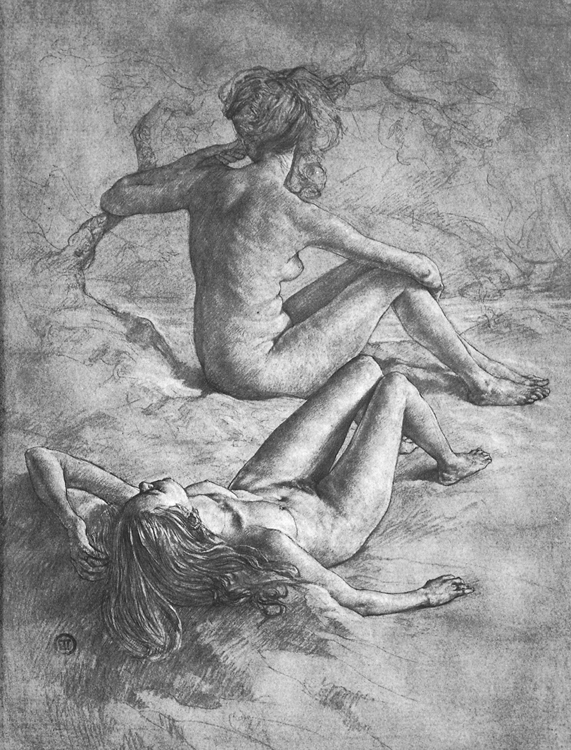

(frontispiece)

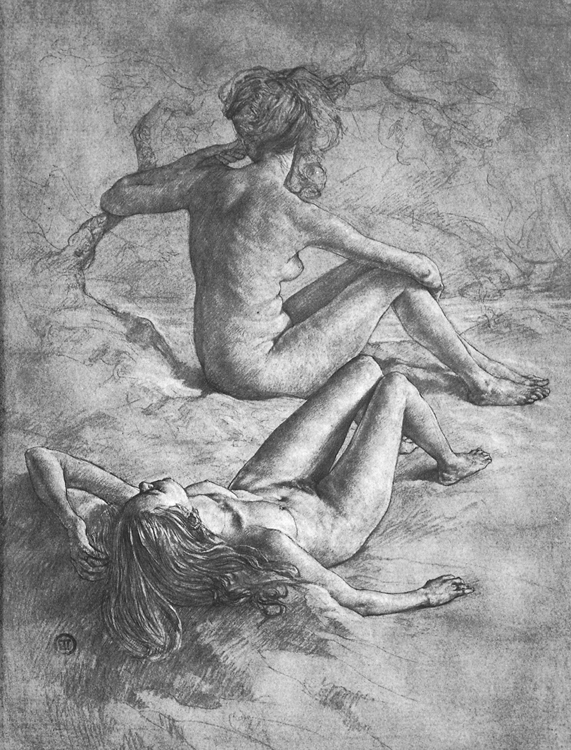

T WO W OMEN BY A B ROOK

Sepia lead charcoal and pastel tinted paper.

24 by 18 (60.9 45.7 cm). 1985.

Drawing

WHAT THE

Eye Sees

TED SETH JACOBS

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

To all my fellow students in the pursuit of light, in the hope that they have learned as much from me as I have learned from all of them.

Copyright

Copyright 1986 by Ted Seth Jacobs

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2013, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Watson-Guptill Publications, New York, in 1986 under the title Drawing with an Open Mind: Reflections from a Drawing Teacher.

Fine-art photography by Nathan Rabin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jacobs, Ted Seth.

[Drawing with an open mind]

Drawing what the eye sees / Ted Seth Jacobs.

p. cm.

Summary: Heralded as a revolutionary right-brain approach to figure drawing, this guide focuses on mentality rather than technique. The author presents personal reflections and advice on drawing what the eye sees instead of what the mind dictates. More than 180 black-and-white drawings and eight pages of color illustrations reinforce such concepts as light, balance, and symmetryProvided by publisher.

This Dover edition, first published in 2013, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Watson-Guptill Publications, New York, in 1986 under the title Drawing with an Open Mind: Reflections from a Drawing Teacher.

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-31575-1

1. DrawingTechnique. I. Title.

NC730.J23 2013

741.2dc23

2013014055

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

491064012013

www.doverpublications.com

I would like to thank the flowers and trees who posed uncomplainingly, various pieces of furniture that gave their opinions about life and art, old streets full of stories, musiciansimagine!who transform the air as we draw; generous human models, idealistic and courageous dancers, and, since we are all both teachers and students, everybody; but especially my reverent thanks for the incomparable shining gift of life.

With the exception of the schematic diagrams and three mythologic subjects done entirely from imagination, all the drawings in this book were executed completely from life.

