TRACKING THE GOLDEN ISLES

Tracking the Golden Isles

THE NATURAL and HUMAN HISTORIES of the GEORGIA COAST

Anthony J. Martin

Publication of the book was made possible in part through a grant from the Emory College of Arts and Sciences and the Laney Graduate School.

Published by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

2020 by Anthony J. Martin

All rights reserved

Designed by Erin Kirk New

Set in 10 on 14 Chapparal

Printed and bound by Sheridan Books

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 C 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Martin, Anthony J., 1960author.

Title: Tracking the Golden Isles : the natural and human histories of the Georgia coast / Anthony J. Martin.

Description: Athens : The University of Georgia Press, [2020] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019052220 | ISBN 9780820356969 (hardback) |

ISBN 9780820356976 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Natural historyGeorgiaAtlantic Coast. | Barrier island ecologyGeorgia. | Barrier islandsGeorgiaHistory. |

NatureEffect of human beings onGeorgiaAtlantic Coast. |

Atlantic Coast (Ga.)Environmental conditions.

Classification: LCC QH105.G4 M37 2020 | DDC 508.758dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052220

To Richard Bromley and George Pemberton: May your cognitive traces continue to inspire those who read the earth and the stories inscribed by its life.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

We live in a world defined by traces. These signs of plant and animal behaviortracks, trails, burrows, nests, feces, rootings, borings, and much moretell many stories about our earth both past and present, blending together to bestow a sense of the history of life while also acting as harbingers of its future. But traces do not just pass on tales. Over the past 500 million years, they also actively shaped the skin of the planet and composed entire environments, from the deep sea to mountaintops.

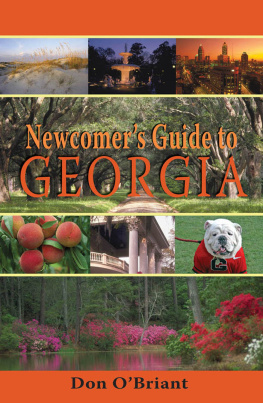

Where on earth would you go, then, to get a crash course in understanding the awe-inspiring and time-traveling power of traces? I suggest you take a trip to the Georgia coast and especially to take a look at its barrier islands. Although these islands are world famous mostly for reasons revolving around human affairs of a mere five hundred years or so, they deserve even more fame for their traces. Gaze on a salt marsh and behold a field of grass made possible by periwinkle grazing, fiddler crab burrowing and scraping, and mussel filtering. Stroll through a maritime forest and know the ground below teems with animal life hidden in burrows, as do trees both living and dead with their wood-boring fauna. Pass by the dunes alongside a beach and ponder how many future generations of sea turtles emerged from their sands, with mothers surviving more than thirty years at sea before coming back to those beaches and digging temporary homes for more of their kind. Scan a beach at low tide and note the thousands of tiny volcanoes that represent the tops of the vast tunnel systems dug by burrowing shrimp. Pick up an empty snail shell from that beach and examine its holes, healed breaks, and other markings to learn not only that it lived its life and died but also that its shell hosted other lives that went on epic journeys.

Curious? Regardless of whether you can or cannot physically go to the Georgia sea islands, this bookTracking the Golden Islesis intended to give a few appetizers of the traces there and the stories they tell. Having spent a good chunk of my life studying and teaching about plant and animal traces of the Georgia coast, I tried to share some of what I learned with others through a previous book, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast (2013). Yet after four years of working on that book, and as pleased as I was once I felt its considerable weight in my hands, it still felt oddly incomplete. More accounts were out there being written in the sand, mud, wood, shells, and bones of the islands, and each time I went to look for them, there they were, and they never failed to confer new insights. So in 2011, even before the predecessor to this book was published, I began writing some of these new lessons in a blog bearing its name, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast. Much of the book you hold now was birthed through that blog, an eight-year gestation that also includes updated information and new musings about the gorgeous natural places and biota of the Georgia coast.

Nonetheless, one of the realities of the coast I also try to convey with this book is how it is not all just cordgrass and crabs, and it is not a perfect time capsule of what once was. Because people have been a part of the islands and their ecosystems for more than four thousand years, these places are a broken mirror in which we can admire their beauty while also acknowledging their flaws. The first people on the islands, the probable ancestors of the Guale and Timucua, came voluntarily, and they left traces of their culture and cooperation. Much later, representatives of powerful institutions from Europe arrived, regimes that then waged wars of conquest and cultural assimilation that erased most of those who preceded them. Other people were later captured, enslaved, and forcibly shipped across an ocean, where the survivors of those brutal journeys worked island lands for the commercial benefit of the colonizers. Even after earning their freedom, these people, their former enslavers, and their descendants continued to change the islands and other nearby environments up to now and will continue to do so into an uncertain future. The newcomers also brought plants and animals that had evolved elsewhere but soon displaced native species and altered entire habitats.

All the while, though, ghost crabs punched holes into coastal dunes; woodpeckers drilled into live oaks and cabbage palms; raccoons dug up, ate, and defecated the remains of fiddler crabs; moles burrowed for and found earthworms to their liking; moon snails hunted hapless clams; and ghost shrimp plumbed deeply into offshore sands. No matter what happens next in our relationship with the Georgia sea islands and the uncertainty of massive changes already underway, we can be assured that traces remain and traces will be made, with new stories in process.

No book, whether about islands or not, is an island unto itself. So before celebrating scripts, human or otherwise, I must thank all who made this book possible. First, I appreciate my agent, Laura Wood (FinePrint Literary), for supporting my writing this book and for affirming University of Georgia Press as my first choice for a publisher. As a graduate of the University of Georgia (PhD 1992), writing for UGA Press felt like returning to my intellectual home and a rightful way to honor the place where I first learned about the Georgia coast.

Second, I want to thank the University of Georgia Press staff, particularly acquisitions editor Patrick Allen. In a geographically appropriate way, I pitched my idea for this book to Patrick in January 2018, as we both stood on Jekyll Island (Georgia) at the One Hundred Miles Choosing to Lead conference there. My gratitude also goes to other UGA Press staff: chief editor Lisa Bayer, for approving the book proposal; assistant to the director and editorial assistant Katherine La Mantia; intellectual property manager Jordan Stepp, for composing the book contract; and Jon Davies (project editor), Erin New (designer and compositor), and Melissa Buchanan (production coordinator), for helping make this book real. Two external reviewersone anonymous, and one not (thank you, Dr. Evelyn Sherr)provided helpful suggestions for improving my original proposal for the book and later convinced me of what should stay and what should go. The copyeditor, Susan Silver, was invaluable for polishing my prose and otherwise detecting oddities, inconsistencies, and just plain dumb mistakes, ensuring a more readable book. Of course, if you see anything amiss, factually or otherwise, thats on me.

Next page