To Monk and Fisher

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2021

Copyright John Beck 2021

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789143065

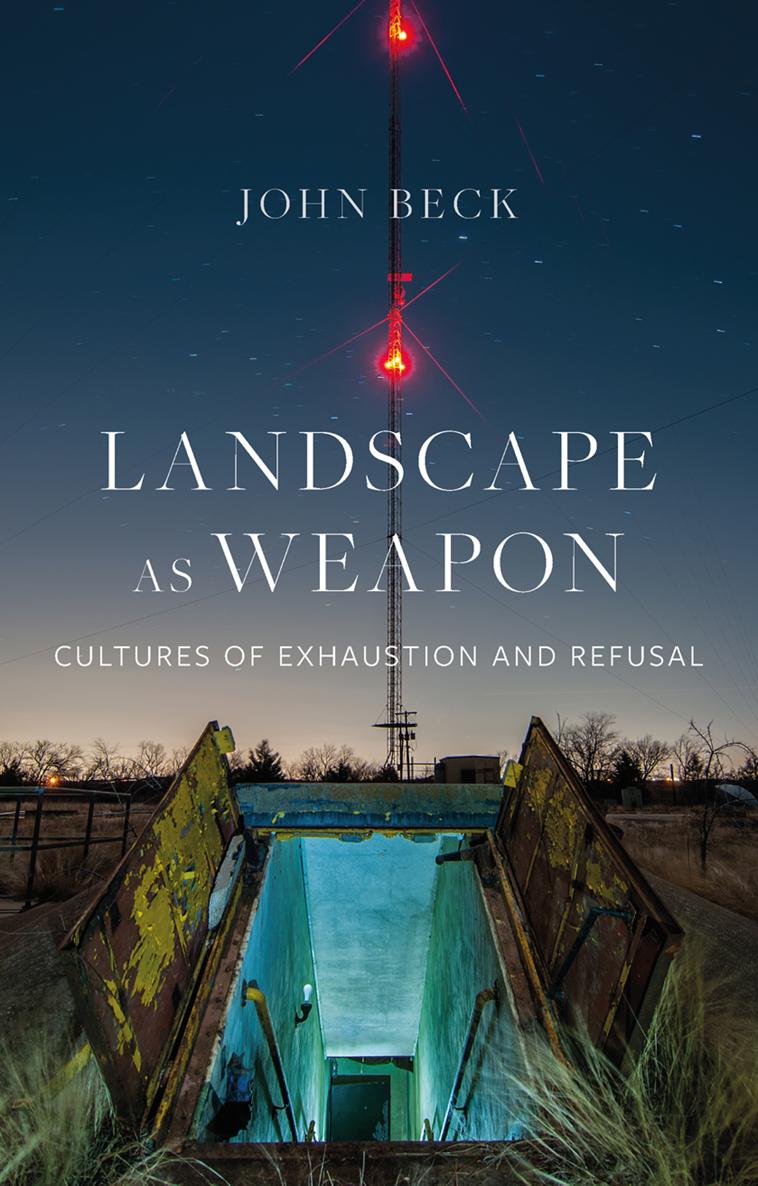

Introduction

In March 2019 a major new exhibition by British artist Mike Nelson opened in Tate Britains Duveen Galleries. Titled The Asset Strippers, Nelson assembled in the grand sculpture court a stockpile of industrial and agricultural machinery, timber and metal gleaned from online auctions of company liquidations. Knitting machines, weighing scales, cement mixers, filing cabinets, drill bits, milling machines and tarpaulins were laid out, sometimes stacked, with the space partitioned using wood salvaged from a Victorian Ministry of Defence barracks and NHS hospital doors. The exhibition displayed with incongruous care the remains of what was once the apparatus of British productivity.

The days when the exhibition of non-art stuff in elite galleries might be considered challenging are long over, and part of the point of a show like The Asset Strippers is for visitors to recognize the art historical references, from Duchamp and Picabia through to Rauschenberg, Paolozzi, Caro, Serra and so on. Reviews of the exhibition took pleasure in detecting echoes of iconic artworks in the machines. In The Observer, for instance, Laura Cumming claimed that a compressed chunk of metal, perhaps some kind of boiler, steel-grey and truculent, exactly resembles Max Ernsts Celebes.