Contents

Thoughts

About

Drawing

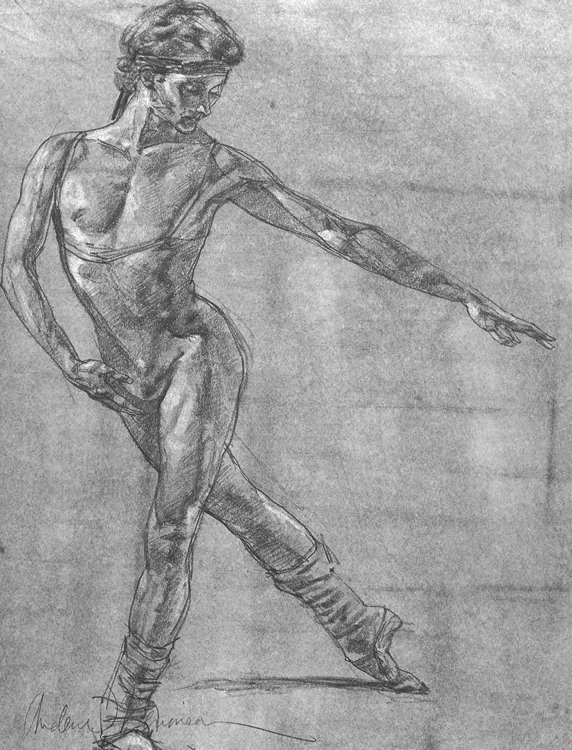

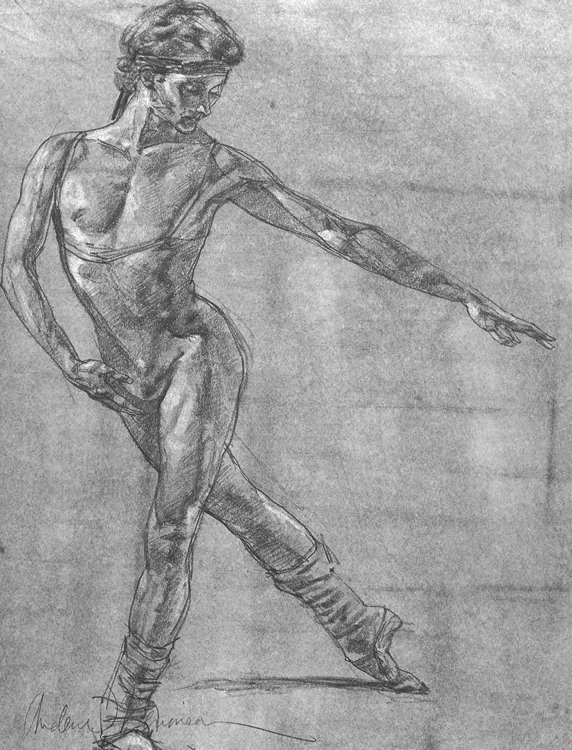

A NDREW L EVINSON

Sepia Cont chalk and pastel on paper. 20 14 (50.8 35.5 cm). 1982.

This drawing, and most of the other dance drawings presented in this book, are taken from the artists 1981 one-man exhibition The World of Dance at Coe Kerr Galleries, New York.

ABOUT DEFINING TERMS

ABOUT DEFINING TERMS

What is drawing? At first glance the question seems simple enough to be superfluous; but upon reflection it becomes not only difficult, but perhaps not even definable.

Suppose an answer is given as, Marks on a surface, representing something. Although the first part of that answer doesnt seem to present any problems, the second part does. Do marks need to represent something in order to be qualified as drawing? Even if within the term something can be included the broadest inferencessuch as an idea, a representation of something seen, a moodit can be argued that the marks need not represent anything, that in their graphism, independent of all association, they constitute drawing. If that definition is accepted, how can drawing be differentiated from any other form of marking? As an extreme instance, can we say that footprints are or are not a form of drawing? I recall seeing an Indian dancer who put a staining agent on the soles of her feet, and during the course of her dance upon a stretched cloth, produced a stylized drawing of a peacock. If that is drawing done by a dance, are footprints a drawing done at a walk? The problem is that any definition seems either too exclusive or inclusive. The term drawing possibly cannot be defined. If it is indeed impossible to define terms, I wonder whether it is necessary to do so. What compels us to define? Is it habit, an approach to thought that urges us to define something before discussing it? If define we must, ought we, on the basis of all the ideas that arise around the subject, allow a definition to suggest itself? But without a definition, how can we know the subject of our speculations, out of which we hope to realize a definition?

These questions may sound sophomoric, but they in fact infest the roots of our thought processes, the relationship between thought and language, and, as I hope will become apparent, the deepest reaches of the process of drawing.

