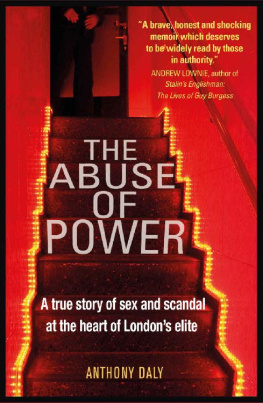

First published as Playland by Mirror Books in 2018

This edition published in 2019

Mirror Books is part of Reach plc

10 Lower Thames Street

London EC3R 6EN

England

www.mirrorbooks.co.uk

Anthony Daly

The rights of Anthony Daly to be identified as the author

of this book have been asserted, in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 978-1-912624-73-7

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior

written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Every effort has been made to fulfil requirements with regard to

reproducing copyright material. The author and publisher will be

glad to rectify any omissions at the earliest opportunity.

Cover image: Stephen Mulcahey, Alamy

In memory of John (Jackie) Duddy and

Bishop Edward Daly, two souls fused together

for eternity in a moment of violence.

And for Damie

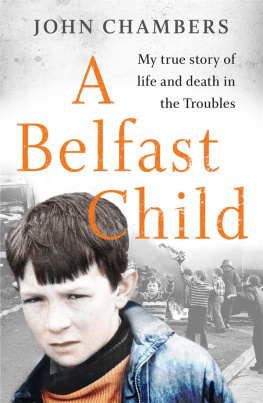

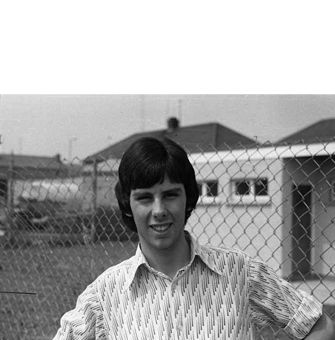

Feeling caged in: the author photographed near his home in Creggan Estate, Derry in February 1975, before he left for London.

Authors Note

In her memoir, Old Bloomsbury , Virginia Woolf lamented her failure to capture the conversations of the early Bloomsbury Group: Talk, even talk of this interest and importance is as elusive as smoke. It flies up the chimney and is gone. What I wanted to do in this memoir was to recapture some of the conversational smoke from my past; in the encounters I had, the discussions I listened to and the events I witnessed in 1975.

The fact is, storytelling is storytelling and both fictional and non-fictional storytelling use the same sorts of narrative devices: scene, description, exposition, reflection and voice. All literature is shaped by the writers imagination and consciousness. Although I have created and approximated dialogue that I cant recall word for word, I have tried to capture the emotional truth and the essence of my interactions with people as I remember them; to reveal the honest heart of the story. Writing dialogue served another purpose for me; I wanted to raise the dead, I wanted to hear their voices again.

Introduction

According to the Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel, its a mark of being human to want to forget. The Ancients saw it as a divine gift. Without forgetting, we would live in permanent paralysing fear of death. We are reminded of that fear at the extremes of human experience, particularly in the shadow of violence. This is why Id worked to forget, to keep my memories locked away. After all, how can we continue in our daily lives carrying the burden of the past at every step?

Id made sure that the person who went to London in 1975 no longer existed. Or so I thought.

Whether were conscious of it or not, the past lives on in us, and sooner or later were going to have to confront it. Its impossible to stop it catching up with us. It starts as a trickle seeping through the cracks and quickly becomes a torrent It hit me with full force in July 2014.

It was a bright Sunday morning in Derry and white clouds scudded overhead. Light was dappled by the trees as I walked the dog to get my morning paper. For many years now stories had seemed to appear almost weekly in the papers about people in authority sexually abusing children.

The floodgates were opened in Ireland in the early 1990s when Father Brendan Smyth pleaded guilty to the sexual assault of more than 140 children over a 40-year period. The Taoiseach Albert Reynolds subsequently resigned when it appeared the authorities had been protecting a child abuser in the church. Cases began to emerge of sexual and physical abuse in parishes across Ireland. It was impossible to avoid the television and newspaper coverage: it felt as if a collective exorcism was being performed on generations who had suffered in silence. My own demons were already becoming restless when further revelations emerged in 2010 about a church cover-up. I was prompted at that point to write a long letter to a retired bookseller in England, in the hope that I might get some answers about what had happened to me in the context of a much greater cover up, also from 1975. I did not receive an answer to my letter and let the matter sink again to the depths of my consciousness.

There was more to come, however, as the world of pop music and light entertainment had its own Father Brendan Smyth, whose name was Jimmy Savile. The revelations about this intelligent but profoundly maladjusted eccentric and serial abuser were followed by claims about other celebrities. The incredible courage of their survivors saw these abusers appear in the dock, at last. The situation became yet more unsettling for me. News reports started naming politicians, including some in their graves. But none of this had prepared me for the newspaper headline that confronted me as I entered the shop that summer morning.

The story on the front page of the Sunday Mirror named politicians who were allegedly involved in having sex with underage rent boys around the early to mid 1980s. My hands were shaking as I read the story. I could not know the truth of those claims, but I did know that some of the politicians named in the story were having sex with underage boys and young men several years earlier, in the mid 1970s. I knew because I was one of those young men.

Later that afternoon I read the article again. My mind was in turmoil and I felt physically sick with worry. I was in a state of shock. Everything that Id successfully buried for 40 years was in front of me, as if the abusive hands of the past had now reached into the present. I was having difficulty breathing. I went into the bathroom and splashed water on my face; the person staring back at me in the mirror was ashen.

I came back into the room and handed the paper to my wife. Read that, I said.

She looked at me quizzically and glanced down at the article.

Why did you want me to read this? she said distastefully a few minutes later.

I couldnt answer because I was crying, silently and uncontrollably. She looked over and at first thought I was putting it on. Joking. Then she saw the grief and she came to me. I stood up and she took me in her arms.

Whats wrong, what is it? I was still unable to speak.

I cried painfully for a long time. Finally, I told her I had been raped in London when I was 20 years old.

I pointed to the newspaper. I was involved in that, was all I could manage. I could tell her no more for now. I had to drip feed some of the horror over the next few weeks. She said no matter what had happened shed support me and would be there for me. She said the last time shed seen me cry like that was when our baby girl had died.

Over the next few days I started to have flashbacks and began to feel emotions Id not felt in years. Raw visceral fear. Intense shame. Burning anger. I had to tell someone: I could no longer keep this to myself. Strangely enough, the first person I could think of was a priest. I had enormous respect for Bishop Edward Daly and so did most of Derry. Hell be forever remembered in the iconic film footage of him waving a white handkerchief at advancing paratroopers, appealing for a truce as he tried to save the life of a mortally wounded friend of mine on Bloody Sunday. Bishop Daly was someone I felt I could confide in about my experiences in London in 1975, and I wanted his advice. So I met him and told my story while he listened patiently.