Objects of delight or utility. Beyond the art historically familiar, in The Asset Strippers Nelson taps into what is, by now, a generations-long embrace of saving apparently useless old stuff. Second-hand, retro, vintage, recycled, upcycled, preloved: the vocabulary used to describe the passionate preservation of remnants of the past has flourished along with the mainstream embrace of what used to be the preserve of a self-consciously recondite and culturally marginal sensibility. We live in the age of the patina. The wipe-clean surfaces of modernity hold no allure and no mysteries; instead, real value is to be found in the unbleached, grease-stained, sweat-burnished remains of the workshops and factories that built that world. The objects made in those factories have taken their place in antique shops, auction sites and flea markets, which is to be expected. What is perhaps novel about the current relation to the recent past is that it is not just the furniture, couture and nostalgic gewgaws of childhood that remain auratic objects of desire, but the machines and tools that turned them out and the overalls worn by the workers on the assembly lines, boiler rooms, ridges and furrows of past times.

What, in the end, is most confusing about The Asset Strippers is that, despite its overly signposted art historical and sociopolitical references, I still liked it. I liked it even though I disapproved of nearly everything about it. There appears to be something irresistibly attractive about old machinery even to the non-mechanically inclined. The colours, the branding, the complexity of the construction and the ingenuity of the design; the painterly surfaces produced by years of use and misuse; the much-heralded patina beloved by the vintage hound; the alien presence of a very heavy object that did and might still do something. The Asset Strippers is, at once, almost unbearably poignant and insufferably precious. The branded goods and trade names call forth a world of local entrepreneurship that, for a twenty-first-century audience, is probably more familiar to viewers of Wallace and Gromit than professionals in contemporary manufacturing. The stacking of the objects contributes in no small part to the invitation to wonder: it is not so much the way the makeshift plinths elevate the stuff in an ironic gesture towards their sculptural status in the gallery, but the fact that it is reminiscent of the kind of Spielberg magic capable of transforming the everyday by just shuffling the pieces. Were these immovable objects piled up by some poltergeist or extraterrestrial? They seem to have been effortlessly deposited or discovered, like the Second World War planes in Close Encounters

This is all part of the charm of The Asset Strippers, the way it flirts with sci-fi, collecting and hipster retail (in the promotional photos Nelson could be modelling for a Japanese menswear designer, all distressed vintage denim, knitted hat and salt-andpepper facial foliage). It is a work of seduction; it invites visitors to luxuriate in the presence of what we have learned to see as beautiful old things without complications. This is the postindustrial world, where everything that has been preloved or unloved or forgotten can be reloved, revived, repositioned as art, as a collectible, a piece. It is a world where factories and factory labour have been sent far away, out of sight and beyond the experience of consumers, so that big, dirty machines are so marvellous to behold that they must have come from another age or from Mars.

Where, though, are the asset strippers of the title? The artist has rescued the assets that have been stripped, but the sellers, not to mention the people for whom the assets were tools, remain absent. There is so much missing in The Asset Strippers. It is the absence of context that makes the retrieved remnants so compelling as things, as forms, and that also makes visible the decontextualizing violence of art galleries and museums. The missing factories, missing workers, missing products, missing bosses, as well as the missing noise and movement it is the missing economic and social history that might account for the invention, use and redundancy of all the objects gathered in the exhibition that Nelson manages, negatively, to invoke. In its summoning of the departed, absconded or unreachable, Nelsons exhibition taps into a common aspect of much recent cultural work: a preoccupation with ghosts.

The Asset Strippers speaks to the concerns of this book in a number of ways. It addresses a set of cultural preoccupations that have become familiar an obsession with the past that ranges from a profound sense of loss to an aestheticizing of the material remains of old things, big and small; a fascination with what is taken as the authenticity of old things, especially those related to labour and with production in particular; a sense that we are living amid the ruins or among the relics of a lost world; a foreshortened sense of the future and a fascination with so-called retro-futures, old versions of the future now positioned as missed opportunities; a sense of concealed, absent or inaccessible spaces and things.

The topics addressed here circle around a number of these issues, especially as they pertain to matters of space and time of temporality in its spatial extensions across the country and the city, and in its contested and reworked forms as public symbols or markers. A good deal of what follows is concerned with the stuff that is left behind the abandoned or discarded, used up, exhausted: the remains. And a fair amount of the cultural work discussed here is concerned with working among, and with, the remains the scraps, the edges, the wasted. Decommissioned military sites, post-industrial spaces, depopulated countryside, contested or forgotten zones between sites, monuments to forgotten heroes. Places where things once happened, never happened, might yet happen.