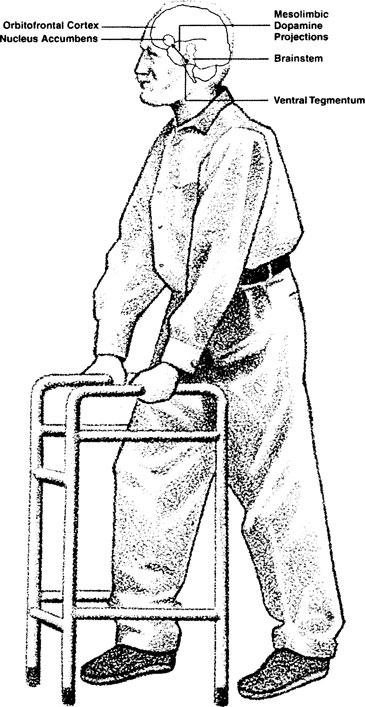

The diverse senses of effort are fundamentally linked to motivation, behavioral inhibition, self-regulation, and staying the course for long-term goals despite short-term seduction. One neurotransmitter that underlies the diverse senses of effort is dopamine; this is made apparent in Parkinsons patients, but it is also apparent in most of our everyday activities, whether we are still (e.g., solving a problem in our head) or moving about.

The core thesis is twofold: Central dopamine underlies diverse tasks, and there is no absolute separation of the cognitive and noncognitive brain; there are diverse cognitive systems many of which are embodied in motor systems that underlie self-regulation.

The scientific literature abounds with studies of decision making and effort. One approach is to demythologize our understanding of cognitive systems; the effort that we exert when we think, and either move or not move through space with our bodies, reflects the cognitive machinations in the brain; aberrations of brain systems reflect the breakdown in the long- and sometimes short-term goals that serve our well-being.

The classical pragmatists have had a significant influence on my thinking and my work. William James, for example, emphasized the importance of the effort within a psychobiological context and the feeling of effort as an important part of our experience. James places the understanding of the will within the context of the organization of action.

This book cuts across disciplinary lines. As always, I thank my family, friends, and colleagues for their help.

The 17th-century philosopher Spinoza (1688, 1955) put it this way: Everything endeavors to persist in its own being (p. 136; see also Heidegger, 1979; Nietzsche, 1883/1961). Effort or the will is the striving that everyone experiences; it is often a state of unrest and disquiet (Schopenhauer, 1818/1958). In small children, for example, a will to livestriving and stretching, responding to discrepancies and salienceis readily apparent (Kagan, Kearsley, & Zelazo, 1978, 1980).

Darwin (1859/1958), of course, emphasized self-preservation and survival. The fight to stay alive and the origins of our intelligence are at the heart of our evolution, both biological and cultural.

Effort is a term closely associated with motivation; will is traditionally linked to the effector systems tied to ones goals and intentions. But in fact, effort is tied to ones goals and intentions. Although these two terms are not identical, there is sufficient overlap for my purposes that in the context of this book they will often, though not always, be used interchangeably.

What do I mean by effort or the will? One recurring feature of what I have in mind is staying the course. Staying the course, staying steadfast to what one wants requires energy, powereffort or willpower. The athlete awakens to swim at 4 a.m., tired but committed to a longer term goal of competing and winning, or placing well. The structure of her life is oriented toward that end. She wants to go back to sleep, but she perseveres.

WILLIAM JAMESDIVERSE SENSE OF EFFORT

The will, as James (1890/1952) suggests, permeates motor systems: The will appears in every muscle as irritability (vol. 2, p. 252). By irritability, I take it, he should mean just activation, which might entail motivation and approach behaviors, behavioral inhibition, restraint, and limiting choice and action, all of which reflect cognitive systems that underlie behavior.

Striving in muscular activity is phylogenetically ancient; therefore, one fundamental sense of the will is expressed in evolution through bodily expressionbasic strivings. From a biological point of view, the issue has been addressed as a craving for life, a desire to persevere.

James (1897) characterizes effort and the will in terms of anticipatory cognitive regulation of motor systems (; Elsner & Hommel, 2001; Evarts, 1973) in the context of the burgeoning conception of neuronal functions. I suggest in later chapters, and have adumbrated here, that cognition need not be separate from motor control; there is no absolute separation of the cognitive systems from the motor systems. Many motor type functions are tied to cognitive expression (syntax production) and a number of traditional motor areas are now known to be tied to cognitive functions (parts of the basal ganglia; Parent, 1996; Ullman, 2004).

The kinesthetic idea, as James liked to put it, is basic to our concept of the will. The use of bodily force and the feeling of effort were critical markers of the will. The continued ability to resist or to pursue is a marking of the willa body extended in space (Bain 1859/1886; Dooley, 2001; Ingvar, 1994). James outlined a view in which the sense of the will was knotted to diverse forms of action (Kane, 1995)cognitive systems no less than overt behaviors (Frese & Sabini, 1985; Frijda, 1986; Gollwitzer, 1996; Jabre & Salzsieder, 1997; Spence & Frith, 1999). Effort, I suggest, is just one feature of what might be associated with the will, and even that might vary depending on the task ()

FIG. I.1. Effort in one of its many forms: battling Parkinsons Disease.

James, who was trained as a physician and taught psychology, was aware of the advances in the biological and neural sciences, and his philosophical orientation reflected these facts. James (1890/1952) made reference to the findings of Darwin and Jackson, Ferrier and Lamarck. He understood that bodily reactionsor simple reflexes, as Dewey (1896), his fellow pragmatist, also notedare replete with ideation: ideas embodied in bodies in action. Minds are not spectators on the sidelines. This is what James and others (e.g., Lotze, 1852; see also Jeannerod, 1994) called idea-motor reflex. In other words, cognitive systems pervade human action, and human action is permeated by diverse goals (Prinz, 2003).