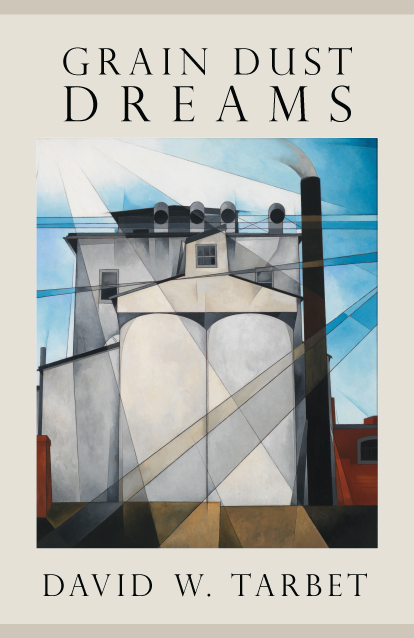

Cover: Charles Demuth, 18831935

My Egypt, 1927

3515/16 x 30 in. (91.3 x 76.2 cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 31.172

Digital Image Whitney Museum of American Art

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2015 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Excelsior Editions is an imprint of State University of New York Press

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Ryan Morris

Marketing, Kate R. Seburyamo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tarbet, David W., 1941

Grain dust dreams / David W. Tarbet.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5816-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4384-5818-2 (e-book)

1. Grain tradeNew York (State)BuffaloHistory. 2. Grain tradeOntarioThunder BayHistory. 3. Grain elevatorsNew York (State)BuffaloEmployeesHistory. 4. Grain elevatorsOntarioThunder BayEmployeesHistory. I. Title.

HD9038.B9T37 2015 |

338.1'7310971312dc23 | 2014045150 |

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated

to

my father

George Barclay Tarbet

Who worked many years in Thunder Bays Manitoba Pool 1

Foreword

This book about grain elevators combines three elements: two geographic and one personal. The cities of Buffalo, New York, and Thunder Bay, Ontario, each, at different times, held the title of the worlds greatest grain shipping port. Theyve earned their place in any book about terminal elevators. These arent the only cities with grain elevators, of course. What connects them is my personal experience, that is, the fact that Ive lived in both. I was born in Port Arthur, Ontario, and grew up in the twin city of Fort William. These two cities on the north shore of Lake Superior combined in 1970 to become Thunder Bay. That same year, by a roundabout route, I arrived in Buffalo.

Everyone living in Thunder Bay knows about the grain elevators and I knew them particularly well. My father worked in the Manitoba Pool 1 elevator. Pool 1 sits in a row of elevators ranged along Lake Superior in the intercity area that lay between Fort William and Port Arthur. I later took my turn at elevator work, but it was an earlier job with the Canadian National Railway that provided my first real introduction to the elevators. Railroads and elevators go together. Grain comes into the elevators in Thunder Bay from western Canada in railway cars. When a grain car arrives in Thunder Bay, it has to be accounted for, sent to the right elevator and, once emptied, the car has to be returned to the train yard to be sent west to be loaded again.

My uncle Art worked as a brakeman on the CNR and, when he told me the railroad was looking for car checkers, I jumped at the chance to get the job. It was a very good summer job for a high school kid, but you had to be sixteen to work on the railroad. I was fifteen. I got the job, but I kept putting off bringing in my birth certificate. When I did deliver it the next summer, the yardmaster looked at it for a while and handed it back to me without saying anything. I took that as a successful review of my first summers work.

A car checker keeps track of the railroad cars that sit in a switching yard. I started in the large CNR switching yard located in the intercity area not far from Manitoba Pool 1. In my first summer, I worked the midnight shift. At least once a night, I had to walk the length of all of the tracks in the yard. The tracks in a switching yard run off a lead track and the tracks get shorter as you move along the lead. The outside and longest track was always filled with empty boxcars waiting for their return trip west, and I had to take the long, dark walk beside it each working night. The light of the kerosene lantern I carried in the fold in my left arm would show a trail of grain along the ground beside the track. That loose grain had dropped from the empty boxcars as they were shunted in and out of the track. The kernels of grain looked more attractive to rats than to me. Every once in a while Id hear scurrying in the dark and would be glad that Id tied shoelaces tight around the bottom of my pant legs. I never really believed the stories that the switchmen told of rats running up your pant leg, but I didnt want to take the chance. They all go together: boxcars, elevators, grain, rats. And, yes, the fast-moving shadows under the boxcars were cats. But you wouldnt want to mess with them.

In the summer after my last year in high school, I was lucky to get a job at the Lakehead Planning Board. (Before Port Arthur and Fort William amalgamated, the two cities were collectively known as the Lakehead.) That job ended my connection with car checking and the CNR, so, in the summer after my first year at university, I had to look farther for a job. I found one in a grain elevator. The Searle elevator was located outside Fort William near the mouth of the Kaministiquia Riverknown locally as the Kam. Again, it was a good job that paid well and I didnt have to lie about my age to get it. Unfortunately, it didnt last long. I could put up with the noise of the elevator and I didnt mind the work. I could handle the job of shoveling up grain that had spilled from the conveyor belts and I could adjust the temperature in the dryers once I learned how to listen to instructions over the near-deafening noise of the drying machine, but I could not handle the dust.

Grain dust is everywhere in an elevator. Its a constant and unavoidable companion. For most, grain dust is annoying, causing red, itchy spots around the neck and elbows, but, for me, dust was a serious problem. I developed full-blown grain dermatitis. When I got home from work I filled a bathtub with cold water and lay in the tub until the itch I felt from head to foot went away. I thought I might get over it or that the problem would ease and I would learn to tolerate it, but the itch got worse. After two weeks, I told the elevator manager that I couldnt work in the elevator any longer; I collected a check for two weeks pay and left.

Many years later, I arrived in Buffalo. By then, I had graduated from the University of Toronto and had a PhD in English from the University of Rochester. From Rochester, I joined the English faculty at the State University of New York at Buffalo. I lived and taught in Buffalo for fourteen years and remember being impressed by the manythen largely abandonedelevators lining the Buffalo River. That impression, however, was peripheral. I saw the elevators on the Buffalo River out of the corner of my eye as I took my son fishing in a pond at the Tifft Farm Nature Preserve south of the city.