Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2018 by Janet R. Daly Bednarek

All rights reserved

First published 2018

e-book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.460.5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017963242

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.984.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

INTRODUCTION

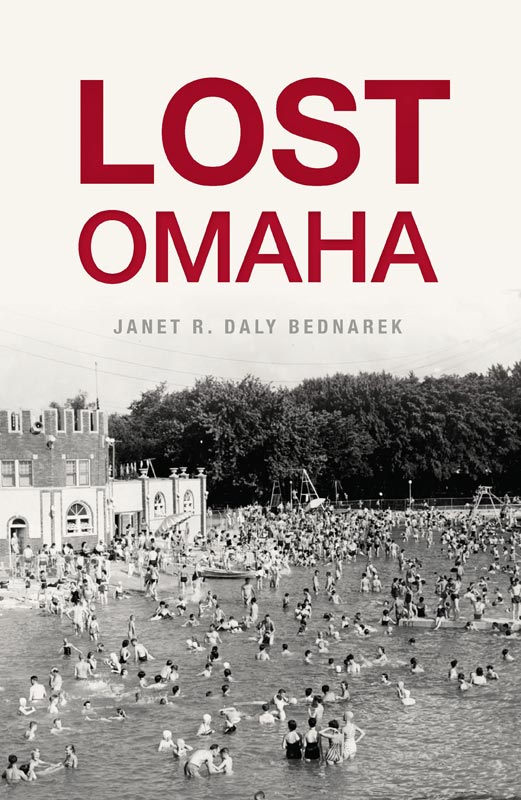

Creative destruction. This is a term coined by economist Joseph Schumpeter to describe the capitalist process in which the old is incessantly destroyed to make way for the new. Historian Max Page used the concept to inform his work The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 19001940, which focuses on the making and remaking of Fifth Avenue. And it is an idea that comes to mind when thinking about Omaha, especially since World War II. As the economy in Omaha transformed from one based largely on agriculture, food processing and railroads to one driven by insurance companies, universities, medical centers (eds and meds) and other service economy businesses and as automobile-enabled suburbanization changed where people lived and worked, the landscape of the old Omaha gave way to the new. And in creating that new landscape, much was gained, but much was also lost.

Omaha, as was the case with most U.S. cities, began the postwar period with a downtown that functioned as its singular vital center. People went downtown to shop, to visit the doctor, to do their banking and to be entertained. Civic organizations held their meetings downtown. And people went downtown to work. Omahas downtown skyline reflected these many activitiesfor example, the Medical Arts Building, the Hotel Fontenelle and the Omaha Athletic Club. A large warehouse and manufacturing districtlater dubbed Jobbers Canyonhugged the riverfront, as did a major lead refinery. Over time, however, the function of the downtown changed. Shops (particularly department stores), bank branches, movie theaters, jobs and professional offices moved to the suburbs, following residential populations. As these functions left the downtown, the buildings that housed them lost their clientele, indeed even their original reason for existing. Though many served as highly recognizable landmarks, eventually they gave way under the force of creative destruction.

Not everything that made Omaha the kind of city it was in 1945 existed in the downtown, however. To the south lay the sprawling Omaha Stockyards and the packing plants that employed thousands. To the west, many Omahans spent their leisure time at the Peony Park amusement park or the racetrack operated by the civic organization AK-SAR-BEN. Over time, however, these, too, felt the changes transforming how and where Omahans worked and played. Though perhaps the most visible of the creative destruction that transformed Omahas landscape centered in the downtown, these outlying landmarks also gave way to the forces of change.

However, they were not the first structures to give way to change. Omaha, founded in 1854, transformed from frontier outpost to city rapidly, ranking among the one hundred largest urban areas in the United States as early as 1870. Wood frame building gave way to brick and then to steel and concrete. By 1912, the city boasted of the tallest building between Chicago and the West Coast, the nineteen-story Woodman of the World Building. The settled area of the city spread north, west and south from the riverfront. Old replaced new with regularity as growth and progress remained deeply entrenched civic goals. Though occasionally some would make note of lost buildings and other landmarks, Omahans were not much for looking backward.

That changed, though, in the late twentieth century. From the 1950s through the 1970s, Omahas downtown experienced a very significant wave of creative destruction. And, perhaps because for the first time some Omahans began to challenge demolition in the name of progress, the landmarks lost in that wave have received a good deal of attention. The old Post Office Building, in particular, became a rallying cry for those who favored historic preservation over demolition. Construction on the old Post Office Building began in 1892 but was not completed until 1906. A local history notes that initially the John Latenserdesigned structure was destined to last one thousand years and would be an attraction to match the fabled castles of Europe.

This work focuses on a subsequent wave of creative destruction between the 1980s and the early twenty-first century. During those years, Omahas civic leaders worked to build on the changes they had spearheaded in the 1960s and 1970s and in many ways to complete the transformation to a new Omahaone in which the downtown would serve not as the center but as an important image center for the city: an Omaha known for telecommunications, insurance and health services, not brawny railroad and packinghouse workers. The Hotel Fontenelle and the Omaha Athletic Club felt the brunt of the changes that came to the downtown in the 1960s. As downtown lost its centrality and as social habits changed, both closed their doors by the 1970s. They had, however, survived the wave of demolition in the 1960s and 1970s. They, along with the Medical Arts Building, which held on to tenants a bit longer, would not survive a subsequent wave beginning in the late 1980s. Outside the downtown, Peony Park, which began as a way station, well out of town, along the old Lincoln Highway, closed as suburban sprawl prevented its expansion and changing leisure patterns took Omahans farther afield for their amusement park experiences. The AK-SAR-BEN racetrack and coliseum, challenged by other gambling and entertainment venues, gave way to First Data Resources, the expansion of the University of NebraskaOmaha and the creation of a new urbanist development. The stockyardswhich had lost major customers with the closures of the citys meatpacking plants in the late 1960s and early 1970sfinally closed in 1999, ending a long chapter in Omahas history. And another long history ended with the demolition and cleanup of the ASARCO lead refinery along the riverfront as Omahas leaders became more attuned to environmental concerns.

It is temptingespecially in a work titled Lost Omahato wax nostalgic about those urban landmarks that have disappeared since World War II. It is not difficult to mourn once vibrant and well-loved venues that are no more. At the same time, while it can be appropriate to hold on to memories of those places, we must also recognize that cities can, do and should changeand whether those changes are for the good or bad is often a matter of perspective. This is not to argue for the comprehensive sweeping away of the pastthe mind-set behind modernist architecture and much of the urban renewal program of the 1950s and 1960sbut memory can be a complicated thing. For example, while many may remember Peony Park for its dance bands and concerts, others will remember that its owners fought to keep its swimming pool segregated. The stockyards and packing plants provided thousands of jobs, but those jobs were often dirty and dangerous. And the yards and plants produced a tremendous amount of pollution. So did the ASARCO refinery, so much so that it resulted in the designation of much of eastern Omaha as a Superfund site. Omaha has held on to many buildings that help tell the story of its past, and it has lost others. But even when the buildings are gone, the story can still be told. Creative destruction may indeed result in demolition and replacement, but nothing is ever truly lost until it is forgotten.