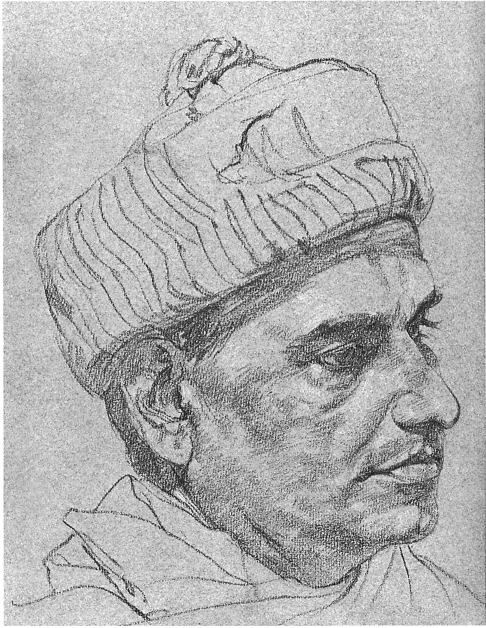

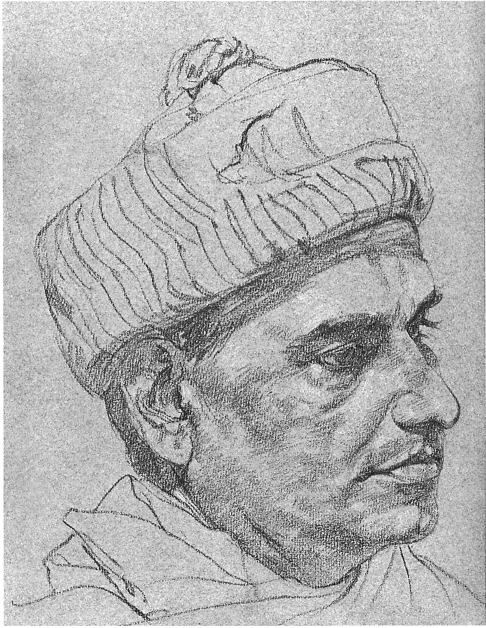

A NTUBHAI V EDYA , A YURVEDIC D OCTOR

Sanguine chalk on gray paper. 10 8 (25.4 20.3 cm). 1953.

When you draw from life, its easy to forget that what youre making is a drawing rather than a recreation of a person on paper.

THE DRAWING IMPULSE

THE DRAWING IMPULSE

Among the many things it may be, drawing is a trace, a track, a traillike the leak from an oil-line down a highway or the progress of the worm in the woodwork, the print, the fossilized remains of movement. Even the fish in the ocean, the free bird in the sky, draw an invisible arabesque after themselves. In this sense, drawing is the relic of movement.

Movement, it may be said, is the translation of intent into action. On the origins of intent and desire I will not presume, but surely desire is a cry from the deepest corners of our being. This way of considering drawing creates a linked progression through time. From urge to idea to movement to trace, or drawing. This suggests that everything stands for something anterior and other. But is it just as possible that the drawn stroke is the original urge? Then perhaps everything only, stands for itself. In this context, it is even conceivable that drawing may be the free-standing original impulse that subsequently generates conceptions which then pique to life the sleeping snake of desire. And for those of you who are not passionate partisans of logical systemics, drawing may be all of these coexisting simultaneously. But however much of all these things that drawing may be, it is, as we will see, much more.

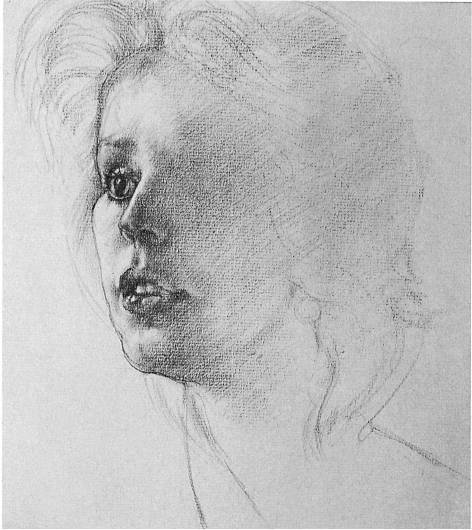

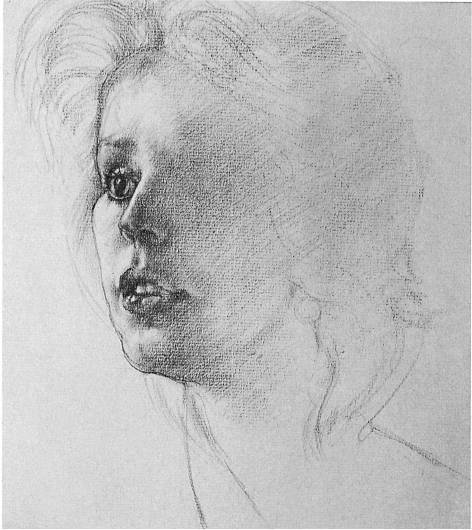

L AURIE L EVETTE

Sanguine lead on sand-colored paper. 1979.

Although it seems all to self-evident, drawing only suggests or symbolizes a perceived object; it can never recreate that object.

OUTLINE AND APPEARANCE

OUTLINE AND APPEARANCE

Drawing can suggest, represent, or symbolize perceived objects. But how in fact can this be possible? Of foremost importance when examining questions about representational drawing is the fact that the drawing is not and never can be the object it portrays. This appreciation seems so self- evident as to appear unnecessary, but it is honored by draftsmen more often in the breach than in the observance. When engaged with the difficulties of drawing from a model, the artist can easily forget that he is not indeed recreating that model on paper. It seems laughable, incredible that anyone may fail to notice that difference, but experience shows that an absorption in the drawing process can blind people to simple verities. When drawing, any form of blindness is undesirable, and this elementary lack of discrimination produces deformations in drawing.

Next page

ABOUT DEFINING TERMS

ABOUT DEFINING TERMS