A frica and the D iaspora

History, Politics, Culture

S eries E ditors

Thomas Spear

Neil Kodesh

Tejumola Olaniyan

Michael G. Schatzberg

James H. Sweet

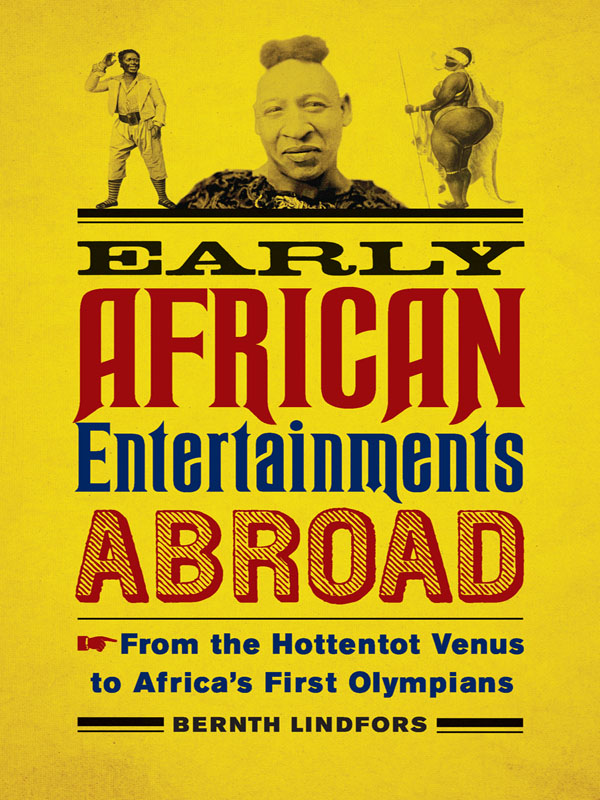

Early

African Entertainments

Abroad

From the Hottentot Venus

to Africas First Olympians

Bernth Lindfors

The University of Wisconsin Press

Publication of this book has been aided by a College of Liberal Arts Subvention Grant awarded by The University of Texas at Austin.

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

London WC2E 8LU, United Kingdom

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2014

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any format or by any meansdigital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rights inquiries should be directed to .

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lindfors, Bernth, author.

Early African entertainments abroad: from the Hottentot Venus

to Africas first Olympians / Bernth Lindfors.

pages cm (Africa and the diaspora: history, politics, culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-299-30164-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-30163-7 (e-book)

1. AfricansEuropePublic opinionHistory.

2. AfricaIn popular culture.

3. Blacks in popular cultureHistory.

4. Racism in popular cultureHistory.

5. Sideshows.

I. Title. II. Series: Africa and the diaspora.

DT16.5.L57 2014

791.0899604dc23

2014007282

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

The essays collected here originally appeared in whole or in part in the following publications and are reprinted with permission as noted.

Courting the Hottentot Venus, Africa (Rome) 40 (1985): 13348.

The Afterlife of the Hottentot Venus, Neohelicon 16, no. 2 (1989): 293301. Reprinted with permission of Springer.

The Bottom Line: African Caricature in Georgian England, World Literature Written in English 24 (1984): 4351.

Ira Aldridge at Covent Garden, April 1833, Theatre Notebook 61, no. 3 (2007): 14463. Reprinted with permission of Trevor Griffiths, editor of Theatre Notebook.

Clicks and Clucks: Victorian Reactions to San Speech, Africana Journal 14, no. 1 (1983): 1017. Copyright by Africana Publishing. Reprinted with permission of Lynne Rienner Publishers on behalf of Africana Publishing.

Seeing the Races Through Zulu Spectacles: Victorian Cultural Attitudes in Modern Times, Anglistik & Englischunterricht 16 (1982): 10717.

Charles Dickens and the Zulus, African Literature Today 14 (1984): 12740, a journal edited by Eldred Jones. Reprinted with permission of James Currey, an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd.

A Zulu View of Victorian London, Munger Africana Library Notes 48 (1979): 119.

Hottentot, Bushman, Kaffir: Taxonomic Tendencies in Nineteenth-Century Racial Iconography, Nordic Journal of African Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 130. Reprinted with permission of Axel Fleisch, editor of Nordic Journal of African Studies.

Dr. Kahn and the Niam-Niams, tudes Germano-Africaines 6 (1988): 2736.

The United African Twins on Tour: A Captivity Narrative, South African Theatre Journal 2, no. 2 (1988): 1641. Reprinted with permission of Petrus du Preez, editor of South African Theatre Journal.

Circus Africans, Journal of American Culture 6, no. 2 (1983): 914. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

P.T. Barnum and Africa, Studies in Popular Culture 7 (1984): 1827. Reprinted with permission of Rhonda V. Wilcox, editor of Studies in Popular Culture.

Africas First Olympians, West Africa, August 6, 1984, 157577.

Several of these essays have been reprinted in edited volumes and in collections of my own writings. All of them have been revised and updated to some extent, and they are brought together here as contributions to the study of racial stereotypes in popular culture, particularly as manifested in characteristic verbal and visual responses to African performers in England and America in the nineteenth century. However, given the similarity of some of the individuals and groups represented as well as the circumstances in which they were originally presented to the public as related subjects in a series of discrete studies on a common theme, it has proven difficult to avoid occasional repetitions and redundancies altogether. I accept full responsibility for such infelicities.

I am grateful to the libraries and publications cited for permission to reproduce the images that illustrate the essays. I also wish to thank my daughter Susan for helping with the index and my daughter Brenda for photographing some of the images. In addition, I am grateful that publication of this book has been aided by a College of Liberal Arts Subvention Grant awarded by The University of Texas at Austin.

Early African Entertainments Abroad

Introduction

L ong before Darwin, European scientists were wrestling with the question of mans relationship to other living creatures. In the Great Chain of Being that was presumed to link all forms of sentient life, man was thought to stand midway between the apes and the angels, a favored if somewhat ambiguous position that made him both animal and spirit. But just as there were different species in the animal world that could be arranged in a hierarchical order of supremacy, so were there different varieties of men and women who could be classified as inferior and superior types and placed accordingly on a graded scale of innate ability. In the animal world Homo sapiens obviously lorded it over the rest, and in this supreme category European man was considered at least by European mento be at the very pinnacle of earthly creation. It may have been the scientists preoccupation with taxonomic tidiness that led logically to the postulation of an absent transitional figure or missing link that was believed to have served as a direct genetic connection between men and brutes.

Some scientists, of course, were of the opinion that the link was not missing. By calling attention to the close resemblance of the lowest men and women to the highest apes, they sought to prove that the great chain was intact and unbroken. In their theories non-Western peoples, particularly Africans, were cited as examples of debased creatures sufficiently different in mind and body from European peoples to constitute a separate and unequal branch of the human family, if indeed they deserved to be called human at all. Charles White in An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man and in Different Animals and Vegetables (1799) concluded that the African, more especially in those particulars in which he differs from the European, approaches to the ape [and] the characteristics which distinguish the African from the European are the same, differing only in degree, as those which distinguish the ape from the European. Africans, whether manlike apes or apelike men, belonged at the bottom of the ladder and were the lowest anthropomorphic link in the great chain.