INTRODUCTION

CHICANO LIFE AND COMMUNITY, LIKE VIRTUALLY ALL CONTEMporary sociohistorical communities and their particular events and movements, have been extensively photographed. Fixed and moving images of whatever realm of contemporary life are so absolutely overwhelming, and casual materials, journalistic reportages, and formal cultural production are so abundant, that it is often difficult to know where to begin in assembling a sample of illustrative material. And as United States Latinos move more and more into the American mainstream, coverage intensifies, often bringing into question the extent to which it makes any sense to hold on to ideological or ethnic boundaries. Concomitantly, the sheer volume of artistic production generated by those who self-identify as United States Latinos, or Hispanics, or Mexican Americans, or Chicano, as well as an impressive range of alternative designations, has now generated a significant infrastructure of critical institutions and scholarship.

Yet it is striking that major sources on Chicano cultural production, to which I will now essentially refer, since it is the focus of this monograph, have emphasized production in the plastic arts and rarely include photography as an important cultural genre, despite how much of Chicano life has been captured in the multiple languages of photography. The last major exhibition of Chicano art, represented by the catalog Phantom Sightings (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2008), contains very little in the way of photographic texts. The exhibition was significantly identified as directed toward the enormous visibility of Mexican Chicano life after the monumental Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, which struggled so much

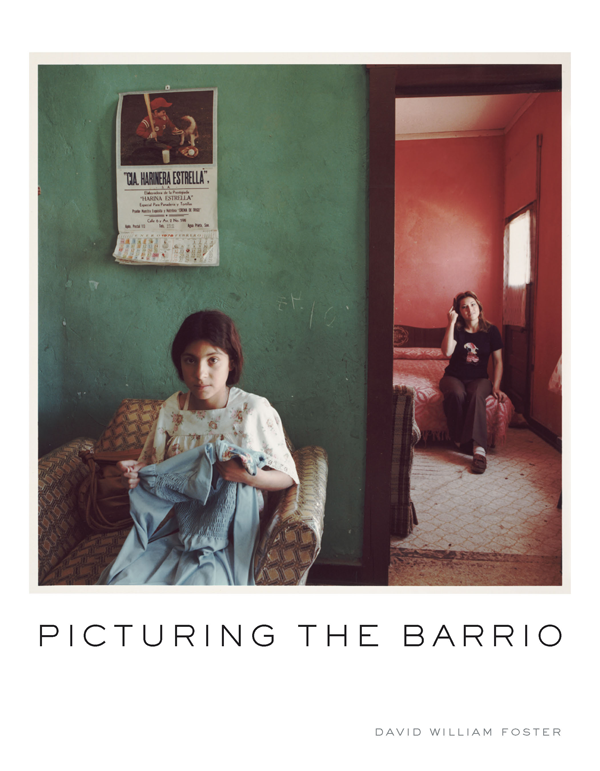

This study, in fact, originally set out to concern itself with United States Latino photography in general, with no particular restrictions in mind, except to deal with the most innovative work discoverable. However, it quickly devolved into an investigation of Mexican American and Chicano artists as a consequence of the natural preponderance of the material uncovered with the other controlling parameter, which was that the photography must have been published in book form (exclusive of collections such as Horacio Fernndezs, which, by the way, includes no United States Latino artists). This criterion, it was felt, would ensure in some measure that focus would be only on the most recognized quality work and that the work would generally be more bibliographically available than would be the case with a reliance on websites and their attendant vagaries. The discovery of ten major artists whose work was available in this fashion quickly established the basic inventory, which then revealed that the predominant interest was on urban social and cultural issues. Such an emphasis is understandable when one considers how the history of the Chicano community has been marked by its increased urbanization, especially in the American Southwest, where the rural and farm roots that were so much a part of the Chicano Movement gave way to barrio life in major cities to one degree or another. But the barrio/rural disjunction cannot be an absolute one. After all, many of the traditional ways of life preserved in the barrio have their roots in a rural existence, and aspects of barrio life have much that can be viewed as resistance to or critical response to the larger urban contexts in which the barrio is to be found. Yet there can be no question that the photographic record that comes together in these chapters often privileges the hegemonic urban nature of contemporary American social life beyond the particularities of ethnic divisions.

My interest in the analysis of this photographic record can be calledideological and semiotic. I am interested, as a scholar of photography, in attempting to understand what gets photographed and how it situates itself in terms of overall processes of cultural self-understanding. It is not so much a question of what photographs tell usbecause all photography is really an exercise in narrativitybut how they tell what they tell. To be sure, this means attending to technical questions of style and artistry, but processes of meaning are not circumscribed by the strategies and techniques of art, and have to do rather with fundamental questions of who produces meaning in a cultural text, how we go about knowing what that meaning is, and how we situate it within the sociohistorical circumstances from which cultural products arise. A photographer may have a particular story to tell and a particular range of materials with which to tell it. But the processes of meaning are independent from artistic intention in many important ways, and what actually gets toldwhat actually gets read by the viewer who validates the existence of a photograph at any one specific point in timegoes beyond artistic intention and, therefore, authorial containment. My readings are thus only one viewers interaction with the texts, although it is hoped that this is a significantly cogent and informed interaction to suggest, at least, to other viewers why they should take this photography as serious artistic achievement. My goal is neither to establish a canon of Mexican American/Chicano photography nor to promote certain uses of photography. It is, instead, I hope, an intelligent account of varieties of photographic enterprise in current Mexican American cultural production that focuses on what has come to be defined as the Chicano experience. A particularly thorny issue is the decision whether to use Mexican American or Chicano as the defining adjective of this study. The argumentshistorical, ideologicalin favor of one or the other are both complex and contentious. Neither term is appropriate for the public self-identity of all the artists represented here: Louis Carlos Bernal, for example, belonged to a generation that was more likely to self-identify as Mexican American; Miguel Gandert, whose overall work has focused on Hispanic life in New Mexico, is more aptly characterized by the term Nuevomexicano. In the end, however, I chose to go with the term Chicano, both because it is now the most generalized academic usage and because it was the 2008 Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition Phantom Sights: Art after the Chicano Movement, with its virtual absence of photography, that initially prompted this scholarly inquiry. Moreover, since the nature of the photography examined here is its emphasis on the Chicano experiencebarrio life; the sense of cultural pride and identity; a nostalgia for historical modes of individual and community life, especially that brought by forebears from Mexico; a critical stance toward the promises of the American dream; the denunciation of the injustices of the American way of life; and an overallcommitment to dominant icons shared by those who are recognized and who self-recognize as making up the Chicano community. Thus, for example, even when Gandert does not self-identify as a Chicanoand even when so much of his photography deals with Novo-Mexican themeshis photography on mariachi music in Los Angeles, with reference to one of the icons of Chicano life in that city, the so-called Hotel Mariachi, allows us to include this body of work within the rubric of Chicano.